Today we are excited to announce the beta release of TypeScript 4.5!

To get started using the beta, you can get it through NuGet, or use npm with the following command:

npm install typescript@beta

You can also get editor support by

- Downloading for Visual Studio 2019/2017

- Following directions for Visual Studio Code and Sublime Text 3.

Some major highlights of TypeScript 4.5 are:

- ECMAScript Module Support in Node.js

- Supporting

libfromnode_modules - Template String Types as Discriminants

--module es2022- Tail-Recursion Elimination on Conditional Types

- Disabling Import Elision

typeModifiers on Import Names- Private Field Presence Checks

- Import Assertions

- Faster Load Time with

realPathSync.native - Snippet Completions for JSX Attributes

- Better Editor Support for Unresolved Types

- Breaking Changes

ECMAScript Module Support in Node.js

For the last few years, Node.js has been working to support running ECMAScript modules (ESM). This has been a very difficult feature to support, since the foundation of the Node.js ecosystem is built on a different module system called CommonJS (CJS). Interoperating between the two brings large challenges, with many new features to juggle; however, support for ESM in Node.js is now largely implemented in Node.js 12 and later, and the dust has begun to settle.

That’s why TypeScript 4.5 brings two new module settings: node12 and nodenext.

{

"compilerOptions": {

"module": "nodenext",

}

}

These new modes bring a few high-level features which we’ll explore here.

type in package.json and New Extensions

Node.js supports a new setting in package.json called type. "type" can be set to either "module" or "commonjs".

{

"name": "my-package",

"type": "module",

"//": "...",

"dependencies": {

}

}

This setting controls whether .js files are interpreted as ES modules or CommonJS modules, and defaults to CommonJS when not set. When a file is considered an ES module, a few different rules come into play compared to CommonJS:

import/exportstatements (and top-levelawaitinnodenext) can be used- relative import paths need full extensions (we have to write

import "./foo.js"instead ofimport "./foo") - imports might resolve differently from dependencies in

node_modules - certain global-like values like

require()andprocesscannot be used directly - CommonJS modules get imported under certain special rules

We’ll come back to some of these.

To overlay the way TypeScript works in this system, .ts and .tsx files now work the same way. When TypeScript finds a .ts, .tsx, .js, or .jsx file, it will walk up looking for a package.json to see whether that file is an ES module, and use that to determine:

- how to find other modules which that file imports

- and how to transform that file if producing outputs

When a .ts file is compiled as an ES module, ECMAScript import/export syntax is left alone in the .js output; when it’s compiled as a CommonJS module, it will produce the same output you get today under --module commonjs.

What this also means is that resolving paths works differently in .ts files that are ES modules than they do in ES modules. For example, let’s say you have the following code today:

// ./foo.ts

export function helper() {

// ...

}

// ./bar.ts

import { helper } from "./foo"; // only works in CJS

helper();

This code works in CommonJS modules, but will fail in ES modules because relative import paths need to use extensions. As a result, it will have to be rewritten to use the extension of the output of foo.ts – so bar.ts will instead have to import from ./foo.js.

// ./bar.ts

import { helper } from "./foo.js"; // works in ESM & CJS

helper();

This might feel a bit cumbersome at first, but TypeScript tooling like auto-imports and path completion will typically just do this for you.

One other thing to mention is the fact that this applies to .d.ts files too. When TypeScript finds a .d.ts file in package, it is interpreted based on the containing package.

New File Extensions

The type field in package.json is nice because it allows us to continue using the .ts and .js file extensions which can be convenient; however, you will occasionally need to write a file that differs from what type specifies. You might also just prefer to always be explicit.

Node.js supports two extensions to help with this: .mjs and .cjs. .mjs files are always ES modules, and .cjs files are always CommonJS modules, and there’s no way to override these.

In turn, TypeScript supports two new source file extensions: .mts and .cts. When TypeScript emits these to JavaScript files, it will emit them to .mjs and .cjs respectively.

Furthermore, TypeScript also supports two new declaration file extensions: .d.mts and .d.cts. When TypeScript generates declaration files for .mts and .cts, their corresponding extensions will be .d.mts and .d.cts.

