Intro

Our ISE team at Microsoft recently completed an engagement with a large industrial customer. The system we developed was distributed between the edge and the cloud and made use of technologies including Python, Azure IoT, Kubernetes, Redis and Dapr. The system was built prior to this engagement and our goal for this phase was to make the system production ready and handle a greater scale of messages.

In this system, messages originating from the edge would be sent to the cloud where they would be augmented with additional data from the company’s various internal APIs and document storage. Augmented messages would then be processed further in the system; however, this blog post will focus on features surrounding the augmenting process.

Problems

From initial investigations a couple of problems were observed within the message augmentation process.

Speed of processing

A single message could take up to as much as a minute to go through the full augmentation process. With our goal in mind this was deemed insufficient.

Influencing factors:

- In some cases the data returned from the APIs was very large.

- Only basic caching was in place and many messages required the same data resulting in repeated retrieval and processing of the same data.

- Some of the company’s internal APIs had ‘rate limiting’ in place. Meaning, if the rate limit was hit, we would have to wait a determined length of time before attempting to call again.

- Each message was processed sequentially, and each step of the augmentation was performed sequentially as well.

Out of memory exceptions

On the container performing the augmentation process exit code 137 / OOMKilled was observed frequently. This was a significant problem as this would cause the message being processed at the time of error to be dropped.

The major contributor to this was the way external documents were processed from the Storage Accounts by using the .readall() method of the Azure storage client library. Reading the entire document into memory with large documents was easy to encounter the container memory limit and cause the container to be shutdown.

Example below, taken from Download a blob with Python – Azure Storage | Microsoft Learn, shows downloading the complete contents of the sample-blob.txt file using this method and prints the contents.

def download_blob_to_string(self, blob_service_client: BlobServiceClient, container_name):

blob_client = blob_service_client.get_blob_client(container=container_name, blob="sample-blob.txt")

# encoding param is necessary for readall() to return str, otherwise it returns bytes

downloader = blob_client.download_blob(max_concurrency=1, encoding='UTF-8')

blob_text = downloader.readall()

print(f"Blob contents: {blob_text}")No queuing

Any message sent to the cloud was attempted to be processed immediately. No queuing system was in place. Being cautious of future growth in the system and the number of messages it may process, this was deemed a problem.

Solutions

This next section will describe a number of actions taken to resolve the problems previously identified.

Dedicated Caching Process

We introduced a separate process with the sole purpose of building a cache of frequently used data between messages. This ran in its own container on a CRON schedule, allowing easy control of how frequently we update the cache.

This separation of concerns gave many advantages:

- This reduced the need to lookup / filter any commonly used data from APIs or data storage, resulting in faster message processing.

- Avoids situations where a failure in accessing data sources does not result in a failure of processing a message.

- Significant reduction in memory usage during message processing. Higher memory usage is only observed during building of cache, but this is known and manageable. Memory and CPU can be added to the container to speed up the cache building process, but having lower limits no longer affects the message processing.

- When we scale to have multiple instances of the augmentation process, they can all share the same cached data.

Redis Queue / Dapr

A cloud side queue was implemented to ingest edge messages and have the augmentation process consume messages from the queue for processing.

This was done with a Redis container for the queue which was then accessed via Dapr.

Dapr was chosen as it provides an interface to a variety of backend implementations of queueing / storage etc. The team had considerations of other queuing implementations, such as Azure Event Grid. With Dapr in place if the customer development team wish to rework their architecture this will be easy to do.

The code sample below demonstrates publishing events to queue with the DaprClient class. As can be seen, there is no reference to the underlying implementation. Example source How to: Publish a message and subscribe to a topic | Dapr Docs.

with DaprClient() as client:

result = client.publish_event(

pubsub_name=PUBSUB_NAME,

topic_name=TOPIC_NAME,

data=json.dumps(my_data),

data_content_type='application/json',

)The next sample shows the subscription to a topic. Sample taken from Declarative, streaming, and programmatic subscription types | Dapr Docs.

from cloudevents.sdk.event import v1

@app.route('/orders', methods=['POST'])

def process_order(event: v1.Event) -> None:

data = json.loads(event.Data())

logging.info('Subscriber received: ' + str(data))The reference to the Redis implementation is defined within a Dapr Component configuration file.

An example Redis pub/sub component definition follows Redis Streams | Dapr Docs.

apiVersion: dapr.io/v1alpha1

kind: Component

metadata:

name: redis-pubsub

spec:

type: pubsub.redis

version: v1

metadata:

- name: redisHost

value: localhost:6379

- name: redisPassword

value: "<Password>"

- name: consumerID

value: "channel1"

- name: useEntraID

value: "true"

- name: enableTLS

value: "false"The complimenting subscription definition is as follows How to: Publish a message and subscribe to a topic | Dapr Docs.

apiVersion: dapr.io/v2alpha1

kind: Subscription

metadata:

name: order-pub-sub

spec:

topic: orders

routes:

default: /orders

pubsubname: redis-pubsub

scopes:

- orderprocessing Read docs as a stream

As previously mentioned, when reading documents from blob storage the system used the .readall() method loading the complete document into memory. It was not foreseen that we would read such large documents for this to be a problem.

