Written by Destiny Hillis (Software Engineer II), Rachel Johnson (Software Engineer II), Tempest van Schaik (Principal Data Scientist), and Yvonne Radsmikham (Senior Software Engineer).

Introduction

This year, we’ve been trying to use AI to improve our efficiency as software engineers and data scientists who build AI. We’re aiming for Hyper-Velocity Engineering (HVE), which is a high-performance, AI-accelerated approach to software that enables expert, multi-disciplinary teams to deliver production-quality outcomes at high speed, amplifying productivity, and unlocking high-ROI innovation.

In a recent initiative, our team at ISE collaborated with a healthcare organization to develop an AI solution that streamlines workflow for care staff supporting people with severe health ailments. We were excited to see Copilot rolled out to so many Microsoft products recently, especially Github Copilot for VSCode, where it could assist us with the development process. We had access to Copilot during development on this project, so we intentionally leaned on it to accelerate our work and experiments with creative ways it could help.

In this article, we share some of the most impactful uses we found for AI and what we learned in the process. We had the most success in using AI to:

- Create and test development how-to’s,

- Create class diagrams,

- Create data visualizations,

- Create demo video scripts.

One of our key takeaways is that using AI saved us a huge amount of time, making some activities at least twice as fast. When used in the wrong way, we actually found that it made some activities at least twice as slow!

Use-Case 1: Creating and Testing How-To’s

In any fast-paced engineering environment, documentation often falls behind. Even when it exists, it’s rarely treated as something that needs to be tested, unlike our code. But good documentation is just as essential, especially when it comes to onboarding new team members or ensuring that setup steps actually work outside your own machine.

That’s where GitHub Copilot, specifically its Agent Mode, comes in. While many developers are already using Copilot to help write code, we have found that fewer are using it to validate that their documentation is complete, accurate, and actionable. We explored how to treat our how-to guides like executable instructions by using Copilot in Agent Mode. Copilot acted as a first-time user: following each step, identifying gaps, and even generating missing components. This saved us time, improved accuracy, and made the project more accessible for contributors.

The Problem with Untested Docs

In our project, creating a new experiment wasn’t as simple as adding a single file. It involved adding and updating multiple files scattered across the codebase, remembering where everything needed to go, and often writing or updating tests. Unsurprisingly, steps would get skipped, and people would run into blockers if the instructions weren’t crystal clear. We realized that writing documentation wasn’t enough, we needed a way to confirm it actually worked in practice.

Traditionally, this process required someone deeply familiar with the system to spend hours documenting each step, testing what they’d written, and then asking another teammate to validate it. Depending on availability and complexity, this cycle could take days.

Testing our docs helped us catch issues we otherwise would have missed like outdated file paths. Without a test run, we wouldn’t have known they needed to be updated. Copilot also stepped in to help because it could detect when a path had changed, prompt the tester to supply it, and then continue generating the necessary file updates. It also filled in other common gaps, for example, suggesting missing libraries, prompting to install them, or even installing them automatically. If you forgot to start a virtual environment, Copilot would ask whether you wanted to create one.

We saw an opportunity to apply HVE techniques to speed up the process, reduce the burden on others, and improve overall coverage.

Our 3-Step Process with Github Copilot

The workflow we landed on was simple but effective: prepare your documentation, have Copilot follow it, and then validate the results.

- We began by drafting a structured README for our use-case, outlining each step needed to create a new experiment—from setting up the environment to adding tests. To accelerate this, we used Copilot to generate the first version with a prompt like: “Please create a README detailing how to create a new experiment, all the files that need to be created and edited, including tests.” Copilot gave us a solid starting point that we could tailor to our specific codebase. We kept a human in the loop to test the README manually, refining Copilot’s output by editing what was missing or wrong, trimming unnecessary parts, and simplifying steps.

- With the documentation ready, we switched gears and asked Copilot to act on it. In Agent Mode, Copilot can parse natural language instructions and turn them into concrete actions. A prompt like, “Use the info in this document to edit and/or create the relevant files. Ask me if you need any more details,” initiated the process. Copilot proceeded to generate the required Python files, configuration files, and even boilerplate test code, just as a new contributor would when trying to follow the guide manually. Prompting Copilot to ask if it needs more details helps to catch errors and gaps in the documentation as well as any missteps Copilot might take. This prompt was critical. Without it, Copilot may have missed context, like placing files in the wrong directory when it couldn’t resolve relative paths. By encouraging Copilot to ask for clarification, we turned failures into opportunities to improve both the documentation and Copilot’s performance.