Using these extensions is entirely optional, but will often be useful even if you choose not to use them as part of your primary workflow.

CommonJS Interop

Node.js allows ES modules to import CommonJS modules as if they were ES modules with a default export.

// ./foo.cts

export function helper() {

console.log("hello world!");

}

// ./bar.mts

import foo from "./foo.cjs";

// prints "hello world!"

foo.helper();

In some cases, Node.js also synthesizes named exports from CommonJS modules, which can be more convenient. In these cases, ES modules can use a “namespace-style” import (i.e. import * as foo from "..."), or named imports (i.e. import { helper } from "...").

// ./foo.cts

export function helper() {

console.log("hello world!");

}

// ./bar.mts

import { helper } from "./foo.cjs";

// prints "hello world!"

foo.helper();

There isn’t always a way for TypeScript to know whether these named imports will be synthesized, but TypeScript will err on being permissive and use some heuristics when importing from a file that is definitely a CommonJS module.

One TypeScript-specific note about interop is the following syntax:

import foo = require("foo");

In a CommonJS module, this just boils down to a require() call, and in an ES module, this imports createRequire to achieve the same thing. This will make code less portable on runtimes like the browser (which don’t support require()), but will often be useful for interoperability. In turn, you can write the above example using this syntax as follows:

// ./foo.cts

export function helper() {

console.log("hello world!");

}

// ./bar.mts

import foo = require("./foo.cjs");

foo.helper()

Finally, it’s worth noting that the only way to import ESM files from a CJS module is using dynamic import() calls. This can present challenges, but is the behavior in Node.js today.

You can read more about ESM/CommonJS interop in Node.js here.

package.json Exports, Imports, and Self-Referencing

Node.js supports a new field for defining entry points in package.json called "exports". This field is a more powerful alternative to defining "main" in package.json, and can control what parts of your package are exposed to consumers.

Here’s an package.json that supports separate entry-points for CommonJS and ESM:

// package.json

{

"name": "my-package",

"type": "module",

"exports": {

".": {

// Entry-point for `import "my-package"` in ESM

"import": "./esm/index.js",

// Entry-point for `require("my-package") in CJS

"require": "./commonjs/index.cjs",

},

},

// CJS fall-back for older versions of Node.js

"main": "./commonjs/index.cjs",

}

There’s a lot to this feature, which you can read more about on the Node.js documentation. Here we’ll try to focus on how TypeScript supports it.

With TypeScript’s original Node support, it would look for a "main" field, and then look for declaration files that corresponded to that entry. For example, if "main" pointed to ./lib/index.js, TypeScript would look for a file called ./lib/index.d.ts. A package author could override this by specifying a separate field called "types" (e.g. "types": "./types/index.d.ts").

The new support works similarly with import conditions. By default, TypeScript overlays the same rules with import conditions – if you write an import from an ES module, it will look up the import field, and from a CommonJS module, it will look at the require field. If it finds them, it will look for a corresponding declaration file. If you need to point to a different location for your type declarations, you can add a "types" import condition.

// package.json

{

"name": "my-package",

"type": "module",

"exports": {

".": {

// Entry-point for `import "my-package"` in ESM

"import": "./esm/index.js",

// Entry-point for `require("my-package") in CJS

"require": "./commonjs/index.cjs",

// Entry-point for TypeScript resolution

"types": "./types/index.d.ts"

},

},

// CJS fall-back for older versions of Node.js

"main": "./commonjs/index.cjs",

// Fall-back for older versions of TypeScript

"types": "./types/index.d.ts"

}

TypeScript also supports the "imports" field of package.json in a similar manner (looking for declaration files alongside corresponding files), and supports packages self-referencing themselves. These features are generally not as involved, but are supported.

Your Feedback Wanted!

