Xamarin (and before that, Mono) allowed .NET code to run on multiple platforms for years. These days, there’s a new push in cross-platform with .NET Core and .NET Standard. This post looks at the history of code sharing in .NET and where cross-platform .NET is going with Core and Standard.

History of .NET Standard

In the early days of the .NET framework, there was little need to share code between applications. When Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) was released in 2006, it was a choice between WinForms or WPF, and developers didn’t have to support the same application in both frameworks. Though sharing files was sometimes needed between client and server apps, it was infrequent.

Microsoft then released Silverlight, a smaller, portable framework on Windows, Mac OS, and Linux. Suddenly, developers were asked to code two versions of the same application: a full-featured version made in WPF to only run in Windows and a smaller version that ran cross-platform in Silverlight. The Silverlight plugin was able to run these apps outside of the browser (OOB) which made it possible to build cross-platform applications. There was even some hope that Silverlight would eventually run on mobile phones. Though this never came to be, the need to have the same code run on multiple platforms became more crucial and more complex.

Add As Link

To add a class to both a Windows Presentation Foundation and a Silverlight application, one would have to Add As Link. To do this in Visual Studio, add the actual file to one of the two applications. For example, here’s how to add it to WPF:

- Right-click on the other project.

- Select Add Existing Item (Will open the corresponding dialog.)

- Navigate to the location of the original file and select it.

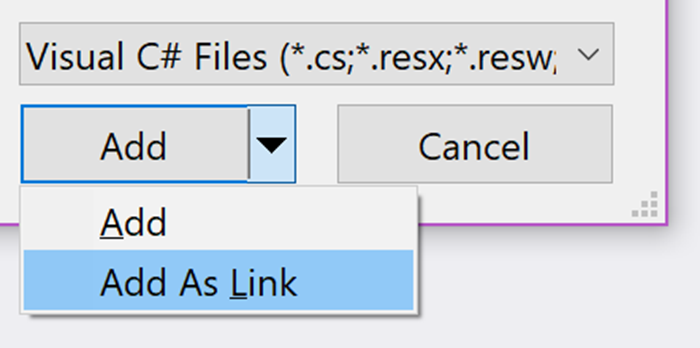

- Open the combo box located in the Add button.

- Then Add As Link (Creates a shortcut to the original file.)

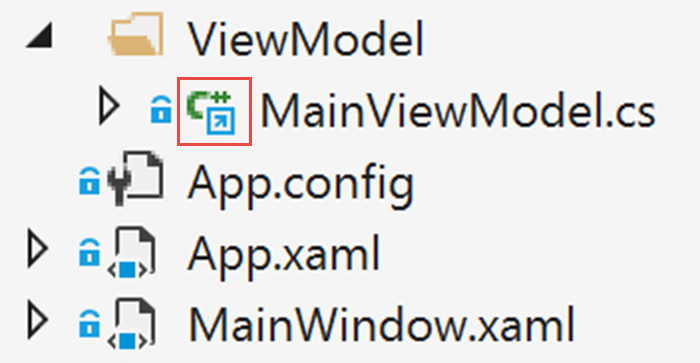

After the file has been added as a link, it shows up in the Solution Explorer with a small blue arrow. If you browse to the folder, you’ll see the file is not physically present. Visual Studio added a Link item to the project file, for instance:

ViewModel\MainViewModel.cs

Today, Add As Link still has utility, as when sharing images between applications. In Xamarin.Forms, you have the possibility to create a project using a Shared Project to share your source files. Under the cover, Visual Studio is using the same shortcuts shown above.

Portable Class Libraries (PCL)