- Finally, we used Copilot to validate the implementation. At this stage, we prompted it to review the code and identify anything that was missing. For example, a simple instruction like, “Let me know if any tests are missing. Please add them,” prompted Copilot to scan the codebase for gaps in test coverage. In our case, it correctly identified missing cases and generated appropriate test functions for our framework.

Final Thoughts on Creating and Testing How-To’s

Documentation is often the first thing a new contributor encounters, and the first thing to break as a project evolves. Using Copilot in Agent Mode to follow and validate your how-to guides brings the same rigor to documentation that we expect from code.

This approach not only catches errors early, it enhances onboarding and reduces support burdens. It’s especially valuable when we work directly with customers, since they inherit the codebase to maintain and extend. Auto-maintainable documentation becomes a lasting artifact that helps them long after delivery, outlives traditional docs, and establishes best practices that can spread across their enterprise. It’s a low-effort, high-impact way to level up your engineering workflow. AI tools like Copilot aren’t just for writing code, they’re redefining how we write, test, and maintain the docs that support it.

Use-Case 2: Creating Class Diagrams

As part of the efforts to update the documentation, we also explored how to create class diagrams to add a visual to clarify part of our system. This can be easily created manually when the number of classes are small, but with many classes and methods (our repo had 10 classes and over 90 attributes and methods for instance), creating a diagram from scratch would be very time consuming. There are tools on the market that can programmatically create class diagrams, but we saw that it did not always pick up on the nuances of the attributes or the relationships between classes.