As we continue working on TypeScript 4.5, we expect to see more documentation and polish go into this functionality. Supporting these new features has been an ambitious under-taking, and that’s why we’re looking for early feedback on it! Please try it out and let us know how it works for you. For more information, you can see the implementing PR here

Supporting lib from node_modules

To ensure that TypeScript and JavaScript support works well out of the box, TypeScript bundles a series of declaration files (.d.ts files). These declaration files represent the available APIs in the JavaScript language, and the standard browser DOM APIs. While there are some reasonable defaults based on your target, you can pick and choose which declaration files your program uses by configuring the lib setting in the tsconfig.json.

There are two occasional downsides to including these declaration files with TypeScript though:

- When you upgrade TypeScript, you’re also forced to handle changes to TypeScript’s built-in declaration files, and this can be a challenge when the DOM APIs change as frequently as they do.

- It is hard to customize these files to match your needs with the needs of your project’s dependencies (e.g. if your dependencies declare that they use the DOM APIs, you might also be forced into using the DOM APIs).

TypeScript 4.5 introduces a way to override a specific built-in lib in a manner similar to how @types/ support works. When deciding which lib files TypeScript should include, it will first look for a scoped @typescript/lib-* package in node_modules. For example, when including dom as an option in lib, TypeScript will use the types in node_modules/@typescript/lib-dom if available.

You can then use your package manager to install a specific package to take over for a given lib For example, today TypeScript publishes versions of the DOM APIs on @types/web. If you wanted to lock your project to a specific version of the DOM APIs, you could add this to your package.json:

{

"dependencies": {

"@typescript/lib-dom": "npm:@types/web"

}

}

Then from 4.5 onwards, you can update TypeScript and your dependency manager’s lockfile will ensure that it uses the exact same version of the DOM types. That means you get to update your types on your own terms.

We’d like to give a shout-out to saschanaz who has been extremely helpful and patient as we’ve been building out and experimenting with this feature.

For more information, you can see the implementation of this change.

The Awaited Type and Promise Improvements

TypeScript 4.5 introduces a new utility type called the Awaited type. This type is meant to model operations like await in async functions, or the .then() method on Promises – specifically, the way that they recursively unwrap Promises.

// A = string

type A = Awaited<Promise<string>>;

// B = number

type B = Awaited<Promise<Promise<number>>>;

// C = boolean | number

type C = Awaited<boolean | Promise<number>>;

The Awaited type can be helpful for modeling existing APIs, including JavaScript built-ins like Promise.all, Promise.race, etc. In fact, some of the problems around inference with Promise.all served as motivations for Awaited. Here’s an example that fails in TypeScript 4.4 and earlier.

declare function MaybePromise<T>(value: T): T | Promise<T> | PromiseLike<T>;

async function doSomething(): Promise<[number, number]> {

const result = await Promise.all([

MaybePromise(100),

MaybePromise(200)

]);

// Error!

//

// [number | Promise<100>, number | Promise<200>]

//

// is not assignable to type

//

// [number, number]

return result;

}

Now Promise.all leverages combines certain features with Awaited to give much better inference results, and the above example works.

For more information, you can read about this change on GitHub.

Template String Types as Discriminants

TypeScript 4.5 now can narrow values that have template string types, and also recognizes template string types as discriminants.

As an example, the following used to fail, but now successfully type-checks in TypeScript 4.5.

export interface Success {

type: `${string}Success`;

body: string;

}

export interface Error {

type: `${string}Error`;

message: string;

}

export function handler(r: Success | Error) {

if (r.type === "HttpSuccess") {

// 'r' has type 'Success'

let token = r.body;

}

}

For more information, see the change that enables this feature.

--module es2022

Thanks to Kagami S. Rosylight, TypeScript now supports a new module setting: es2022. The main feature in --module es2022 is top-level await, meaning you can use await outside of async functions. This was already supported in --module esnext (and now--module nodenext), but es2022 is the first stable target for this feature.

You can read up more on this change here.

