Sustainable Software Engineering (SSE) and the role and responsibilities of a Sustainable Software Engineer

Does Sustainable Software Engineering (SSE) deal with the same topics of Software Optimization or Cost Optimization?

What does writing “green software” mean? The Internet has got lots of literature about this matter, but at the end of the story there is still much confusion about the role of a Sustainable Software Engineer and its responsibilities. Let’s try to make this clearer.

If you look at the principles of green software engineering, you may find a series of points to reduce carbon emissions produced by servers running your apps, through several kinds of optimizations. These points can induce you to think that you are following SSE best practices, but looking closer, they match exactly with classical guidance in software and cost optimization. App optimization is a topic that has already been consolidated for several decades, especially with the growth of cloud computing, so where is the news?

Reading more carefully, you may find sentences as:

“As Green Software Engineers, we recognize there are many advantages to building sustainable applications. They are almost always cheaper, they are often more performant, they are often more resilient. But the primary reason we are practicing Green Software Engineering is for sustainability, everything else is an added advantage”

My interpretation on the topic may be summarized in that single concept: when you are optimizing your applications, you are contextually implementing your software towards sustainable patterns. Software optimization and cost optimization are clearly practices which reduce carbon emissions, but this saving is substantially a (albeit very welcome) side effect derived from the optimizations themselves.

As a software architect, I always wrote applications according to these practices. So, I could state that under those assumptions:

- I am a good architect

- I am not an IT masochist 😊

Software architects should always strive to write the best performing applications in terms of CPU, resources, and network usage, and according to the service level agreed with stakeholders. My deduction is therefore that cost and software optimization practices are minimally related to the SSE matter.

Cost and software optimization are tasks for architects. Actions done towards building green software are something relatively different, which must justify the “added value” of SSE. Then you may wear both hats, but this is another story.

Does SSE deal with Carbon Emission Optimizations into a specific Datacenter (cloud or on-premises)?

Carbon emissions of an application mainly depend on two main factors:

- How the application is architected and implemented

- In what environment that application is deployed and what kind of resources – provided by the environment – that application uses.

Only the first point is the responsibility of a Sustainable Software Engineer. The second one is related to the datacenter, and how much IT engineers that operate in that datacenter care about the sustainability cause. An SSE should be accountable but not responsible for this.

Let’s suppose that our application is built to be green (we will drill down through these aspects later). If we deploy this app in a datacenter which is not compliant with sustainable practices, then the whole system is not green. Since there’s nothing to do at application level, we can conclude that datacenter optimizations are not strictly related to SSE role.

To enforce this concept, let’s look at three possible levels of optimization in which IT engineers can operate to optimize an environment and consequently the whole datacenter:

- PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness): PUE is a ratio between the entire datacenter power used, and the power needed by only the hardware components. It’s easy to catch that this metric depends only on the datacenter itself.

- Carbon Emission Factor (CEF): CEF is the sum of emissions of CO2eq of the human activity described as mass unit of CO2eq / reference flows. Even this metric depends only on the datacenter itself. Please note that even if you are going cloud and your provider guarantees that their datacenters are powered only with alternative energy, that datacenter still has carbon emissions due to scope 3 emissions. This means that deploying any app on a datacenter which is fully alternative-powered is not enough to declare it 100% carbon free 😊

- Hardware Optimization Factor (HOF): this aspect is the most difficult to manage, and equally difficult is to state and declare a hardware “optimized” for the applications it hosts. A whole article should be needed to go into detail in such a matter so I will try to summarize a couple of concepts deduced from the computational load calculation in the most of next gen computers:

-

- bringing your computational load (that is CPU utilization on the physical servers) from 10% to 40% raises only by 1,7 factor the power draw needed for that server.

- If computational load is near 0% (apps are idle or absent), the physical server still has an important power draw, which is counterproductive in terms of carbon emissions efficiency.

Virtualization, containerization and – most of all – the use of cloud PaaS resources are the main factors which allow a datacenter to maintain computational load metric optimized. Like PUE and CEF, even this optimization practice depends only on the datacenter organization and consequently is not an SSE task.

So, what should a Sustainable Software Engineer be responsible of?

One of the main mistakes that a Sustainable Software Engineer might make is starting to measure utilization metrics of all resources used by the software and arrive too quickly to fallacious conclusions. SSE isn’t (only) about resource consumption KPIs. They may be useful, but only when contextualized with other most relevant values.