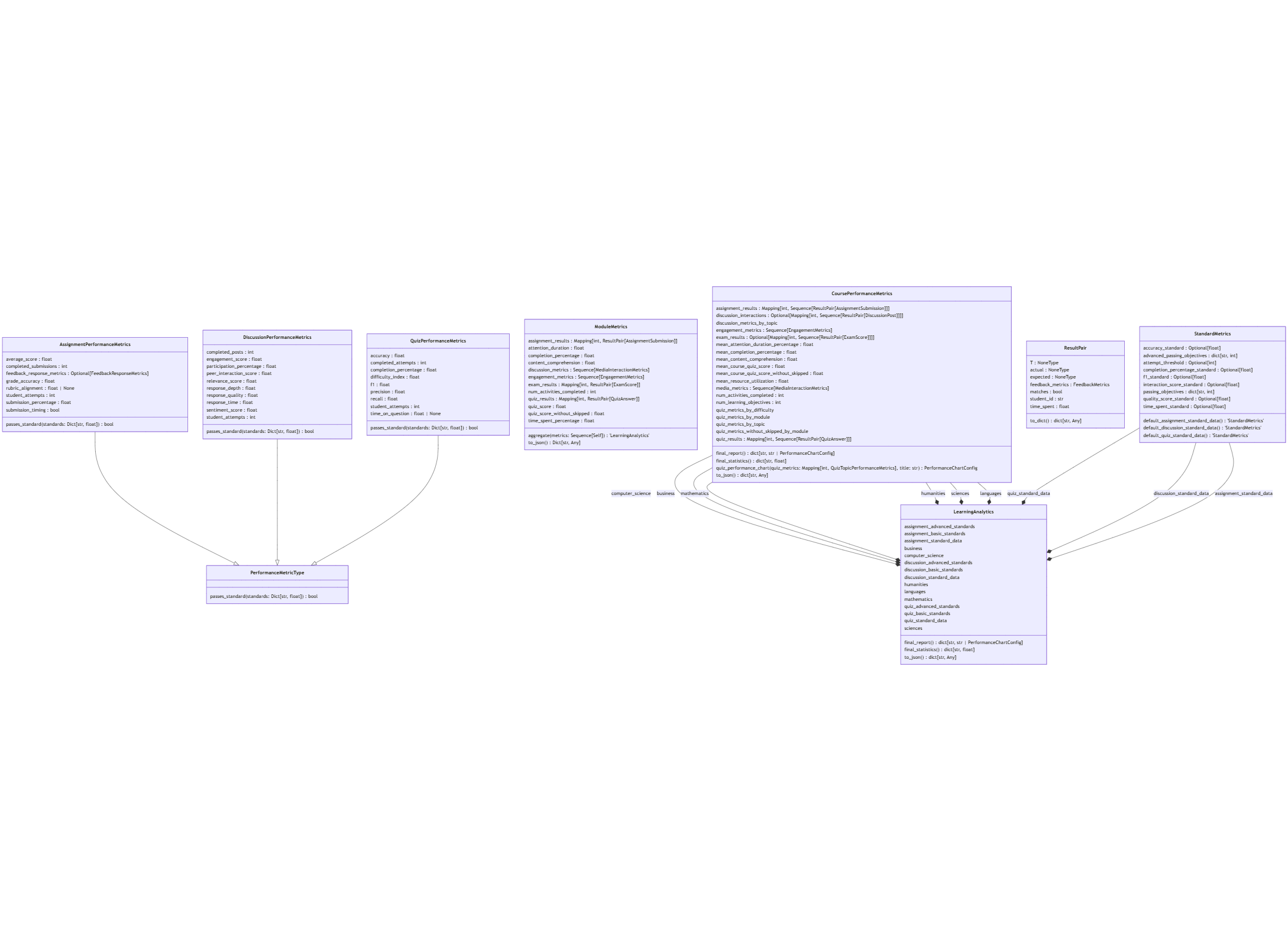

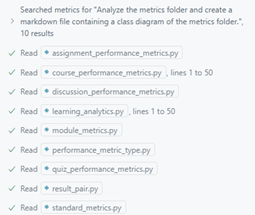

Enter GitHub Copilot Agent Mode! With our initial draft created through pyreverse, a widely used tool for generating Python class diagrams programmatically, we used Copilot to update and improve the class diagram using the draft. We also experimented with Copilot creating its own class diagram from scratch. The diagrams shown below are an example of the module diagram we were creating.

pyreverse Class Diagram

The html pyreverse diagram that was run on the module missed connections and attribute types and certain types were not connected to the correct model. While this was incorrect, it did give us an initial idea of what the class diagram should look like and an example for Copilot to use when generating its own class diagram. We converted the html diagram to markdown and then set on using Copilot to create an updated version.

Testing Prompts, Testing Models

Several diagrams were generated using the GPT4o and Claude Sonnet 3.7 Thinking models, with and without including the pyreverse diagram as context:

- GPT4o with pyreverse diagram

- GPT4o without pyreverse diagram

- Claude Sonnet 3.7 Thinking with pyreverse diagram

- Claude Sonnet 3.7 Thinking without pyreverse diagram

Two prompts were used to create an initial diagram with these models:

Basic Prompt:

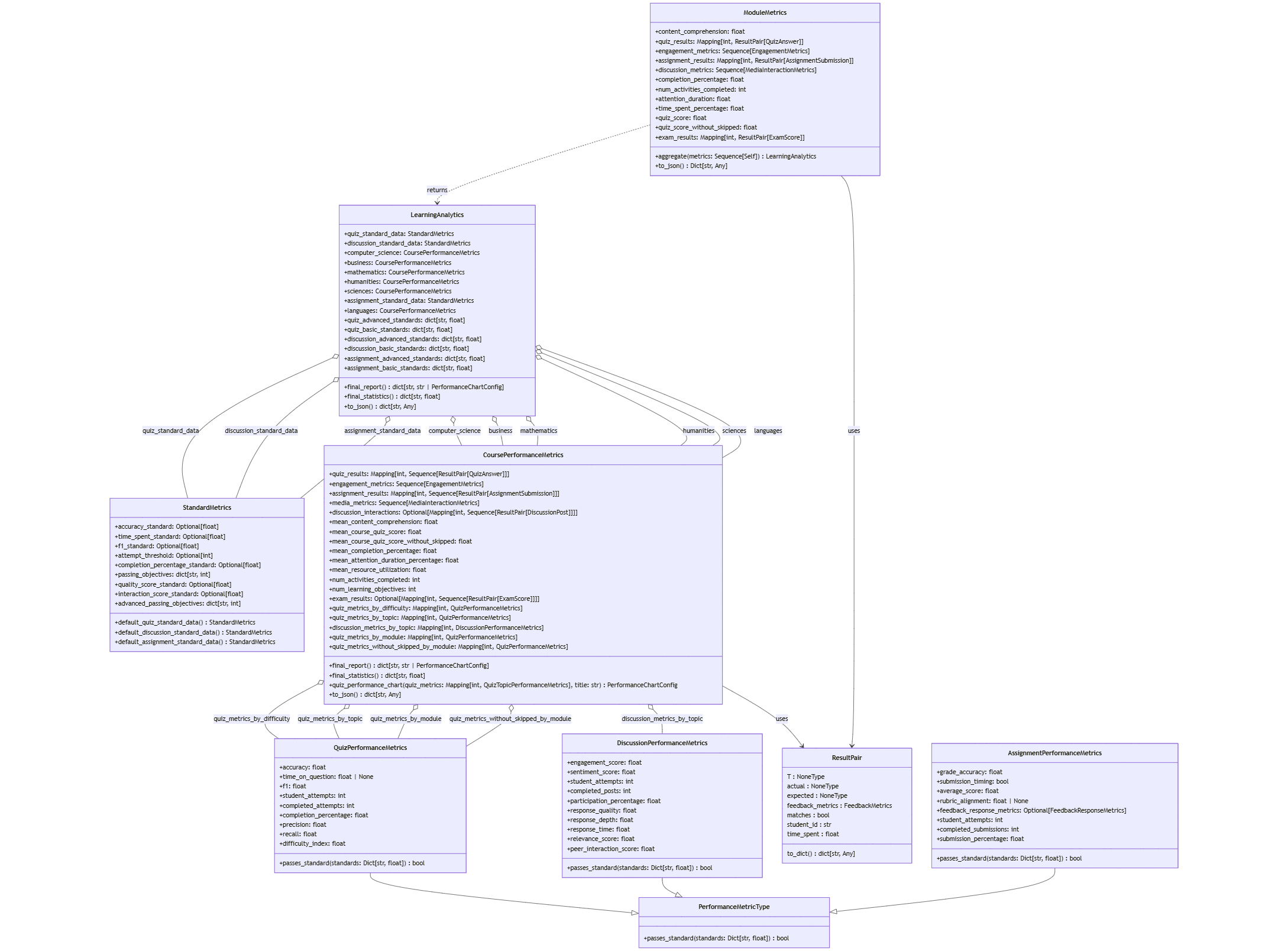

Analyze the metrics folder and create a markdown file containing a class diagram of the metrics folder. [Context provided: metrics folder]

Basic Prompt with Baseline Diagram:

Analyze the metrics folder and create a markdown class diagram of the metrics folder. Use [file containing pyreverse diagram] as a reference, noting that the diagram may not be entirely accurate. [Context provided: metrics folder, file containing pyreverse diagram.]

Creating finished diagrams took multiple iterations and edits. Different approaches were needed to create a better class diagram. The following graphs show the initial version of the graph.

GPT 4o Class Diagrams

The initial class diagram created by GPT 4o did partially recreate the classes and connected some relationships but did miss a lot of attributes. This may be due to the limited context that it pulled from; the Copilot agent only read a few lines of each file, which may have left some gaps.

When GPT 4o used the pyreverse class diagram as context the resulting diagram updated some of the missing attribute types from the original pyreverse diagram but did not add any new relationships. The result seemed to closely resemble the pyreverse diagram with minimal changes.

Claude Sonnet 3.7 Thinking Class Diagrams

The Claude Sonnet 3.7 Thinking diagram correctly added all the attributes and relationships between classes. This may be because Copilot read the entire file for each class, which led to a more accurate diagram. However, it did not add more detailed relationships compared to the initial pyreverse diagram. To add this, we needed to be more specific about the relationships that we wanted to see.

The Sonnet diagram with the pyreverse diagram as context updated all of the attributes and connected the classes correctly, as Copilot had both a relevant example to base the diagram on and was able to pull in all the files as context. However, the new relationships drawn did not specify what attributes from one class are a type of the other class and instead labeled the new relationship paths as “uses” or “contains”.

We later selected an updated version of this graph for our documentation shown below, as it required only minor edits compared to the other diagrams generated.

Findings

Copilot can be a great tool to get a head start in building class diagram visualizations; however it’s important to validate the results thoroughly to ensure accuracy. The following strategies can help you refine your initial results:

Start with an Example

Be more specific with the desired results of your diagram. Copilot did much better when it started with an example it could pull from.

Context Matters

Some models may only retrieve partial context of each file, while others might read too much – both can result in a subpar result. When reading through the chat logs or output, make sure that Copilot is reading the entire file or context when generating the diagram and reading the files you need.

Experiment with Different Models

The Claude Sonnet 3.7 Thinking model worked best for generating class diagrams, while GPT 4o needed more instruction. While the Claude models would be our recommendation for this task, continue to test out other models. As newer models get released, they may be even more advanced at creating visualizations.

Consider the Diagram Format

The choice of starting from a graphical tool like pyreverse versus a text-centric format like Mermaid Markdown may have impacted the results. For example, Mermaid Markdown could provide clearer context for models like Sonnet, potentially improving accuracy. GPT-4o may still face context limitations, but Sonnet might benefit from the text-based approach.

