In our previous post “Reinventing how .NET Builds and Ships”, Matt covered our recent overhaul of .NET’s building and shipping processes. A key part of this multi-year effort, which we called Unified Build, is the introduction of the Virtual Monolithic Repository (VMR) that aggregates all the source code and infrastructure needed to build the .NET SDK. This article focuses on the monorepo itself: how it was created and the technical details of the two-way synchronization that keeps it alive.

Up until recently, the .NET SDK has been built from an aggregation of build artifacts of dozens of repositories. These artifacts flowed down the repository tree where they were stitched together at the end to produce the final .NET SDK. This approach has served us well for many years, but it has also introduced significant complexity and maintenance overhead. Since .NET 10 Preview 4, we have instead been building the .NET SDK from a single commit of a monorepo.

What is The Virtual Monolithic Repository

The Virtual Monolithic Repository (VMR) is a single git repository that includes all the source code and infrastructure needed to build the .NET SDK. You can find the VMR on GitHub at dotnet/dotnet. In reality, it is mostly an aggregation of several dozen other standalone repositories (such as dotnet/runtime or dotnet/sdk), which we call “product repositories“. On top of that, it contains additional sources such as the build infrastructure, pipeline definitions and scripts needed to build it.

The product repositories still exist separately and are synchronized with their counterparts as subdirectories of the VMR. This is where the virtual part comes from. Changes can be made either in the product repositories or directly in the VMR. Our infrastructure then keeps these two sides synchronized by creating pull requests that carry the source changes between these two sides.

The Road to the VMR

Having a two-way synchronized monorepo was always a necessary cornerstone of the Unified Build project. Reaching this point was, however, a multi-stage journey during which we had to keep shipping.

Stage #1 – Source Build Tarball

This journey began during the .NET 6 timeframe when we were heavily investing in our ability to make .NET available in various Linux distributions such as Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, and package managers like Homebrew. To achieve this, we had to comply with the rules of the maintainers of these distributions. These tend to boil down to:

- Source code for everything, no binaries allowed

- Limited or no network access

In other words, we had to be able to hand the maintainers a set of non-binary source files which had to compile into the .NET SDK without downloading anything from the internet. We refer to this process as the Source Build.

The Source Build methodology differs from how we used to build the .NET SDK for our own releases which, before the VMR, were built from a gradual flow of build artifacts through a dependency tree of dozens of repositories.

Both processes shared the same need – the dependency flow must reach the final repository (originally dotnet/installer, later dotnet/sdk).

Then, you either collect the binaries or the sources behind these binaries and feed them into your final build.

The first iteration of Source Build would walk the commits of each repository in the tree, add the Source Build infrastructure (the logic behind the Source Build) and produce a tarball archive on-the-fly. This archive was then given to the 3rd party maintainers who built it on their systems and checked the produced packages into their package repositories.

Source Build Patches

Often, we would see that the collected sources would not successfully build from source. The build methodologies differ, and it was often too complex and expensive to discover breaks before product dependency flow completed. Sometimes this even uncovered an existing integration issue before shipping. When a Source Build break happened, a fix was to be made in one of the product repositories and propagated down the dependency tree again. This was a tedious, lengthy, costly, and error-prone process.

To alleviate the pain, we allowed checking in so-called “Source Build patches” into the last repository. These additional patches with fixes would be applied on top of the collected sources. Then we’d work the patch into the upstream original repository where the patched sources came from. Once the fixed sources flowed down the tree again, the patch could be removed – it would fail to apply on top of the collected sources since they would contain this change already at that point.

Stage #2 – VMR-lite

To make our first significant step towards full VMR code flow, we needed to move away from the tarball based approach and into a dedicated git repository. The contents would be the same as our tarball, but moving to git would involve investment in code and change management necessary for the end Unified Build VMR. In October 2022, the original dotnet/dotnet repository was created. It was codenamed “VMR-lite” and was a read-only mirror (a projection) of the sources of the product repositories.

Each time we’d merge a commit into the SDK repository, a one-way synchronization pipeline would be triggered. It walked the dependency tree, collected the commits behind all dependencies, and updated the corresponding subdirectories in the VMR.

