The .NET Journey: Recapping the last year

Having just completed Connect(); // 2015, we thought to take a moment to review everything that’s happened with .NET over the last year, between last year’s and this year’s Connect();. And what a year it’s been! We’ve seen significant developments in the .NET Framework, including the release of new versions, and also the release of two new technologies, .NET Native and .NET Core, both of which will change the ways in which the .NET Framework is used and the platforms on which it is supported.

The .NET Framework 4.6

The .NET Framework version 4.6 was released in July with Visual Studio 2015 and is automatically installed on all Windows 10 systems. As the latest release of a mature product known for its robustness and ease of development, .NET Framework 4.6 offers improved app performance and a variety of individual feature enhancements:

- A new version of the 64-bit JIT (Just-in-Time) compiler significantly enhances performance and supports SIMD hardware acceleration. A compiled app that targets x64 or anyCPU automatically takes advantage of the new JIT compiler when it runs on a 64-bit operating system.

- Improved loading of assemblies decrease virtual memory.

- Greater control over the garbage collector lets you disallow garbage collection during the execution of a critical path by calling GC.TryStartNoGCRegion and EndNoGCRegion. You can also use an overload of the GC.Collect method to control whether both the small object heap and the large object heap are swept and compacted or swept only.

- The addition of SIMD-enabled vector types, such as Vector2, Vector3, and Vector4, Matrix3x2, and Matrix4x4, to the System.Numerics namespace.

- Support for the Windows CNG cryptography APIs. The .NET Framework 4.6 adds the RSACng class to provide a CNG implementation of the RSA algorithm, a set of extension methods for X509 certificates, and enhancements to the RSA API so that common operations no longer require casting or type conversion.

- Methods to convert the .NET Framework’s DateTimeOffset values to Unix time.

- An AppContext class, which allows library developers to provide a uniform way for users of their application to opt out of new features.

- Task-based asynchronous pattern (TAP) enhancements, including convenience methods to return completed tasks in a particular state (such as Task.FromCanceled) and a new class, AsyncLocal<T>, that allows you to store ambient data that is local to a particular asynchronous control flow. In addition, for apps that target the .NET Framework 4.6, tasks inherit the culture of the calling thread.

- Improved rendering in Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) and Windows Forms. WPF also has improved support for touch.

- In Windows Communications Foundation (WCF), support for TLS 1.1 and TLS 1.2 in addition to SSL 3.0 and TLS 1.0. You can also select the protocol to use, or disable less secure protocols, programmatically, and you can send messages using different HTTP connections.

There are also enhancements in networking, Windows Workflow Foundation (WWF), transaction processing, and code page encoding. For a complete list of new features and additional detail, see What’s New in the .NET Framework.

The .NET Framework 4.6.1

The .NET Framework version 4.6.1 was released on November 30 and is automatically installed with the Windows 10 November Update. The .NET Framework 4.6.1 features performance and reliability improvements, as well as a handful of new features. As part of the ongoing work to modernize the cryptography API, the .NET Framework’s cryptography API now includes support for Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) X509 certificates. In addition, Windows Presentation Foundation features spell-checking improvements and additional support for per-user custom dictionaries, while Windows Workflow Foundation now supports a distributed transaction manager other than MSDTC.

In-place and side-by-side upgrades

The .NET Framework 4.6 or 4.6.1 is an in-place upgrades for the .NET Framework versions 4.0, 4.5, 4.5.1, and 4.5.2. In other words, if any of those other four versions are already installed on a system, installing the .NET Framework 4.6 or 4.6.1 replaces them.

The .NET Framework 4.6 or 4.6.1 is a side-by-side upgrade for systems with any versions earlier than the .NET Framework 4 (the .NET Framework versions 1.1, 2.0, or 3.5); in other words, the .NET Framework does not replace these versions but instead is installed separately. Applications that target these older versions of the .NET Framework run on the older version if it is present. If the original targeted version of the .NET Framework is not present, they can instead run on the .NET Framework 4.6 if the following entry is made in the app’s configuration file:

<configuration>

<startup>

<supportedRuntimeversion=“v4.0“ />

</startup>

</configuration>

Application compatibility with .NET Framework 4.6 and 4.6.1

Will an application developed for an earlier version of the .NET Framework run under the .NET Framework 4.6 or 4.6.1? The .NET Framework maintains an extremely high level of backward compatibility from one version to another. Almost all applications that target the .NET Framework 4 and its point releases will run without modification on the .NET Framework 4.6 or 4.6.1. For a list of changes that may require recompilation, along with an assessment of their significance and possible workarounds, see Runtime Changes in the .NET Framework 4.6 and Runtime Changes in the .NET Framework 4.6.1. Some changes only affect apps that explicitly target the .NET Framework 4.6 or 4.6.1, but provide a different behavior for apps that target a previous version; for a list of these, see Retargeting Changes in the .NET Framework 4.6 and Retargeting Changes in the .NET Framework 4.6.1.