After creating your draft diagram, you will still need to review it extensively to ensure accuracy.

Use-Case 3: Creating Data-Viz Code

When used in the right way, using AI to generate code saved us a huge amount of time, making some activities at least twice as fast. When used in the wrong way, we actually found that it made some activities at least twice as slow.

Where AI-Generated Code Sped Us Up

We found that using Copilot to help generate Python data visualization or plotting code worked really well, and we have a few ideas why:

- Data visualization code is syntax-heavy.

- Producing plots can be one of the most time-consuming aspects of a project. Ask anyone who has nearly missed a deadline for a paper because producing figures took way longer than expected!

- There are so many plotting libraries out there, which are always evolving e.g. matplotlib, seaborn, plotly, plotnine (ggplot2), each with different syntax. This makes it hard for data scientists to keep up with all the syntax.

- The work is often tedious: e.g. looking up RGB colors, specifying chart type (“hist”, “barh”), making subplots fit a page.

- Plotting code is very common and standard, and sites like Stack Overflow are full of questions and answers. This provides plenty of training data for AI models.

- In our project, the data exploration and visualization (viz) code was separate from the main codebase. This meant we were essentially doing “greenfield” coding: generating new code from scratch.

- We already have years of expertise in data viz so this accelerates us tremendously. But, Copilot is not going to teach somebody how to explore data. We believe that the biggest gains to engineering productivity occur when AI is leveraged by deep experts who are working together across disciplines on really challenging tasks. In contrast, there won’t be productivity gains from a developer naively asking AI to perform medical diagnosis.

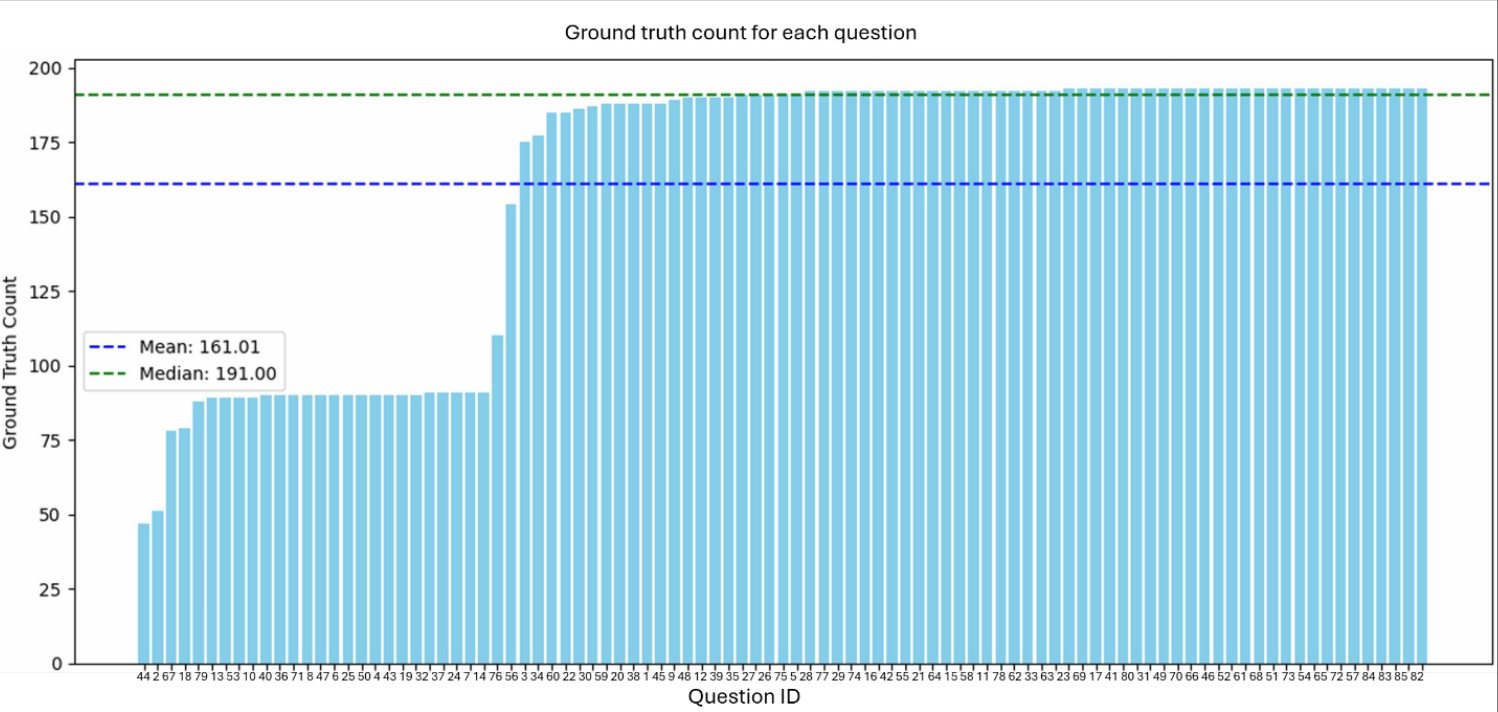

This is the type of data visualization plot that we created with Copilot. It shows a count of ground truth data for each of our Question IDs.