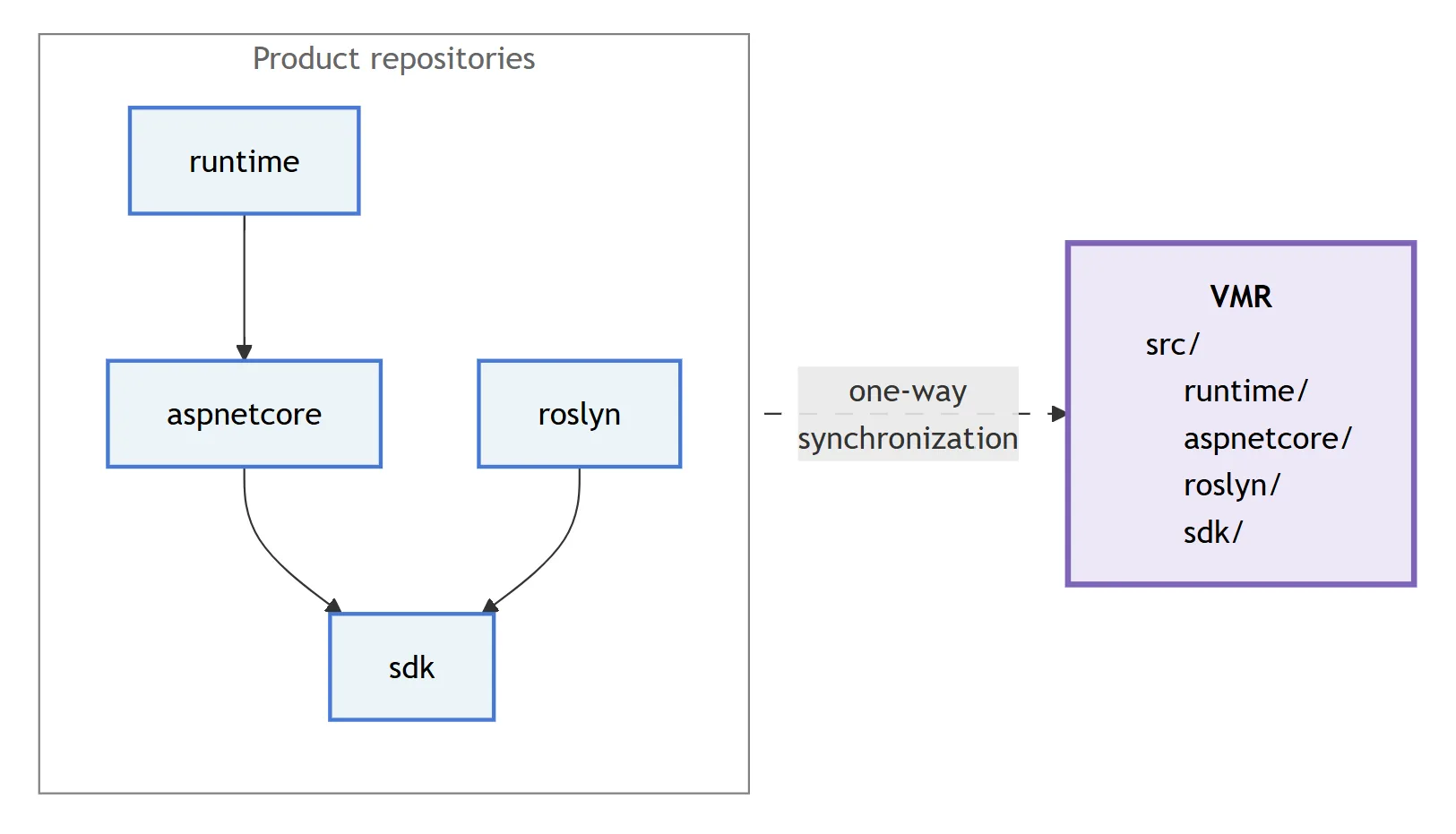

A simplified diagram showing the one-way synchronization process from product repositories into the VMR-lite.

A simplified diagram showing the one-way synchronization process from product repositories into the VMR-lite.

Undesired files such as binaries forbidden by Source Build rules were excluded during this process. The Source Build patches would be applied too.

The VMR-lite became the release vehicle for Linux distro Source Build linux-x64 starting with .NET 8 Preview 1 and continues to be used for .NET 8 and .NET 9 servicing to this day.

Stage #3 – Writeable VMR

Moving the Source Build development process onto the VMR was an important milestone and improved the workflow greatly. Analyzing Source Build breaks became much easier with VMR’s commit history. Other benefits also became apparent when we plugged the VMR into our compliance and security scanning infrastructure. However, we were aiming much higher. The ultimate goal was to unify our binary-oriented and source-based build methodologies and use the VMR as the place we can develop in and ship from all our .NET SDK builds.

There were two missing pieces in this picture. First, we must make the VMR writable. This also entails the ability to flow changes back into the product repositories. And second, the sources stop coming through the tip of the dependency tree. Instead each product repository would be synchronized directly with the VMR in a “flat” code flow model.