The method of reading was changed to read documents by chunks as a stream.

Note: This approach is best suited to data that can be consumed in chunks or lines E.g.

.csvor textual data.

Example below shows the equivalent from the previous sample now iterating on each chunk of the document.

def download_blob_chunks(self, blob_service_client: BlobServiceClient, container_name):

blob_client = blob_service_client.get_blob_client(container=container_name, blob="sample-blob.txt")

# This returns a StorageStreamDownloader

stream = blob_client.download_blob()

chunk_list = []

# Read data in chunks to avoid loading all into memory at once

for chunk in stream.chunks():

# Process your data (anything can be done here - 'chunk' is a byte array)

chunk_list.append(chunk)Source Download a blob with Python – Azure Storage | Microsoft Learn.

Load testing

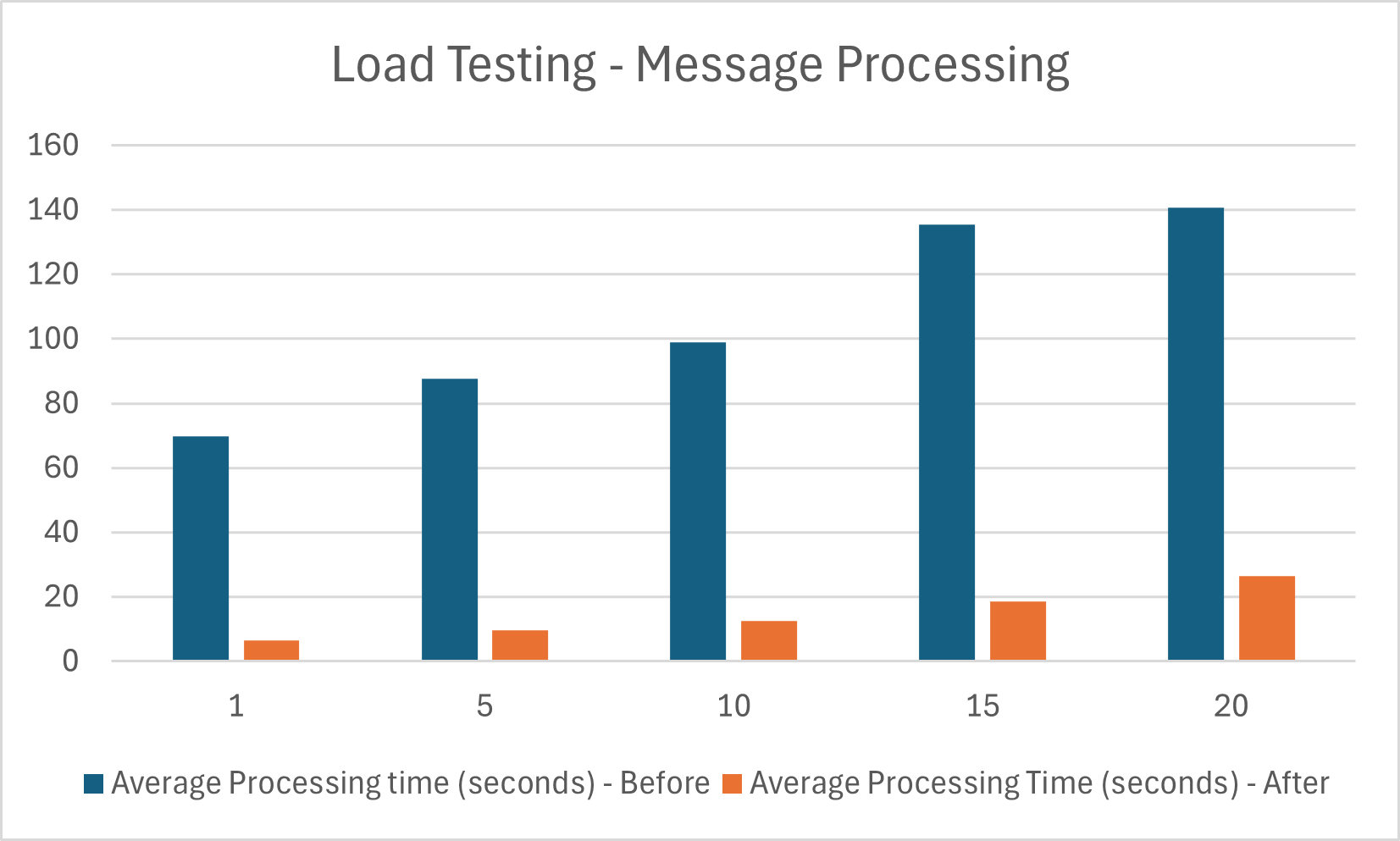

Load testing was performed at the beginning of the project and after the discussed changes were implemented.