Data exploration and visualization is often an iterative process as you make data discoveries, which suits prompt engineering well. This is how we iteratively refined the prompt to create the plot:

Create a pyplot bar chart of the dataframe df. Group the data by the “question ID” column to count the total number of ground_truth. Plot these counts against the question ID.

… Then, sort the questions by ground truth counts

....Sort ascending

.....Change the color to light blue

……Find the median and mean of the ground truth count across all questions. Add these values as horizontal lines to the plot. Add a legend.

…….Add the following title: Ground truth count for each question

……..Rotate the x-axis labels so that they are horizontal

………Add documentation for this function Here is the kind of code that is produced with this prompt, after human-in-the-loop editing and review:

def plot_ground_truth_count_per_question(

df: pd.DataFrame

) -> None:

"""

Plots the count of ground truth values for each question in the given assessment.

This function groups the input DataFrame by the "question" column and calculates the count

of non-null values in the "ground_truth" column for each question. It then creates a bar plot

to visualize these counts, with horizontal lines indicating the mean and median ground truth counts.

Parameters:

df (pd.DataFrame): The input DataFrame containing the data. It must include columns

"question" and "ground_truth".

Returns:

None: This function displays the plot but does not return any value.

Notes:

- The x-axis of the plot represents the questions, while the y-axis represents the count

of ground truth values.

- The plot includes horizontal dashed lines for the mean and median ground truth counts

to provide additional context.

- The questions are sorted in ascending order based on their ground truth counts for better visualization.

Example:

plot_ground_truth_count_per_question(df=my_dataframe)

"""

# Group by 'question' and calculate the total count of non-null values in the "ground_truth" column

ground_truth_count = (

df.groupby("question")["ground_truth"]

.apply(lambda x: x.notnull().sum())

.reset_index(name="ground_truth_count")

)

# Calculate the mean and median ground truth count

mean_ground_truth_count = ground_truth_count["ground_truth_count"].mean()

median_ground_truth_count = ground_truth_count["ground_truth_count"].median()

# Sort the questions by ground truth count in ascending order

sorted_ground_truth_count = ground_truth_count.sort_values(

by="ground_truth_count", ascending=True

)

# Create a bar plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 6))

ax.bar(

sorted_ground_truth_count["question"].astype(str),

sorted_ground_truth_count["ground_truth_count"],

color="skyblue",

)

# Add horizontal lines for mean and median

ax.axhline(

mean_ground_truth_count,

color="blue",

linestyle="--",

label=f"Mean: {mean_ground_truth_count:.2f}",

)

ax.axhline(

median_ground_truth_count,

color="green",

linestyle="--",

label=f"Median: {median_ground_truth_count:.2f}",

)

# Add title and labels

ax.set_title(

f"Ground truth count for each question "

)

ax.set_xlabel("Question ID")

ax.set_ylabel("Ground Truth Count")

ax.tick_params(axis="x", rotation=90)

# Add legend

ax.legend()

# Show the plot

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show() Creating plotting code like this turned out to be a huge time-saver, and it did a more thorough job of documenting the function than any developer, would who would have to type all of that out.

Where AI-Generated Code Slowed Us Down

Some AI-generated code worked poorly in certain context:

Brownfield coding: Integrating changes into a large, complex, and pre-existing codebase.

Core code modifications: If a new developer joins midway through a project, there is no way to add or modify code without getting to know the existing code base. It takes time to understand how the code is organized and designed, what it achieves, why and how it achieves its functionality.

Elegant changes: Updating a class or function in a way that maintains the project’s design patterns requires knowing where and how to change it, and not just knowing what to change.

When AI is used to add or modify functionality in an unfamiliar codebase, it can produce code that works but is inefficient or redundant. For example, instead of locating the optimal place to modify an existing routine, Copilot might duplicate logic, creating maintenance headaches and increasing the risk of bugs. In one case, Copilot proposed over 400 lines code in Python to solve a problem that an experienced developer solves in just 200. By the time the issue was diagnosed and corrected, the task took roughly twice as long.