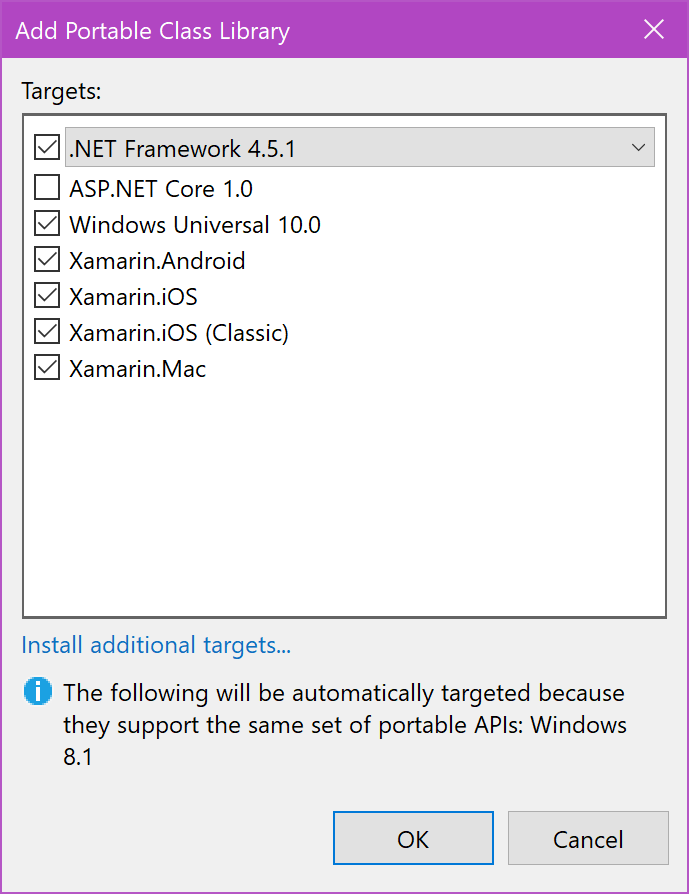

The maintenance of shared files can be challenging. Every time a new class is added, links to that file also need to be added to every application. With that in mind, in 2011 Microsoft released a new type of class libraries called Portable Class Libraries. A project type that creates a binary file compatible with multiple frameworks.

The available APIs are reduced each time a new target framework is selected. For example, if a class is available in .NET Framework 4.5.1 but not in Windows Universal 10.0, it won’t be available in the PCL targeting both these frameworks. The combinations of the target frameworks is called a Profile.

While PCLs were a breakthrough at the time of their creation, it was sometimes difficult to find information on which APIs were available and where to find them. In time, it became clear to the .NET team that a simpler approach was needed.

The Birth of .NET Core

.NET Core is an implementation of .NET running on various platforms, including Windows, Mac OS, and Linux. It was developed openly on Github by the Microsoft .NET team and external contributors. The first version was used to implement ASP.NET Core, a revamped version of ASP.NET running on Linux or Windows.

Executing .NET code on Linux or Mac OS is great, but we already have cross-platform implementations of .NET, such as Xamarin. Ideally, .NET libraries created for ASP.NET Core would also run seamlessly on these other platforms. As in Portable Class Libraries, this brings a well-known issue to light: how do developers know which APIs are supported on which platform?

A Specification: .NET Standard

In PCLs, the problem was solved by creating profiles. However, this led to a situation where developers couldn’t easily find out which APIs were available to them. Documenting the profiles was challenging and there were too many to keep track of.

The solution was to create a specification that would state which APIs were supported in which version of the specification. Each version of the specification would be backward compatible with the previous versions.