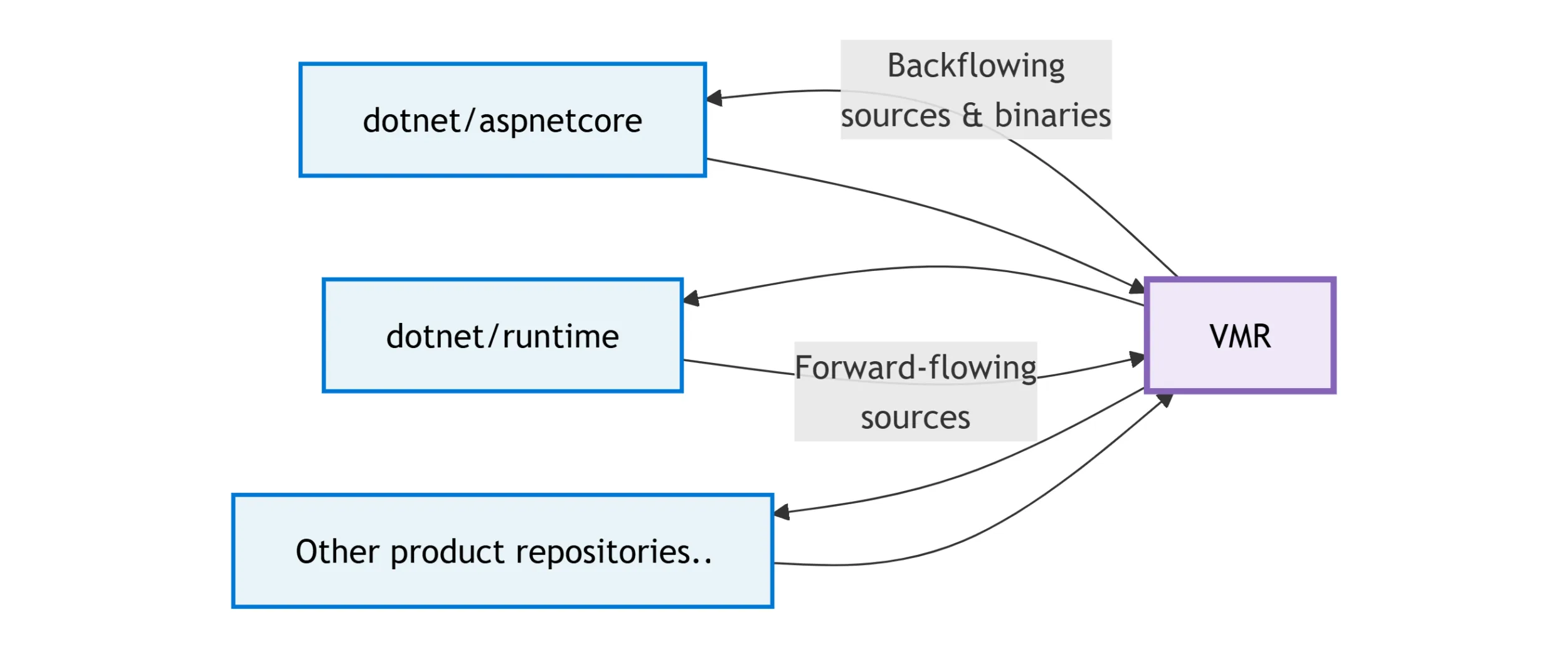

An illustration of the flat code flow structure between repositories and the VMR.

An illustration of the flat code flow structure between repositories and the VMR.

One other significant difference is in how the whole flow is realized. In VMR-lite, we have compiled the new set of sources in an Azure DevOps pipeline and pushed them into the VMR directly. Now, our dependency flow cloud service drives the flow by calculating the diffs and creating pull requests carrying the changes. This also allows us to run PR validation gates and make additional fixes in the PRs before merging the changes.

With the VMR being writable, we can start easily introducing breaking changes in a particular repository, flow the change into a VMR PR and fix the dependent code of the other repositories in the very same PR. The changes of the dependent repository directories then flow back into their respective original repositories. The backflow also contains VMR-built binaries with the aforementioned breaking change which the repositories build against.

The transition from the dependency tree to the flat flow happened with the release of .NET 10 Preview 5 and the two-way synchronized full VMR started operating then.

VMR’s Storage Model

The first decision to make was determining how to structure and create the VMR itself. We had a mix of requirements to consider coming both from our ability to meet the Source Build needs as well as our future plans for the two-way synchronization:

- To have a single, coherent commit that captures a consistent, buildable state at any point in time.

- To be able to apply the Source Build patches (a permanent delta).

- To be able to map additional paths — to project sources to other parts of the VMR such as the content of the root directory.

- To be able to exclude certain paths/files — e.g. exclusion of binaries forbidden by some Linux distributions.

- To be able to make changes to the VMR so that they could flow back into the product repositories.

We explored several ways how multiple repositories can be aggregated into one:

- Git Submodules

- Git Subtree

- Subrepo

- A custom process

Upon closer investigation, none of these fulfilled all our requirements and so we decided to implement our own custom process which maintains the files in a single monorepository as checked-in copies of the original sources. More on the decision itself can be found in the original design.

Dealing With Submodules

Some of our product repositories already contain git submodules and need them to successfully build. Some of these are even external to the .NET Foundation. Technically, these could be kept as submodules in the VMR too. However, this conflicts with some of the requirements and goals of the VMR:

- Any given commit contains all the sources needed to build the .NET SDK.

- Source Build requires the build to happen without internet connectivity to ensure no further artifacts are downloaded in the process.

- Source Build forbids non-text-based files in the VMR.