For new developers, using Copilot in Agent mode to make changes proved more beneficial than using Ask mode to simply query the codebase. Agent mode accelerated onboarding and allowed contributors to implement features more quickly. However, even with this advantage, the generated code did not always integrate cleanly or follow the project’s design conventions. While Agent mode reduced friction, it still required careful human review and refactoring to ensure elegance.

The takeaway: AI tools can accelerate progress, but do not replace deep domain expertise. For those who already understand the system, AI can be a powerful partner. For those still learning it, AI may speed up experimentation but can also amplify inefficiencies if used without careful oversight.

Use-Case 4: Creating Demo Video Scripts

In fast-moving technical projects, demo videos often become an afterthought, rushed together before a presentation or stitched together inconsistently by whoever has time. But when your team is onboarding developers and data scientists mid-project, those demos are not just nice-to-haves—they become critical knowledge-sharing assets.

By applying HVE principles, we dramatically improved this process. Treating demo scripts as first-class, reusable artifacts and leveraging AI tools like Github Copilot, we transformed demo creation from a recurring bottleneck into a strategic accelerator.

Challenge: Demo Fatigue & Onboarding Friction

As our project progressed, our team grew rapidly. Engineers and data scientists were onboarded continuously, often mid-sprint or deep into project cycles. While this scale-up was necessary, it surfaced a recurring challenge: onboarding friction.

Each new team member required context on architecture, data flows, tooling, and key design decisions. In the absence of structured onboarding materials, this knowledge was transferred informally through repeated 1:1 walkthroughs, impromptu screenshares, and scattered documentation. This resulted in demo fatigue, where senior engineers and technical leads found themselves walking through the same workflows, and code snippets over and over, often under tight timelines.

Beyond the time drain, this process led to fragmented and inconsistent knowledge transfer:

- Onboarding timelines stretched longer than expected.

- Demos were often assembled at the last minute and lacked narrative cohesion.

- Important nuances and implementation details were lost or misunderstood.

This ad hoc approach made it difficult to maintain alignment across roles and disciplines. Team members onboarded later had a different understanding of the system than those who had been present from the start. Because these knowledge gaps were hard to detect until they surfaced as blockers or rework, they quietly eroded both velocity and quality.

We needed a consistent, efficient, and reusable way to scale knowledge.

How to Apply HVE to Demo Video Creation

We began to rethink demo creation through the lens of HVE: progress that is both fast and intentional. Rather than treating demos as throwaway tasks at the end of a sprint, we applied the same principles we used in production software: clarity, structure, reusability, and rapid iteration.

Using AI to Draft, Refine and Accelerate

GitHub Copilot became invaluable in helping us go from outline to full script rapidly. Because Copilot could understand the structure of our codebase and documentation, it helped us generate demo scripts that referenced real endpoints, functions, and workflows. This not only sped up demo script creation but also increased the accuracy and relevance of what we were showing.

Modular Scripts for Different Audiences

One demo doesn’t fit all. A walkthrough that works well for engineers—highlighting code paths, technical design, and dependencies—might overwhelm business stakeholders looking for high-level insights or impact. Therefore, we modularize our demo video scripts, creating swappable sections in demo videos that are tailored to specific personas: data scientists, product managers and executives. With a few small adjustments, we could reuse the same core content to serve multiple audiences with minimal additional effort.

Grounding Demo Videos with Real Code, Not Pseudocode

Rather than relying on mockups or pseudocode, we wrote demo scripts that pointed directly to live code, data, and outputs. This made our demos far more useful as learning tools for new team members and as trustworthy narrative for stakeholders. When demos reflect production behavior, they double as validation tools and confidence boosters.

How to Write an Effective Prompt for Technical Demo Script Creation

Clarify the Purpose of the Demo

Clearly articulate what the demo is meant to achieve. Is it showcasing a new feature or explaining a technical concept? A clear purpose will keep the narrative focused and make the demo more impactful.

Define the Target Audience

Clearly identify the intended audience for the demo. Is it designed for engineers, data scientists, product managers, or business leadership? Understand their level of technical fluency and tailor the depth accordingly. Should the demo focus on detailed implementation, architectural insights, UX, or a high-level overview? This clarity ensures the content is relevant, engaging, and effective for its intended viewers.