Tail-Recursion Elimination on Conditional Types

TypeScript often needs to gracefully fail when it detects possibly infinite recursion, or any type expansions that can take a long time and affect your editor experience. As a result, TypeScript has heuristics to make sure it doesn’t go off the rails when trying to pick apart an infinitely-deep type, or working with types that generate a lot of intermediate results.

type InfiniteBox<T> = { item: InfiniteBox<T> }

type Unpack<T> = T extends { item: infer U } ? Unpack<U> : T;

// error: Type instantiation is excessively deep and possibly infinite.

type Test = Unpack<InfiniteBox<number>>

The above example is intentionally simple and useless, but there are plenty of types that are actually useful, and unfortunately trigger our heuristics. As an example, the following TrimLeft type removes spaces from the beginning of a string-like type. If given a string type that has a space at the beginning, it immediately feeds the remainder of the string back into TrimLeft.

type TrimLeft<T extends string> =

T extends ` ${infer Rest}` ? TrimLeft<Rest> : T;

// Test = "hello" | "world"

type Test = TrimLeft<" hello" | " world">;

This type can be useful, but if a string has 50 leading spaces, you’ll get an error.

type TrimLeft<T extends string> =

T extends ` ${infer Rest}` ? TrimLeft<Rest> : T;

// error: Type instantiation is excessively deep and possibly infinite.

type Test = TrimLeft<" oops">;

That’s unfortunate, because these kinds of types tend to be extremely useful in modeling operations on strings – for example, parsers for URL routers. To make matters worse, a more useful type typically creates more type instantiations, and in turn has even more limitations on input length.

But there’s a saving grace: TrimLeft is written in a way that is tail-recursive in one branch. When it calls itself again, it immediately returns the result and doesn’t do anything with it. Because these types don’t need to create any intermediate results, they can be implemented more quickly and in a way that avoids triggering many of type recursion heuristics that are built into TypeScript.

That’s why TypeScript 4.5 performs some tail-recursion elimination on conditional types. As long as one branch of a conditional type is simply another conditional type, TypeScript can avoid intermediate instantiations. There are still heuristics to ensure that these types don’t go off the rails, but they are much more generous.

Keep in mind, the following type won’t be optimized, since it uses the result of a conditional type by adding it to a union.

type GetChars<S> =

S extends `${infer Char}${infer Rest}` ? Char | GetChars<Rest> : never;

If you would like to make it tail-recursive, you can introduce a helper that takes an “accumulator” type parameter, just like with tail-recursive functions.

type GetChars<S> = GetCharsHelper<S, never>;

type GetCharsHelper<S, Acc> =

S extends `${infer Char}${infer Rest}` ? GetCharsHelper<Rest, Char | Acc> : Acc;

You can read up more on the implementation here.

Disabling Import Elision

There are some cases where TypeScript can’t detect that you’re using an import. For example, take the following code:

import { Animal } from "./animal.js";

eval("console.log(new Animal().isDangerous())");

By default, TypeScript always removes this import because it appears to be unused. In TypeScript 4.5, you can enable a new flag called --preserveValueImports to prevent TypeScript from stripping out any imported values from your JavaScript outputs. Good reasons to use eval are few and far between, but something very similar to this happens in Svelte:

<!-- A .svelte File -->

<script>

import { someFunc } from "./some-module.js";

</script>

<button on:click={someFunc}>Click me!</button>

along with in Vue.js, using its <script setup> feature:

<!-- A .vue File -->

<script setup>

import { someFunc } from "./some-module.js";

</script>

<button @click="someFunc">Click me!</button>

These frameworks generate some code based on markup outside of their <script> tags, but TypeScript only sees code within the <script> tags. That means TypeScript will automatically drop the import of someFunc, and the above code won’t be runnable! With TypeScript 4.5, you can use --preserveValueImports to avoid these situations.

Note that this flag has a special requirement when combined with --isolatedModules: imported types must be marked as type-only because compilers that process single files at a time have no way of knowing whether imports are values that appear unused, or a type that must be removed in order to avoid a runtime crash.

// Which of these is a value that should be preserved? tsc knows, but `ts.transpileModule`,

// ts-loader, esbuild, etc. don't, so `isolatedModules` gives an error.

import { someFunc, BaseType } from "./some-module.js";

// ^^^^^^^^

// Error: 'BaseType' is a type and must be imported using a type-only import

// when 'preserveValueImports' and 'isolatedModules' are both enabled.

That makes another TypeScript 4.5 feature, type modifiers on import names, especially important.