- Being a good Open-Source citizen, we would like to upstream as many changes back into the submodules as possible.

- We would like to avoid being dependent on the external submodule remote existence long-term to assure .NET servicing needs.

The limitations above give us two options:

- We either fork all submodules, strip all non-text-based files and reference these forks as submodules in the VMR. We’d then need to keep these forks in sync with the upstreams.

- We bring submodules into the VMR as hard copies of the sources instead of preserving them as a submodule link, stripping the binaries during this process.

We considered both options and decided to go with the latter which means less friction when working with upstreams. Without the man-in-the-middle forks, we can consume new versions faster and make sure we contribute back to the upstream easier. At the same time, we have all the sources at hand always and using the VMR comes without all the complications connected to submodule usage.

Moving Changes

The core of the synchronization process is the ability to move files, or rather changes of files, between repositories effectively. Keep in mind that changes can come in different shapes. Starting with the obvious addition/deletion and content modification, a file can also have its permissions (executable bit) modified, its encoding can change or the whole file can move.

Early in the design process, it became clear that if we don’t want to implement all the nitty-gritty of these operations ourselves, we need to delegate as much to git as possible. This implied that the main vehicle of moving changes between repositories would be good ol’ patches, main reasons being:

- Patches fully encode all the different types of changes that can happen to files.

- Patches can be applied to different paths, e.g. mapping of the root directory.

- It is easy to exclude / include certain files or patterns when creating patches which allow us to filter out undesired files such as binaries.

- Patch application fails when there is unexpected content which ensures correctness of the process and safe guards against accidental overwrites.

To illustrate how this works in practice, we just call

git diff --patch --binary --relative -- <ex/inclusion patterns>We then take the resulting patch and apply it in the destination path by

git apply --cached --ignore-space-change --directory=<target dir>As discussed earlier, we keep this intentionally simple to leave as much heavy lifting connected to intricacies around file changes to git itself.

This decision has proven quite robust, apart from some minor corner cases that need special handling. For example, git apply limits the maximum size of a patch to <1 GB.

To work around this limitation, we detect it and split the patch recursively into smaller chunks.

Tracking the Sources

Since it was obvious that the synchronization will involve patches, the next step was figuring out how to keep track of which sources have been synchronized where.

To track what is inside the VMR, we maintain a manifest file.

This file contains the commit SHAs of all product repositories that are currently synchronized in that VMR commit.

Additionally, it also remembers the SHAs of the vendored submodules.

Similarly, we also track the last synchronized VMR commit in the product repositories (for the purpose of the two-way synchronization).

For that, we keep the SHA of the last synchronized VMR commit in the Version.Details.xml file which we already use for tracking repo’s dependencies.

By git-blaming the tracking data, we can figure out which commit of the counterpart side was synchronized to the current repo when. This is enough to calculate how code flowed between the two sides over time. We use this later in the algorithm to determine the set of last flows and their directions. The why’s and how’s of this will be covered in the following sections.

This decision has worked quite well for us so far but there were some challenges too. To name one, it can lead to erroneous situations when a repository decides to merge its own branches between each other and accidentally overwrites the tracking data. It can also be hard to “reset” the tracking data when needed as changing the tracking data affects the git blame results. We are currently exploring more robust ways such as using git notes to store the data outside of the main source tree.

One-Way Synchronization

As described earlier, the VMR-lite was a read-only projection of the product repositories. Some content was excluded from synchronization such as binaries rejected by our Source Build partners. Additional content could be mapped to different paths such as the root directory which came from within dotnet/installer. Lastly, the Source Build patches were applied on top of the synchronized content.

To configure these synchronization rules, the VMR contained a configuration file that looked something like this:

{

// Each mapping represents a product repository with its own content-exclusion rules

"mappings": [

{

"name": "runtime",

"defaultRemote": "https://github.com/dotnet/runtime",

"exclude": [

"tests/**/*.dll"

]

},

{

"name": "aspnetcore",

"defaultRemote": "https://github.com/dotnet/aspnetcore",

},

// ...

],

// Example of additional mapping of content to the root of the VMR

"additionalMappings": [

{

"source": "src/SourceBuild/content",

"destination": "/"

}

],

// Path to the directory containing Source Build patches

"patchesPath": "src/installer/src/SourceBuild/patches"

}The synchronization process itself is a basic building block not only for the VMR-lite but later also for the full two-way synchronization. The process is complicated by the fact it must handle changes of the submodules as well as Source Build patches. It’s also important to note that the configuration file that dictates the synchronization rules can also change. This means that both Source Build patches and the additionally mapped content can change during the process, need to be correctly stripped away and then re-applied back.

With everything we’ve learned so far, we can now summarize the process in the following steps:

- Revert all Source Build patches applied in the VMR.

- Determine the set of commits representing the repository tree.

- For each repository that needs an update:

- Revert additionally mapped content coming from this repository.

- Create a patch in the original repository between the last synchronized commit and the new commit:

- The commit range equals the previously synchronized commit (from the manifest file) and the currently synchronized commit.