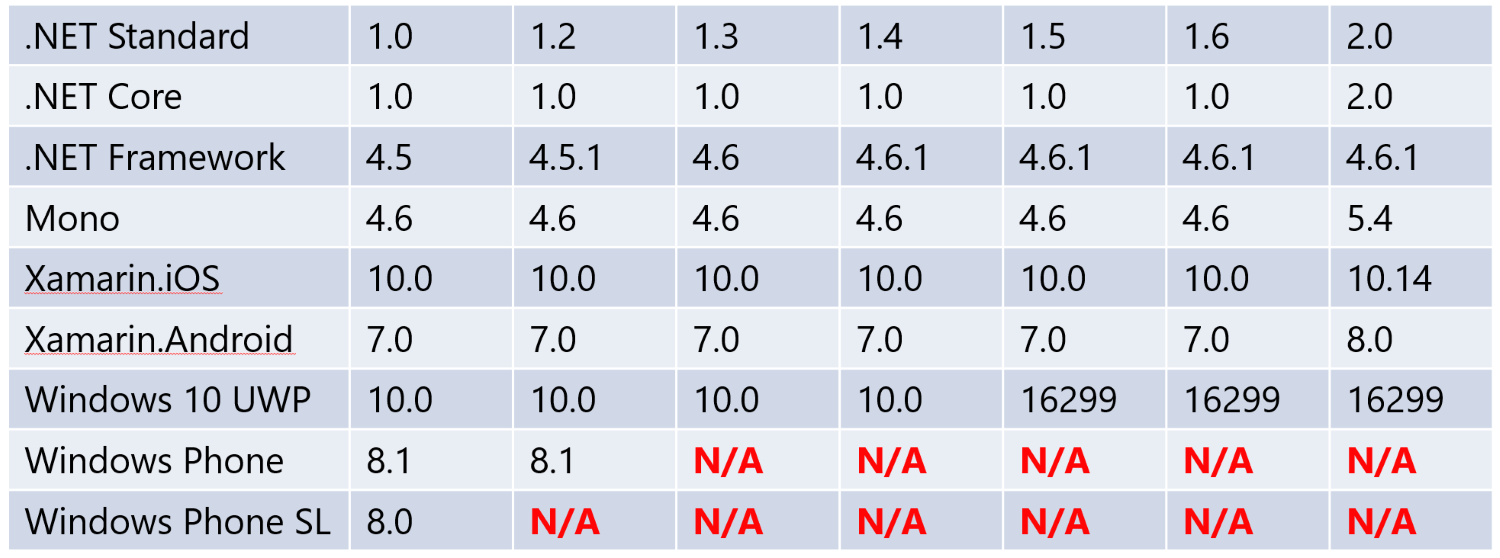

This specification can seem more complex than it actually is, so let’s look at an example of it in action. There’s a full compatibility table on the .NET Standard website. Here’s an extract of that table:

Decoding the Extract

The table can be decoded as follows: an Android application developed with V7.0 of the Xamarin.Android SDK will support references to class libraries developed with up to V1.6 of .NET Standard. However, you will need to upgrade your Xamarin.Android to V8.0 if you want to add a reference to a class library developed with V2.0 of .NET Standard.

In practice, it makes a difference because V2.0 of .NET Standard includes many more APIs than V1.6 (about 20,000 additional APIs!). Fewer Android devices support V8.0 than V7.0, so there’s also a tradeoff: access to more APIs or to more devices.

A good rule of thumb is:

- Application developers: Target the highest possible version of .NET Standard. This will give your application more APIs and make it compatible with more libraries.

- Libraries developers: Target the lowest possible version of .NET Standard. Which will make your library compatible with more applications, but you will have fewer APIs at your disposal.

For example, the MVVM Light Toolkit was recently converted to .NET Standard V1.0, meaning that MVVM Light is compatible even with .NET Framework 4.5 (older WPF applications). While this may sound unnecessary, it gives significant flexibility to developers who want to use the .NET Standard version without having to upgrade their pool of machines to a newer version of .NET.

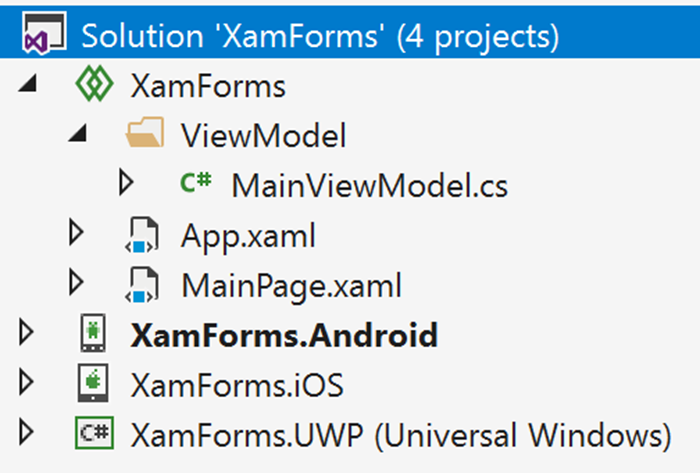

Xamarin Cross-Platform Applications

When you create a new Xamarin.Forms application in Visual Studio 2017, you have .NET Standard as a choice for the Code Sharing Strategy. In fact, Portable Class Libraries in Visual Studio 2017 are marked as legacy, marking a clear indication that you should gradually move away from PCL and on to .NET Standard.

Conclusion

In the long story of cross-platform compatibility, .NET Standard is a great new chapter. Portable Class Libraries were a real innovation in their time, but they also brought along some confusion, which .NET Standard has since clarified. At the same time, the additional compatibility with platforms, such as Linux, is a really exciting opportunity, especially for a web application.

Here’s a sample of a .NET Core console application using MVVM Light’s SimpleIOC, with instructions to run it on Windows and Ubuntu.

With Xamarin embracing .NET Standard, it’s now time to take a good look at these old PCLs and start converting them to .NET Standard.