Specify the Desired Format and Tone

Clearly define how the demo should sound and look. Should it be professional, conversational, or instructional? Setting expectations for tone (e.g., formal versus casual) and format (e.g., step-by-step tutorial versus narrated walkthrough) helps ensure the output matches your target audience and use case.

Reference Relevant Code and Assets

If using a code-aware AI tool like GitHub Copilot in agent mode, make sure to explicitly reference any relevant files, modules, or repositories. Providing this context allows AI to generate more accurate and integrated outputs, aligned with your actual codebase. This was one of the most valuable contributions from AI, because looking up specific files to reference in a demo can be very time consuming when done manually.

Make it Modular

Structure your demo scripts into clear, topic-based sections. This improves navigability for different audiences, allows viewers to focus only on the segments most relevant to them, and makes your scripts easier to update, reuse, and repurpose.

Iterate with Feedback

Share early drafts with both human collaborators and Github Copilot, using them as secondary critics to spot gaps and inconsistencies. Copilot can provide rapid, objective reviews while humans contribute to contextual and audience-specific insights. Iterating with feedback from both sources not only strengthens the script but also surfaces blind spots. It ensures that the final draft of the demo resonates with your target audience and delivers its intended value.

Example Prompt Template

Prompt:

You are helping me create an expert technical demo script for a [web app / ML model / API / product feature] designed for [brief description of the project or functionality].

Please generate a script outline and then fill in each section with sample narration, assuming this will be read aloud over a recorded screen demo.

Audience: [e.g., junior developers, technical PMs, data scientists, engineering leadership]

Objective of the demo: [e.g., explain how the new search endpoint works; show how to fine-tune the model; demonstrate authentication flow]

Code context: The code is hosted in a GitHub repo. The relevant files are:

- “/api/search.py”

- “/utils/vectorizer.py”

- “/demo/client_test.ipynb”

Goals for the demo script:

- Keep it under 5 minutes

- Reference real code (avoid pseudocode)

- Include a live interaction or code execution moment

- Make the script modular so parts can be reused or reordered

- Use natural but informative narration tone Takeaway

By embedding demo creation into the engineering workflow and treating it as a repeatable, AI-powered process, we increased clarity, reduced ramp-up time, and enhanced the overall quality of technical communication. This allowed our teams to stay aligned, move faster, and deliver demos that were impactful.

Conclusion

During development of an AI system, we intentionally explored how we could use Copilot to improve our productivity and strive for Hyper-Velocity Engineering. We made impressive gains when it came to writing and testing code documentation as well as creating class diagrams, data visualization code, and scripts for demo videos. The characteristics of these tasks that make them well suited for AI assistance is that they are time consuming (e.g. writing documentation), tedious (e.g. aligning plots on a page) and require condensing a vast amount of information (e.g. documenting relationships between classes or identifying gaps in documentation).

We also found that the expertise of the developers who were using AI assistance was key. For an experienced data scientist, AI assistance with plotting is a great productivity boost. For an engineer who already understands the code-base, AI assistance with documentation is a huge help.

However, if you don’t take the time to understand the code and naively rely on Copilot to add a new feature, the results could be low quality. We saw that although some AI generated code functionally achieved what it needed to and passed unit tests, the code was inefficient because it duplicated logic, was far longer than it needed to be making it hard to maintain, and did not follow design patterns that had already been established in the code.

Lastly, we found the human-in-the-loop and essential part of success. All content generated by AI had to be thoroughly reviewed, edited, iterated on, and ultimately our expert judgement needed to be applied.

Our key takeaway is that AI development can be sped up significantly when we prioritize engineering quality and amplify human expertise.

Attribution

Featured image is a photo by Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash.

About the Authors

Destiny Hillis is a software engineer based in Boulder, Colorado. She specializes in creative AI solutions and enjoys exploring innovative approaches to problem solving. Outside of work, she pursues her passion for vintage fashion and sewing, enjoys reading, and cares for her five dogs (yes, that’s too many dogs).

Rachel Johnson is a software engineer based in San Francisco, CA. She enjoys collaborating with others to create practical solutions to complex real-world problems through technology. Outside of work, she loves to travel, crochet, and go for walks with her dog, Potato.

Tempest van Schaik is a Principal Data Scientist based in Washington, D.C. She has a PhD in biomedical engineering and specializes in applying machine learning to healthcare. She is passionate about developing AI solutions that are responsible, safe, reliable, robust and human-centered.

Yvonne Radsmikham is a software engineer based in the Bay Area, California. She specializes in building AI-powered healthcare solutions. Outside of work, she’s usually chasing elevation — mountaineering, climbing, or just spending as much time outdoors as possible.