(Note: Today’s article is written by guest scripter, Thomas Lee. Here is Thomas’ scripting autobiography from The Official Scripting Guys Forum! where he is a moderator: I’ve been scripting pretty much forever. I used to be pretty hot at JCL on the IBM 360 in the late 1960s, did a ton of shell scripting in the 70s on ICL VME. I learned batch scripting with DOS 2.0. I never really grokked VBS (and never got infected with *ix). But I truly “got” Monad when I first saw it in September 2003 and never looked back. I’m proficient in Windows PowerShell 1.0 and 2.0, and specialize in the .NET and WMI aspects. My one interesting fact is that I was the first person to blog about Monad. Check out my Under the Stairs blog and my PowerShell Scripts blog.

Part 1 is today. Part 2 will be published tomorrow. Thanks, Thomas!)

———-

One of the many challenges IT pros face in managing their systems is getting information out of a computer system. Sometimes, you just want a number, such as how many e-mail messages are in the queue, or how much memory a particular server is using. When it’s simple, you don’t mind too much if the output is not particularly pretty.

But then there are the times you need nicely formatted output that can be read easily on paper or on the screen. You want currency to be presented as currency, not as a decimal number with some random number of digits. Or you want a number expressed as a percentage. In those cases, formatting matters.

Among Windows PowerShell many virtues is its ability to get simple output simply. But when you need more control over your output, you can get that too. Pithiness when you want it, richness when you need it. Some of the formatting power comes from Windows PowerShell, and some is built-in to the Microsoft .NET Framework.

In this article, I first look at the basics of getting output and Windows PowerShell’s default formatting followed by a look at the Format-* cmdlets (and a few more). We then demonstrate how you can leverage the .NET Framework string-handling features before finishing off with using hash tables to get nicer output. As you read this article, why not open a Windows PowerShell window and type along as you read?

Formatting by Default

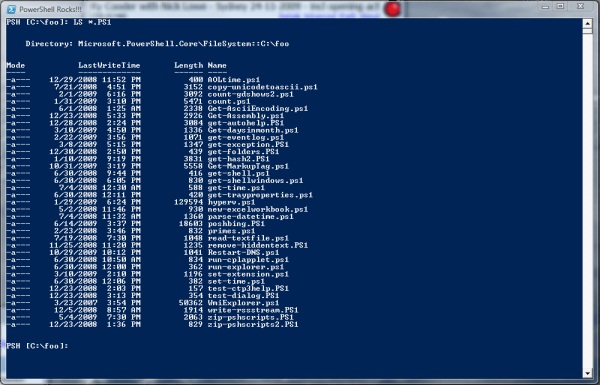

Most cmdlets produce objects of some sort. For example, in the Windows PowerShell console, type:

LS

As you can see in the following image, you get a nice listing of your current directory. Although you can’t see it, the cmdlet actually produces a set of objects that Windows PowerShell formats so that you get output without having to do all the convoluted programming that VBScript users love.

OK, so LS is really an alias of the Get-ChildItem cmdlet, but when issued against the file store provider, it still produces these object types that Windows PowerShell formats into a nice neat table. So how does the output end up looking like the directory listing we are used to?

The answer is simple: By default Windows PowerShell performs formatting of all the objects left in the pipeline (or the result of running a single cmdlet). The mechanism by which this happens is less simple but the basics are straightforward.

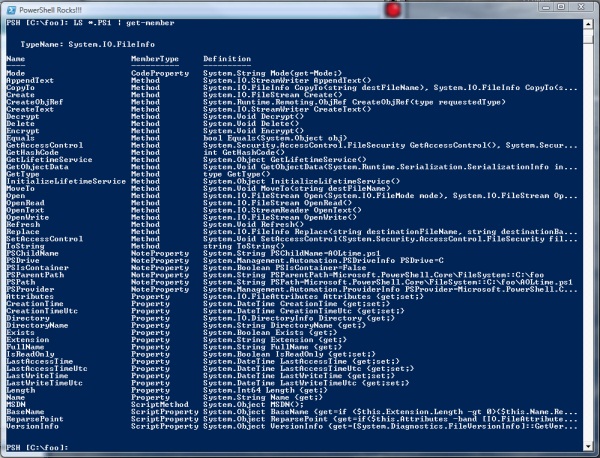

Cmdlets typically leave something in the pipeline. You can demonstrate this by running some arbitrary Windows PowerShell cmdlet or script, and piping it to Get-Member. In the following image, you can see the object types that were produced.

When Windows PowerShell finds objects that are ‘left over’, it just passes them to Out-Host. And Out-Host does one of two things: For most objects, it makes a call to either Format-Table or Format-List to create output. You can see this behavior by typing:

ls | Format-Table

As you can see if you try this, you get the same output as shown earlier (without having to pipe the output to Format-Table). Windows PowerShell chooses whether to call Format-Table or Format-List based on the number of properties that are to be displayed. By default, if the number of properties that the object contains is five or more, Windows PowerShell calls Format-List; otherwise, it calls Format-Table. The decision about which properties to display for a given object type is based on a set of PS1XML files. These XML files are installed by default, but naturally, you can override or extend them with ease to suit your needs. You can find more details about these files from within Windows PowerShell (Get-Help about_Format.ps1xml), and you can find the files themselves in C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell.

