Recursive Descent Formula Parsing in C# in .NET

Intrinsic to any script-based application is the notion of parsing. In CloudSheet, described in detail in the forthcoming TED Case Study entitled “Massively Scalable Graph-Based Computation in Azure,” a formula parser tokenizes arbitrarily complex Excel-like formulas making subsequent evaluation faster and more efficient. This paper will cover the parsing component.1

Overview of the Solution

The objective of the parser is to tokenize arbitrarily complex formulas of differing types to enable rapid and accurate evaluation. Example formulas include:

=1+3

=sum(a1:a3)

=sum(a1:a3,5)+pi()/2

=pmt(a1/12,(a2*36),b5)

=stock(ibm)*a5+stock(msft)*a6

=concatenate(“test”,b12)

=data(sheetcsvssample.op)

=select(a5,3,2,5)

And so on. As can be seen, formulas can return either numeric or string-based results, concatenation being an example of the latter. The current implementation supports around 47 numeric functions and 10 string functions (a subset of current Excel functionality), although more are being added as needed.

The parser, which is contained within the “Cell” grain (actor) in CloudSheet, is passed a text string from the client (either typed in by a user or loaded from a file). After tokenizing, the tokens are passed to the evaluator, which calculates a response. As the model is recalculated, the evaluator is called to update its result based on potentially new data. The parser is only invoked when the input formula is changed; the evaluator is called on every recalculation where necessary (i.e., in which a predecessor value is updated).

Implementation

The implementation chosen is a recursive-descent parser.2 The parsing method is invoked with two arguments:

private void Parse(List<Formentry> numStack, List<Formentry> opStack)

{

while (this.index < this.txt.Length)

{

Formentry tok = GetToken();

...

}

The arguments are the number stack and the operator stack. The former holds formula arguments, the latter holds formula operators, such as arithmetic operators or functions.

The act of tokenizing creates a data structure called a “Formentry” (formula entry) which describes the token. The various types of tokens are enumerated below:

public enum TokenTypes

{

UNDEFINED=-1,

NUMBER = 0,

CELLREF = 1,

OPERATOR = 2,

NAME = 3,

RANGE = 4,

SUBSTRING = 5,

FUNCTION = 6,

UNARY = 7,

PRECEDENCE = 8,

DATE=9,

ARGSEP=10,

LPAREN=11,

RPAREN=12,

FUNC = 13,

COMPARISON = 14,

RESOLVEDRANGE=15,

STRINGFUNCTION=16,

STARTPARSE=98,

ENDPARSE = 99

}

Note that a Formentry can describe either arguments or operators. Some descriptions follow:

- CELLREF indicates that the token refers to another cell. Cells referred to in this way are predecessors to the current cell; the current cell is thus a successor to the referred-to cell. As predecessors change, the recalculation method in this cell is invoked to get the most recent value of the referred-to cell(s).

- ARGSEP indicates a separator between arguments in a formula – the comma in

=sum(3,4)for example. - LPAREN and RPAREN indicate parentheses and thus subexpressions (and thus recursion, as will be described below)

- NUMBERs are always maintained internally in double-precision format even if they are input as integers, in order to have a common format for operations, to avoid casts. The client is responsible for presentation formatting.

- A FUNCTION is a numeric function returning a double-precision value; a STRINGFUNCTION returns a string.

The GetToken() method is the lexer. It converts a text element into a token, represented by a Formentry. Here is an excerpt:

/* unary operators have the highest precedence */

if ((unary = ScanForUnary()) != -1)

{

f.tokentype = TokenTypes.UNARY;

f.value = unary;

this.index++;

return f;

}

/* logical comparison operators (=, <, >, etc) */

if ((comp = ScanForComparison()) != -1)

{

f.tokentype = TokenTypes.COMPARISON;

f.value = comp;

this.index++;

return f;

}

The lexer calls various worker subroutines (here it checks for unary operators and comparison operators) sequentially to determine the type of token, and returns it to the main parsing routine. This makes it trivial to add new types of lexemes, or tokens. (The _index global variable points to the current location in the input string. The lexer is responsible for ensuring that it always points to the next character after the detected lexeme.)

A parenthesis indicates a subexpression, and thus needs recursion. When this circumstance is detected, new instances of the number stack and operator are created and the parser invokes itself against the subexpression. For example, when a function is detected, a new level of precedence (recursion) is created:

if (tok.tokentype == TokenTypes.FUNCTION)

{

this.expectingvalue = true;

Formentry f = Push(numStack, opStack);

f.tokentype = TokenTypes.FUNCTION;

f.func = (int)tok.value;

Parse(f.newnumstack, f.newopstack);

this.expectingvalue = false;

continue;

}

Note the push() function which:

- Creates a special PRECEDENCE Formentry

- Creates new instances of the number stack and operator stack

- Increases the stack depth

- Creates a STARTPARSE Formentry on the new stack

- Creates and returns the first token Formentry on the new stack

A corresponding pop() function also exists.