For more information, see the pull request here.

type Modifiers on Import Names

As mentioned above, --preserveValueImports and --isolatedModules have special requirements so that there’s no ambiguity for build tools whether it’s safe to drop type imports.

// Which of these is a value that should be preserved? tsc knows, but `ts.transpileModule`,

// ts-loader, esbuild, etc. don't, so `isolatedModules` issues an error.

import { someFunc, BaseType } from "./some-module.js";

// ^^^^^^^^

// Error: 'BaseType' is a type and must be imported using a type-only import

// when 'preserveValueImports' and 'isolatedModules' are both enabled.

When these options are combined, we need a way to signal when an import can be legitimately dropped. TypeScript already has something for this with import type:

import type { BaseType } from "./some-module.js";

import { someFunc } from "./some-module.js";

export class Thing implements BaseType {

// ...

}

This works, but it would be nice to avoid two import statements for the same module. That’s part of why TypeScript 4.5 allows a type modifier on individual named imports, so that you can mix and match as needed.

import { someFunc, type BaseType } from "./some-module.js";

export class Thing implements BaseType {

someMethod() {

someFunc();

}

}

In the above example, BaseType is always guaranteed to be erased and someFunc will be preserved under --preserveValueImports, leaving us with the following code:

import { someFunc } from "./some-module.js";

export class Thing {

someMethod() {

someFunc();

}

}

For more information, see the changes on GitHub.

Private Field Presence Checks

TypeScript 4.5 supports an ECMAScript proposal for checking whether an object has a private field on it. You can now write a class with a #private field member and see whether another object has the same field by using the in operator.

class Person {

#name: string;

constructor(name: string) {

this.#name = name;

}

equals(other: unknown) {

return other &&

typeof other === "object" &&

#name in other && // <- this is new!

this.#name === other.#name;

}

}

One interesting aspect of this feature is that the check #name in other implies that other must have been constructed as a Person, since there’s no other way that field could be present. This is actually one of the key features of the proposal, and it’s why the proposal is named “ergonomic brand checks” – because private fields often act as a “brand” to guard against objects that aren’t instances of their class. As such, TypeScript is able to appropriately narrow the type of other on each check, until it ends up with the type Person.

We’d like to extend a big thanks to our friends at Bloomberg who contributed this pull request: Ashley Claymore, Titian Cernicova-Dragomir, Kubilay Kahveci, and Rob Palmer!

Import Assertions

TypeScript 4.5 supports an ECMAScript proposal for import assertions. This is a syntax used by runtimes to make sure that an import has an expected format.

import obj from "./something.json" assert { type: "json" };

The contents of these assertions are not checked by TypeScript since they’re host-specific, and are simply left alone so that browsers and runtimes can handle them (and possibly error).

// TypeScript is fine with this.

// But your browser? Probably not.

import obj from "./something.json" assert {

type: "fluffy bunny"

};

Dynamic import() calls can also use import assertions through a second argument.

const obj = await import("./something.json", {

assert: { type: "json" }

})

The expected type of that second argument is defined by a new type called ImportCallOptions, and currently only accepts an assert property.

We’d like to thank Wenlu Wang for implementing this feature!

Faster Load Time with realPathSync.native

TypeScript now leverages a system-native implementation of the Node.js realPathSync function on all operating systems.

Previously this function was only used on Linux, but in TypeScript 4.5 it has been adopted to operating systems that are typically case-insensitive, like Windows and MacOS. On certain codebases, this change sped up project loading by 5-13% (depending on the host operating system).

For more information, see the original change here, along with the 4.5-specific changes here.

Snippet Completions for JSX Attributes

TypeScript 4.5 brings snippet completions for JSX attributes. When writing out an attribute in a JSX tag, TypeScript will already provide suggestions for those attributes; but with snippet completions, they can remove a little bit of extra typing by adding an initializer and putting your cursor in the right place.

TypeScript will typically use the type of an attribute to figure out what kind of initializer to insert, but you can customize this behavior in Visual Studio Code.