The graph below demonstrates the change in performance. Here we measure the time taken to process a number of messages.

As you can see, a significant performance improvement has been made. These changes have been successful in contributing to the goal of having the system production ready and to be able to handle a greater scale of messages.

Future Improvements

Storage with Dapr

Dapr has the ability to abstract state storage in a similar fashion to the queue mechanism previously described. Quickstart demo available here.

with DaprClient() as client:

# Save state into the state store

client.save_state(DAPR_STORE_NAME, orderId, str(order))

logging.info('Saving Order: %s', order)

# Get state from the state store

result = client.get_state(DAPR_STORE_NAME, orderId)

logging.info('Result after get: ' + str(result.data))

# Delete state from the state store

client.delete_state(store_name=DAPR_STORE_NAME, key=orderId)

logging.info('Deleting Order: %s', order)Here we use the DaprClient class to interface with the underlying state storage implementation.

With an appropriate state storage component file defined. Such as the following for Azure Blob Storage.

apiVersion: dapr.io/v1alpha1

kind: Component

metadata:

name: <NAME>

spec:

type: state.azure.blobstorage

version: v2

metadata:

- name: accountName

value: "[your_account_name]"

- name: accountKey

value: "[your_account_key]"

- name: containerName

value: "[your_container_name]"Similarly to the queuing system, this provides the flexibility to change the implemented storage backend via configuration and not code.

Scaling

Current Scaling

The augmentation process container is currently scaled using the Kubernetes built-in Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) to increase the number of instances. Scaling is based on CPU %, with the assumption that when we have high CPU usage we are processing a high number of messages.

An example Helm chart for HPA is as follows:

apiVersion: autoscaling/v1

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: contextualizer

namespace: default

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: contextualizer

minReplicas: 1

maxReplicas: 5

metrics:

- type: Resource

resource:

name: cpu

target:

type: Utilization

averageUtilization: 75The value averageUtilization: 75 means that we calculate the average cpu utilization across the current set of pods and if we exceed 75 then the system will scale.

Further details on HPA can be found here.

KEDA

An alternative to HPA is the use of Kubernetes Event Driven Autoscaling (KEDA). As the name suggests this scaling framework is based on events/metrics observed elsewhere in the system. Further information can be found here

In our situation we could use the message queue length metric to determine when to increase or decrease the number of instances. This would ensure we are appropriately consuming in the incoming queue at a desired rate.

Scaling is achieved by defining a ScaledObject definition. An example with Azure EventHub is shown below.

apiVersion: keda.sh/v1alpha1

kind: ScaledObject

metadata:

name: azure-eventhub-scaled-object

namespace: default

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

name: azure-eventhub-function

minReplicaCount: 0 # Change to define how many minimum replicas you want

maxReplicaCount: 10

# The period to wait after the last trigger reported active before scaling the resource back to 0.

# By default it’s 5 minutes (300 seconds).

cooldownPeriod: 5

triggers:

- type: azure-eventhub

metadata:

# Required

storageConnectionFromEnv: AzureWebJobsStorage

# Required if not using Pod Identity

connectionFromEnv: EventHub

# Required if using Pod Identity

eventHubNamespace: AzureEventHubNameSpace

eventHubName: NameOfTheEventHub

# Optional

consumerGroup: $Default # default: $Default

unprocessedEventThreshold: "64" # default 64 events.

blobContainer: containerThe property unprocessedEventThreshold allows us to define the threshold the system will begin scaling from.

minReplicaCount and maxReplicaCount determine the number of replicas we scale to.

Key Take-aways

Testing

If you are in a situation where performance is a concern, having a quantitative measure of what you are attempting to improve is vital. The means of testing should also be easily repeatable in order to have comparisons before and after any changes.

Assumptions on data

Take care to analyse and not under-estimate the size of data to be consumed. The size of data used by the augmentation process was a significant contributor to the problems faced with out of memory exceptions and speed of processing. Had this been identified sooner, the initial system design could have changed to accommodate this.

Additionally, be aware of using functions such as .readall() method of the Azure storage client library and its effect on memory usage.

Queuing

When working with a system in which you want to process many messages and where such number of messages can fluctuate it is advisable to make use of a queueing mechanism. Allowing to to take advantage of common queue functions such as retry logic, dead-lettering and scaling based on queue metrics.