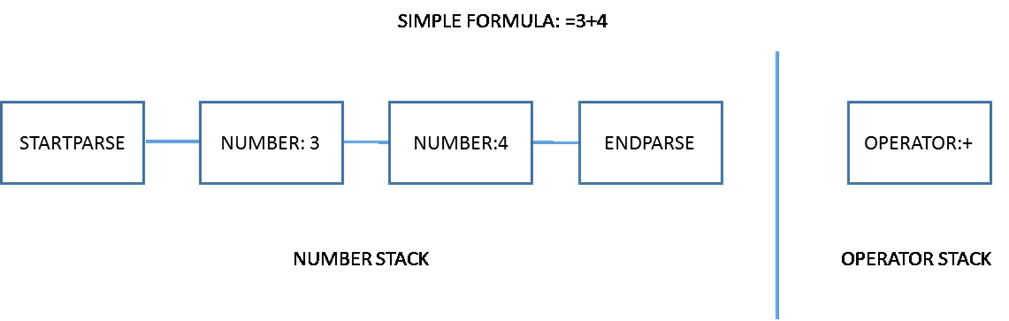

At the end of parsing, a set of data structures holding the tokens and their relationships to one another is created and presented to the evaluator. Here is an example of the result of a simple parsing session:

Each box indicates a formentry. The STARTPARSE and ENDPARSE Formentries are convenience structures which optimize the evaluation process. In this case, there is obviously no recursion.3

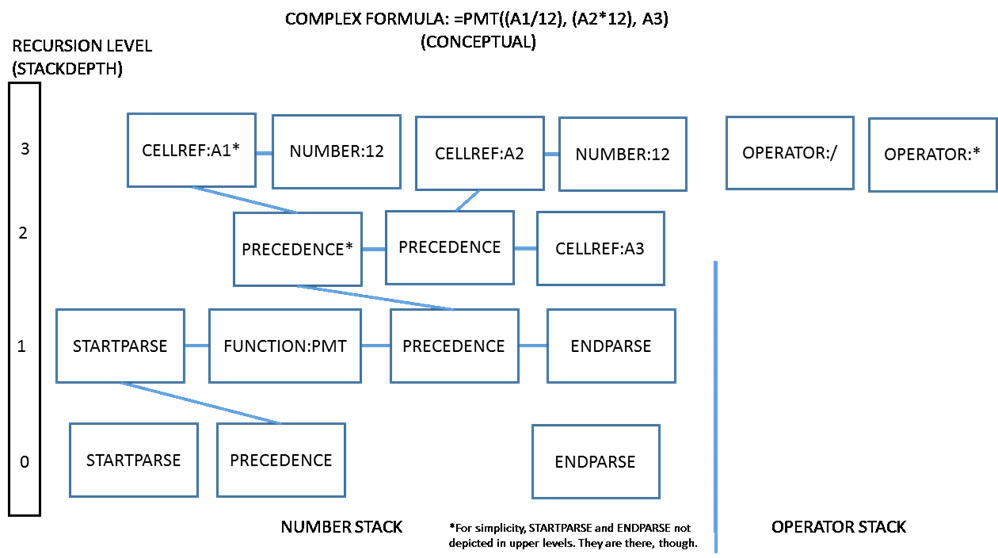

A more complex example is depicted below:

Here, multiple levels of recursion are shown. Each instance of a PRECEDENCE Formentry indicates a subexpression. At evaluation time, a depth-first traversal of the tree occurs such that as evaluation progresses, the deepest subexpression is evaluated (here: A1/12), then the next-deepest, and so on. The parser supports an arbitrary level of depth and complexity.

Challenges

Of course, what is difficult in any general purpose parser with a relatively open syntax is accounting for every possible case. A formula like =pmt((a1/12),(a230),a3) is quite easy to parse as the precedence is made explicit by the existence of parentheses, while an equally valid version (far more popular with users because of its intuitiveness) exists: =pmt(a1/12, a230, a3). Here the ARGSEP (comma) signals that backtracing must be used to reparse the now-delimited expression.

In addition, with all the recursion, keeping track of all the levels of precedence can be challenging. A variable stackdepth has been of immense help in debugging issues here. If at the end of a parse stackdepth is not zero, it is likely that due to a recursion problem.

Opportunities for Reuse

The parser can be reused in other contexts requiring parsing and evaluation (which was not covered here) of formulas using Excel semantics and syntax.

A command-line version of the parser (useful for debugging) is kept at https://github.com/barrybriggs/Parser .

1 Leaving the evaluator as “an exercise to the reader.” There, I’ve always wanted to say that in a technical document.

2 The curious reader is directed to the classic work on compilers: Alfred Aho, Ravi Sethi, and Jeffrey D. Ullman, Compilers: Principles, Techniques and Tools; Addison-Wesley. I have the 1988 edition. A slightly simpler explanation can be found here: http://www.engr.mun.ca/~theo/Misc/exp_parsing.htm.

3 I trust readers will forgive the crudity of these diagrams. Perhaps we need a sort of “Feynmann diagram” for recursive data structures.

Light

Light Dark

Dark

0 comments