- Follow exclusion rules.

- Ignore submodule changes.

- Split the patch if it is too large.

- Apply the patch to repo’s subdirectory in the VMR.

- Check repository’s submodules:

- Create a patch for changes in each submodule following same pattern as above (recursively).

- Apply these patches to the respective submodule directories in the VMR.

- Apply changes of additionally-mapped content coming from this repository.

- We again create and apply patches for given paths and commit ranges.

- Update the tracking information in the manifest file.

- Apply Source Build patches on top of the synchronized content.

Good, now we’re able to move changes from a product repository into the VMR.

Two-way Synchronization

The end goal of this whole effort is the two-way synchronization between the VMR and the product repositories. As mentioned already, this would no longer be achieved by a pipeline pushing changes directly into the VMR. Instead, our code flow service would create so-called “code flow pull requests” carrying the changes. When creating the pull request branches, we will stick to our weapon of choice for moving changes – patches.

Though the basic building blocks of the process remain the same, the whole problem becomes considerably more complex. Outside of making sure the right changes materialize in the right way on the other side, we must also account for the flows happening in parallel, often at varying frequencies. In other words, it can very well happen that changes keep flowing in one direction at a daily cadence while the pull request in the other direction gets blocked by an integration build break and takes days, or even weeks, to be merged. The code flow algorithm must be able to understand these situations and make sure conflicts surface only when an actual conflicting changes were made.

Being correct is not everything either. The pull requests must also convey what changes are included, where they come from and attempt to offer guidance when conflict resolution is needed. When flowing millions of lines of code monthly across dozens of repositories, chaos is easily introduced and developers must be equipped with the right tools and information so that they can make the right decisions and stay on top of everything. Lastly, we also need to understand the holistic state of the system to identify interruptions in the flow, long-living PRs, and other potential bottlenecks. Developer experience and observability are crucial for us to be able to maintain a healthy system.

Similarly as before, we have developed a custom algorithm on which we iterated. We will walk through the evolution too to better illustrate our learnings. Hopefully, some of these can be useful for anyone trying to solve a similar problem.

Terminology

Let’s look at some of our terminology we’ll be using in the rest of this section:

- Source/Product repository – One of the current development repositories, e.g.,

dotnet/runtime. Not the VMR. - Forward flow – The process of moving changes from an product repository to the VMR.

- Backflow – The process of moving changes from the VMR to an product repository.

- Code flow – The process of moving changes between the VMR and product repositories. This is a generic term that can refer to both forward flow and backflow.

- Code flow PR – A pull request carrying the code changes that is opened as part of the code flow process. This can be a forward flow PR or a backflow PR.

Two-way Code Flow v1

The first iteration of the code flow algorithm was designed with a goal that every time we need to flow changes, we must be able to create some pull request in the target repository. This pull request must contain the desired changes but might conflict with the target branch. We will show how we later realized this was a misguided north star as it introduced some interesting problems.

The TL;DR of how the algorithm works is that we keep track of the last flows between the two sides using the tracking metadata described above. We then find the right place (commit) to create the PR branch in the destination repository from, materialize the changes on top of it and open a pull request. We must assure you that if there are conflicting changes between the two sides, these are also present in the PR. This means that the PR branch must be based on an old enough commit to bring both the commit from the source as well as the change in the destination branch into the conflicting state.

The first iteration of the code flow algorithm was used to ship most .NET 10 previews as well as the 10.0 release. The algorithm considers the direction of the previous flow and applies different strategies based on that. Technically, there are four scenarios to consider (forward-forward, forward-backward, backward-forward, backward-backward) but the latter two are symmetrical so we will not discuss them separately.

Flows in Opposite Directions

Let’s have a look at the more complex scenario from the two first – when we have two flows in opposite directions. The diagrams in this section use the following notation:

- 🟠 Orange – File content transformations. A file starts with content

A, andB -> Cmeans a commit changed content fromBtoC. - 🟢 Green – The previous successful flow. Shows which commit is being flown (dashed) and what the PR branch on the other side would form like (solid).

- 🔵 Blue – The current flow being discussed.

- 🟣 Purple – The diff being carried to the counterpart repository.

- ⚫ Grey – Unrelated commits that don’t affect the tracked file.

- Commits are numbered in chronological order. Points

1and2typically denote some previous synchronization.