.NET Native

.NET Native is a compilation and deployment technology for Universal Windows Platform (UWP) apps written in C# and Visual Basic. It uses and optimized implementation of .NET Core (discussed in the next section) and compiles apps to native code. In other words, it compiles an app running on an ARM system to the ARM instruction set, and it compiles an app running on an x64 system to the x64 instruction set. This differs from most .NET Framework applications, which are compiled to intermediate language (IL) before they are deployed, and then are compiled to native code at runtime by the Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler.

.NET Native produces small, compact binaries that load and start up quickly. It statically links only those code elements from the .NET Framework Class Library and any other libraries you may use. Code paths that are not executed by your application are not linked into the binary. Along with your application code, .NET Native produces a small app-local runtime whose primary responsibility is memory management and garbage collection. For more information on .NET Native’s compilation technology, see .NET Native and Compilation.

Normally, the .NET Framework Class Library includes rich metadata about each assembly, type, and member. When compiling apps to native code, however, .NET Native includes only the metadata that an app actually needs at runtime. For some reflection and serialization scenarios, the .NET Native tool chain may be unable to detect that it needs specific metadata. You can identify these scenarios and ensure that the .NET Native tool chain includes all the necessary metadata at runtime by testing the release version of your app and defining the required metadata in a runtime directives file. In addition, two troubleshooters that help supply the runtime directives needed to reflect on or serialize types and type members are available.

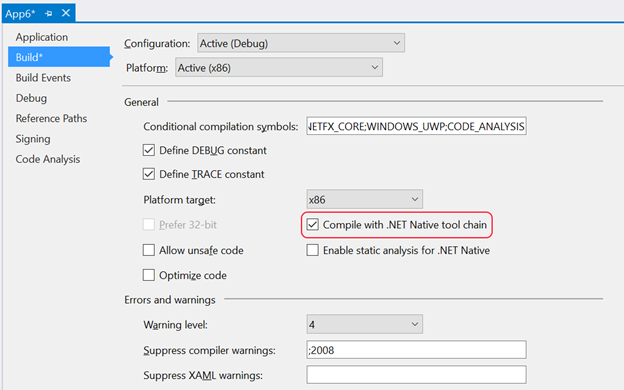

By default, the release builds of all UWP apps written in C# or Visual Basic are compiled to native code with the .NET Native tool chain. For faster compilation and ease of debugging, however, debug builds are not compiled with the .NET Native tool chain. This makes it important to thoroughly test the release builds of your app on each of its target platforms.

For more information about creating UWP apps that are compiled to native code, see Getting Started with .NET Native.

.NET Core

.NET Core is a modular, cross-platform, open source implementation of the .NET Framework that will run on Windows devices, as well as on Linux and Mac OSX. Unlike the .NET Framework, .NET Core consists of a set of runtime, library, and compiler components that can be used in various configurations, depending on the needs of your application.

To get a better sense of what .NET Core is, let’s compare it to the.NET Framework 4.6:

|

.NET Framework |

.NET Core |

|

A sizable runtime, the CLR, that provides memory management and a host of other application services. |

CoreCLR, lightweight runtime that provides basic services, particularly automatic memory management and garbage collection, to your app, along with a basic type library. |

|

The .NET Framework Class Library, a large, monolithic library with thousands of classes and many thousands of members. Whether or not your application uses individual types and their members, they are always present and accessible. |

CoreFX, a set of individual modular assemblies that you can add to your application as needed. Unlike the .NET Framework 4.5, where the entire .NET Framework Class Library is present, you can select only the assemblies that you need. That the assemblies are local to your application solves versioning problems and reduces the overall size of your applications. For example, if you are developing a vector-based application, you can download the System.Numerics.Vectors package without the overhead of a large class library. |

|

Suitable for developing traditional Windows desktop applications. |

Suitable for a full range of modern applications that operate on small devices with constrained memory and storage. |

Aside from a basic setup procedure, each CoreFx module is independently downloadable as a NuGet package from the CoreCLR GitHub repo.

For more information on .NET Core, see Introducing .NET Core. For the basic .NET Core documentation set, see .NET Core: A General Purpose Managed Framework.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this recap of everything that’s happened in .NET over the last year. As always, we invite your feedback, suggestions, thoughts, and ideas on UserVoice, through the in-product feedback UI, or file a bug through the Visual Studio Connect site.

|

|

Ron Petrusha is a programming writer on the .NET Framework team. He is also the author or co-author of a number of computer books, including Inside the Windows 95 Registry, VBScript in a Nutshell, and Visual Basic 2005: The Complete Reference. |

Light

Light Dark

Dark

0 comments