Let’s take an example: you could measure a huge resources utilization for your app, in terms of CPU, memory and networking. After having measured them, you may consequently think: “oh my gosh, my application is not green at all!”. Nothing could be more wrong: if you run a NASA critical application which governs all USA satellites in outer space, probably that app would be a resource’s leech. On the contrary, if you can demonstrate that it is hardware resource optimized, then it may be perfectly green.

Let’s do another example: I write an application which manages fantasy football leagues. That application is incredibly fast! Loads pages in terms of milliseconds, reads data locally quickly, caches most of the data cleverly, and does intelligent data retention.

- Is that application resource optimized? Under the assumption that I’m a good software architect, and according to what I said before, probably yes.

- Is that application green? Well, to reach those performance standards – like the milliseconds load time – I probably have used a lot of precious, expensive, and heavy carbon emitting resources. Can a fantasy football player afford to wait for a slower page loading? Yes! Because that functionality is not critical and doesn’t impact on any economic factor cause your competition meets similar performances. Having said that, we may finally state that my fantasy football application is not green.

To determine if an application runs green, and under the assumption that the app is cost-and-resource optimized, a Sustainable Software Engineer must consider 3 crucial factors:

- Resource utilization metrics

- User experience metrics (mainly measured by service wait time under an average user load)

- Deployment scenarios, which divide different kinds of applications into a series of categories. Each of those categories may address some performance standards typical for that business target.

Without any of these 3 elements, it is not possible to determine if an application is running green!

Deployment scenarios and App categorization

Let’s start with a style exercise (not easy at all…). Let’s distribute all applications into a series of buckets representing software categories and, consequently, into a plethora of business scenarios:

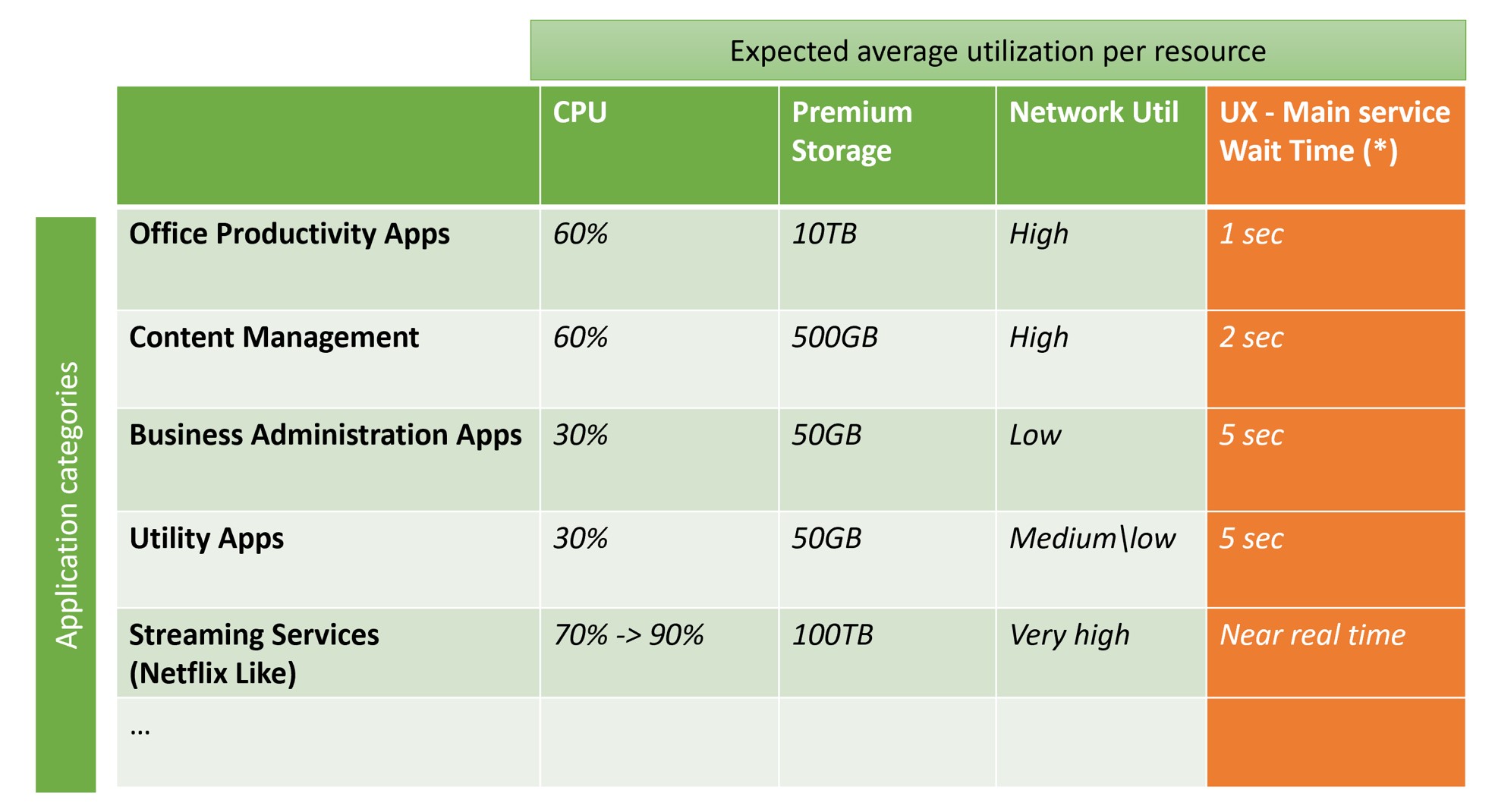

- Office Productivity Apps: The most famous app in this category could be a mail server, like Microsoft Exchange. Usually, these applications need high storage and elevated CPU utilization. They generate a high volume of “user access” with important SLA metrics to consider.

- Content Management: in this category you may find mainly CRM and CMS software, like Microsoft SharePoint. Resource requirements are like the above category, but with a lower CPU consumption.

- Business Administration Apps: this is the bucket in which classical LOB (Line-of-Business) applications fall, like Human resources software, accounting software e financial management software. Most of times, a LOB application has medium\low storage needs and low CPU usage, because it impacts a limited number of users (the employees).

- Utility Apps: typical apps which may fit into this category are file storage and collaboration and asset sharing software like Microsoft OneDrive. They often need high storage, but they have medium\low expected SLAs.

- Digital Media Asset Management (DAM) \ Streaming Services: Netflix, Amazon Prime and Google Play are the most famous platform in this category. The software running these services is very resource and network consuming and, due to the high competition in the segment, it must have a very fast user experience with a near real time page loading.

We can carry on categorizing applications defining many other buckets, like AI Application, Cognitive Services, BOT, Machine Learning apps, Edge Computing and IoT solutions, but it’s not the scope of this document defining them all (I might do a deep dive in my next post though).

When this classification will be completed in detail, we may draw a matrix representation of the average resources consumption by every application category, plus the important column representing the User Experience impact measured in “expected maximum wait time” for the service page’s loading:

(*) under an “average” user load.

We can now finally focus on what can be tasks related to SSE:

- Imagine a complex system, probably based on machine learning features, taking care of all those metrics. Any variations on those KPIs may generate a warning or an alert in a dedicated dashboard, and any of these should be related to actions.

Please note that in the SSE world a degradation in the UX could be not necessarily bad news, even if it’s very important to stay into certain usability boundaries if you don’t want your users to leave the app and migrate to competition.

In literature it is easy to find some basic response time recommendations: Jakob Nielsen back in 1993 outlined 3 main metrics for response time. While this summary may seem outdated, the metrics are still meaningful as they are generally based on the way human attention performs:

- 0,1 second – the limit after which the system reaction doesn’t seem instantaneous.

- 1 second – when user will notice the delay, but without interrupted flow of thought.

- 10 seconds – when user attention is completely lost.

Usually, an ordinary user may feel very upset when reaching this 10-second threshold, as about 40 percent of users will abandon application immediately. That’s to say that implementing rules to put in place when collecting SSE metrics, it’s not an easy job. In my next posts, we will drill down into those in detail, specifying when to raise warnings and alerts, and possible related actions with the purpose of keeping an app green.

Stay tuned…

Light

Light Dark

Dark

1 comment

This entire exercise strikes me as rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. Sure, you might make people more comfortable for a few more minutes, but it is entirely meaningless with regards to the ultimate outcome.