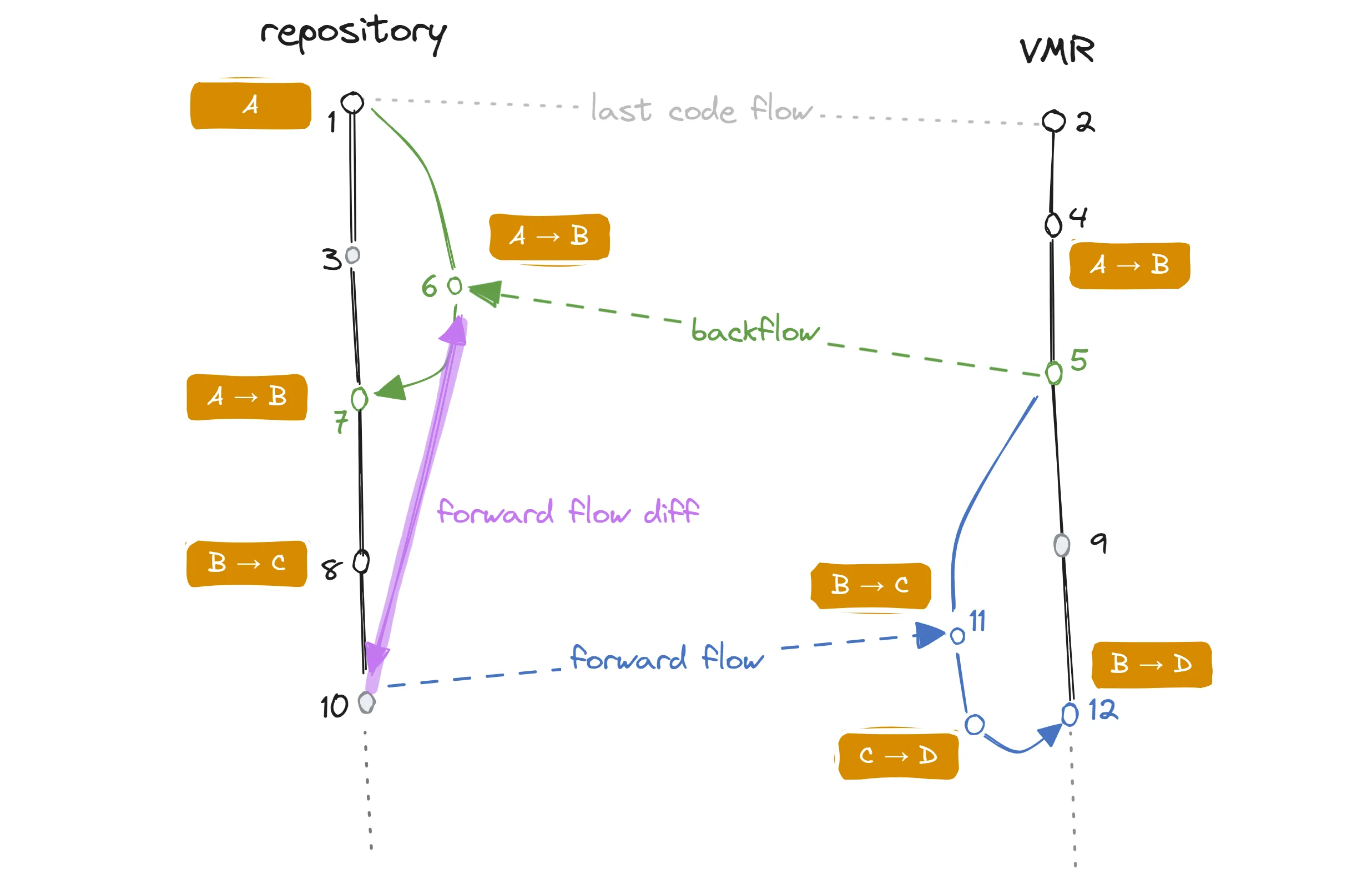

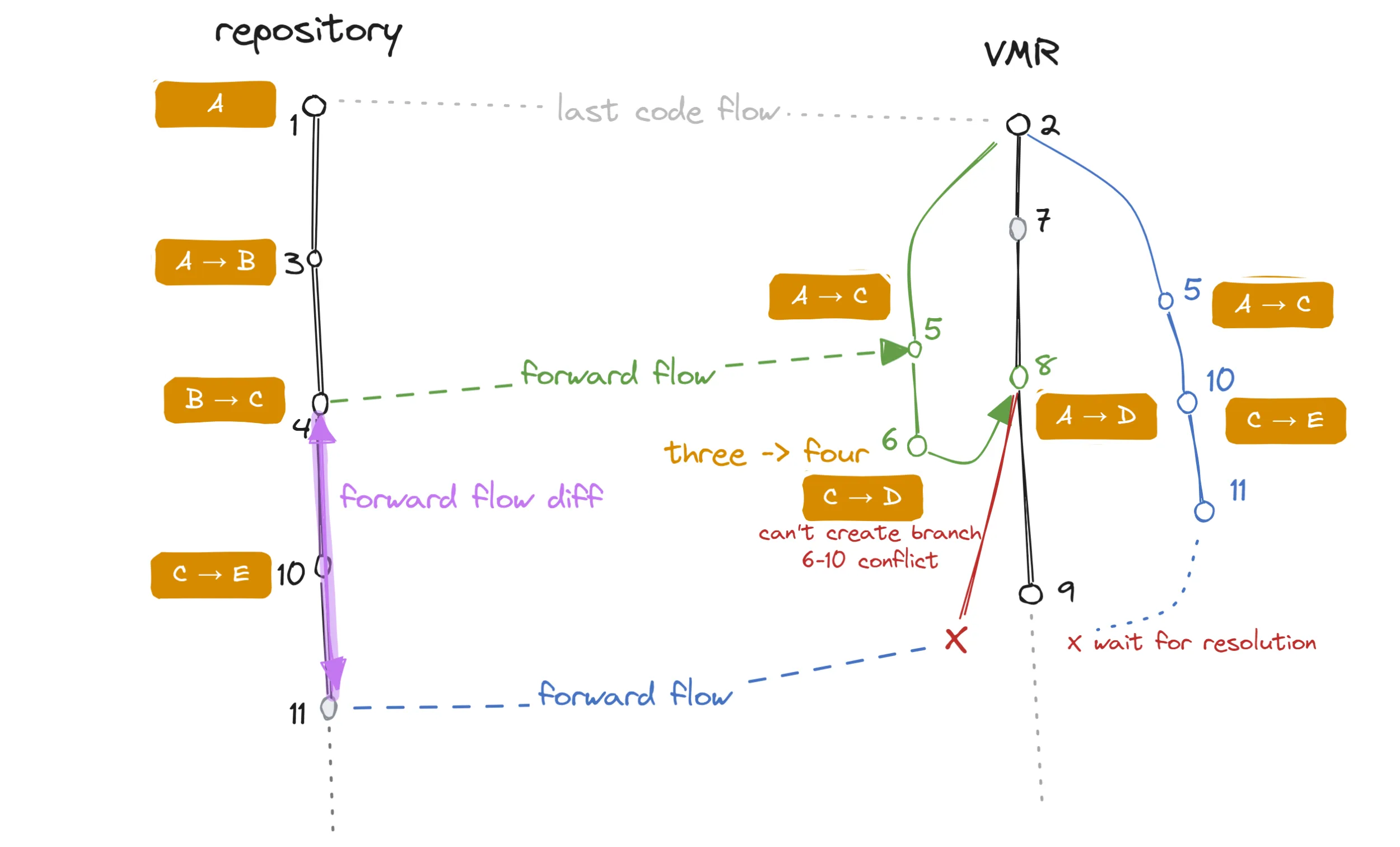

A code flow diagram showing two consecutive flows between a repository and a VMR, each in a different direction.

A code flow diagram showing two consecutive flows between a repository and a VMR, each in a different direction.

The flow of changes in the diagram is as follows:

1and2denote some previous synchronization point.4Commit in the VMR changes the contents ofAtoB.5A backflow starts at that point.6A backflow branch (green) is created in the repository. The branch is based on the commit of last synchronization (1). How this flow is created is not the subject of this diagram. Here, we are interested in the following flow. A PR from this branch is opened.7Backflow PR is merged, effectively updatingAfromAtoBin repository’s main branch.8A commit is made in the repository, changing content fromBtoC.9An unrelated commit is made in the VMR.10A forward flow starts at that point.11A forward flow branch (blue) is created in the repository. The branch is based on the commit of last synchronization’s (5) base commit. A PR from this branch is opened. An additional commit is made in the forward flow PR which changes the contents ofAtoD.12The PR is merged, effectively updatingAfromBtoD.

You can notice several features:

- No (git) conflicts appear. This is because this concrete example considers a single file that is chronologically changed from

AtoDin gradual steps. In cases where most of the changes happen in the individual repository, we expect the code to flow fluently. - The whole flow is comparable to a dev working in a dev branch within a single repository. The dev then opens a PR against the main branch (the repository in this case). Wherever there are conflicts in a single repository case, we would get conflicts here too and this is by design.

What is left to discuss is how we create the commit (11) of the forward flow branch.

We know that we received the delta from the repository as part of the commit 7 after the last backflow PR was merged.

We account for the fact that a squash merge was used and commit 6 might not be available anymore.

There could have also been additional commits on the backflow PR branch between commits 6 and 7.

The set of changes we need to flow when we are flowing commit 10 technically consists of commits 3, 6, 7, 8 and 10.

Basically, everything that happened on the repository side that has not yet been flowed into the VMR.

It is visualized as the purple diff between 10 and 6.

This diff correctly represents the delta because:

- It contains the last known snapshot of the VMR (

6) - All commits that happened in the VMR in the meantime (since the last commit) – the commits

3and7. - The other commits that happened in the VMR since the sync

8and10.

The base commit of the forward flow branch is then the base commit of the last backflow as that’s what we’re applying the delta to.

If commit 9 had conflicting changes compared to the delta, the PR would show these conflicts, and the dev would have to resolve them.