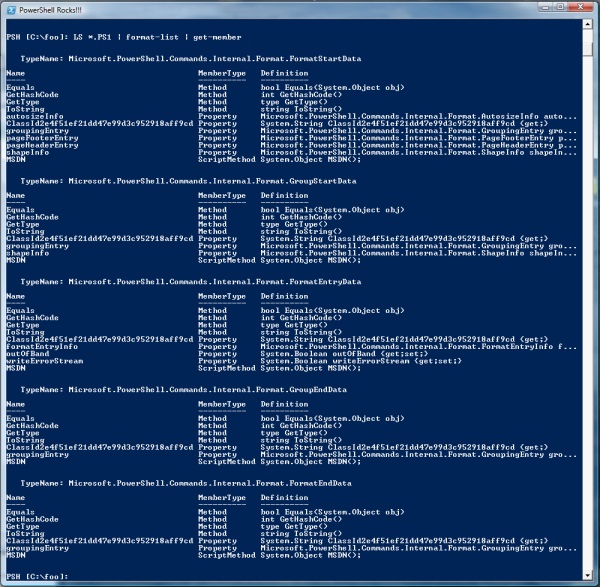

There are a few exceptions to this approach. The output of the Format-* cmdlets is such that Out-Default can produce output directly. The Format-Table and Format-List cmdlets produce a set of Microsoft.PowerShell.Comands.Internal.Format.* objects (as you can see in in the following image), and Out-Default is smart enough to know when to call a formatting cmdlet and when to send the output directly to the console.

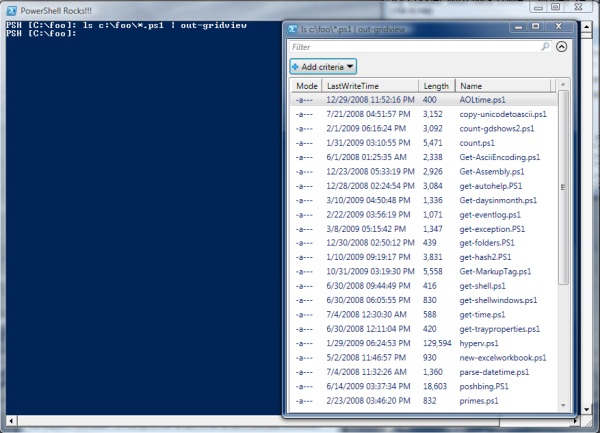

This means that if you put one of the Format-* cmdlets at the end of a pipeline, you can override the defaults specified in the PS1XML files. And of course, there are some other output methods you can use. For example Out-GridView takes the objects left in the pipeline and formats them into a nice window, which you can see in the following image.

This formatting scheme enables you to print by default, or to have total control over what Windows PowerShell outputs. You can specify the properties to display and a whole lot more as we shall see.

Format-List and Format-Table

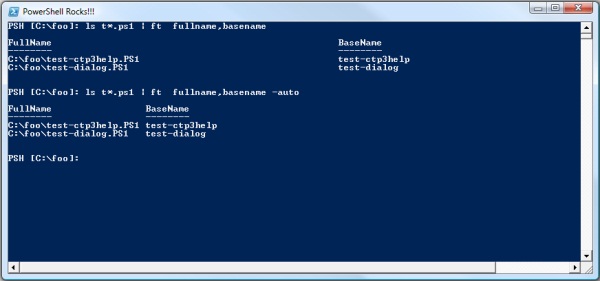

The two key cmdlets you use to display output on the screen are Format-List and Format-Table. They are very similar commands in structure. Format-Table creates a table with a set of columns, each with a column header. By default, the width of each column is determined by the size of what is being output (a file name, a count, etc). This sometimes results in very wide columns. You can use the -AutoSize parameter to get column widths as large as needed, which you can see in the following image.

Both Format-List and Format-Table take the names of the properties of the objects in the pipeline to determine what to output. As you can see in the previous image, I’ve used just the FullName and BaseName (the name without both the folder and file type) of the files I’ve selected.

For any given object type, you can discover the properties available to you and what they represent by looking in the MSDN Library. Just search for the object’s full name and usually the first result is what you want. Looking for System.IO.Fileinfo, the class is defined at http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/system.io.fileinfo.aspx. The MSDN Library is mainly aimed at developers, but if you are an experienced IT pro, you should be able to get what you need. Additionally, I’ve been slowly adding Windows PowerShell script samples to illustrate how to use a class. At the bottom of the System.IO.FileInfo page, you’ll see a short Windows PowerShell script demonstrating this object type.

See you tomorrow for Part 2!

0 comments