Keep in mind, this feature will only work in newer versions of Visual Studio Code, so you might have to use an Insiders build to get this working. For more information, read up on the original pull request

Better Editor Support for Unresolved Types

In some cases, editors will leverage a lightweight “partial” semantic mode – either while the editor is waiting for the full project to load, or in contexts like GitHub’s web-based editor.

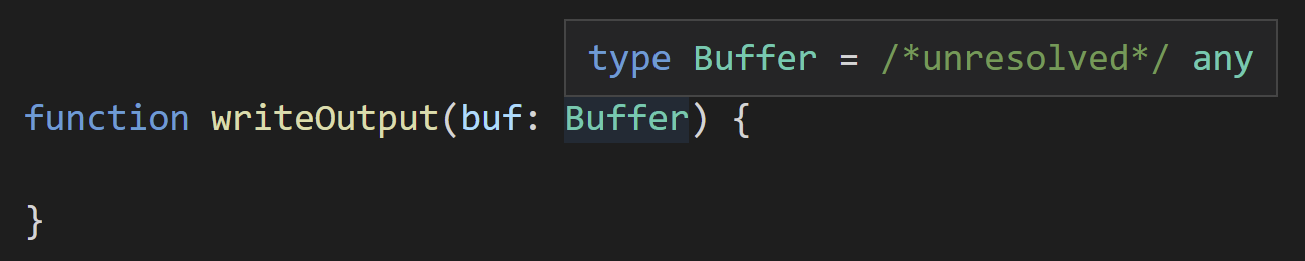

In older versions of TypeScript, if the language service couldn’t find a type, it would just print any.

In the above example, Buffer wasn’t found, so TypeScript replaced it with any in quick info. In TypeScript 4.5, TypeScript will try its best to preserve what you wrote.

However, if you hover over Buffer itself, you’ll get a hint that TypeScript couldn’t find Buffer.

Altogether, this provides a smoother experience when TypeScript doesn’t have the full program available. Keep in mind, you’ll always get an error in regular scenarios to tell you when a type isn’t found.

For more information, see the implementation here.

Breaking Changes

lib.d.ts Changes

TypeScript 4.5 contains changes to its built-in declaration files which may affect your compilation; however, these changes were fairly minimal, and we expect most code will be unaffected.

Inference Changes from Awaited

Because Awaited is now used in lib.d.ts and as a result of await, you may see certain generic types change that might cause incompatibilities; however, given many intentional design decisions around Awaited to avoid breakage, we expect most code will be unaffected.

Compiler Options Checking at the Root of tsconfig.json

It’s an easy mistake to accidentally forget about the compilerOptions section in a tsconfig.json. To help catch this mistake, in TypeScript 4.5, it is an error to add a top-level field which matches any of the available options in compilerOptions without having also defined compilerOptions in that tsconfig.json.

What’s Next?

After this beta release, the team will be focusing on fixing issues and adding polish for our release candidate (RC). The sooner you can try out our beta and provide feedback, the sooner we can ensure that new features and existing issues are addressed, and once those changes land, they’ll be available in our nightly releases which tend to be very stable. To plan accordingly, you can take a look at our release schedule on TypeScript 4.5’s iteration plan.

So try out TypeScript 4.5 Beta today, and let us know what you think!

Happy Hacking!

– Daniel Rosenwasser and the TypeScript Team

I believe editor support for vscode link suppose to redirect to ‘https://code.visualstudio.com/Docs/languages/typescript#_how-can-i-use-the-latest-typescript-beta-with-vs-code‘

I believe this should be a code sample for the named c[tj]s import (there is no foo namespace):

// ./foo.cts export function helper() { console.log("hello world!"); } // ./bar.mts import { helper } from "./foo.cjs"; // prints "hello world!" -foo.helper(); +helper();Nice work!

Sorry if this is a dumb question, but in what situation would a type like `TrimLeft` ever be useful?

Will `moduleResolution` also support `node12`/`nodenext`? e.g. In a create-react-app one might want `”module”: “esnext”` with `”moduleResolution”: “nodenext”`.

Hi, small typo in the code example of Awaited

-export interface Success { +export interface Error { type: `${string}Error`; message: string; }