Two Flows in the Same Direction

The situation is a bit simpler when we have two consecutive flows leading in the same direction:

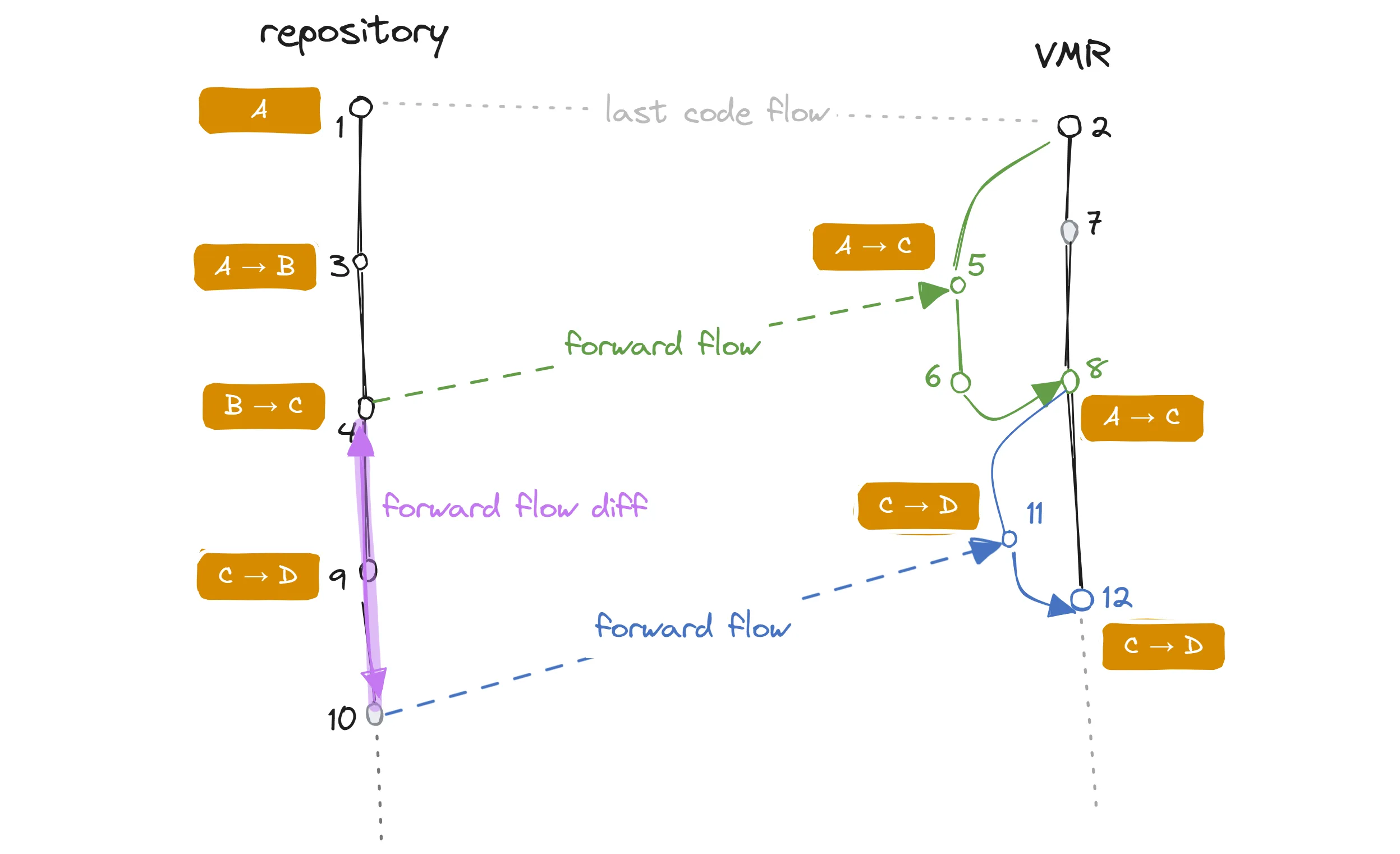

A code flow diagram showing two consecutive flows from a repository into a VMR.

A code flow diagram showing two consecutive flows from a repository into a VMR.

When we are forming the forward flow commit (10), we know that the only things that happened since we last sent all our updates to the VMR are the commits 9 and 10.

We can then just apply this new delta on top of the last forward flow commit (8).

Conflicts

A conflict is a situation when the same chunk of the same file is changed in diverging ways in the repository and the VMR at the same time. Human intervention is then needed to decide which change wins. The goal of the algorithm is to make sure that these conflicts are surfaced and dealt with before changes can flow again. However, we will show how it can matter in what exact way a conflict is introduced with respect to the ongoing code flow. We will also show how conflicts can appear even when no conflicting changes were made at all.

Let’s consider the following example where a conflict is introduced by an extraneous commit that was made in a forward flow PR:

A code flow diagram showing a conflict introduced in a code flow PR.

A code flow diagram showing a conflict introduced in a code flow PR.

In this situation, the additional commit that was made in the first forward flow PR (6) conflicts with a commit made in the repository (10). Since there was no backflow, this information is unknown to the repository side.

The follow-up forward flow is problematic because changes 10 and 11 cannot be applied on top of 8.

We are, in fact, even unable to create any commits for the PR branch at all!

In such a case the only thing left to do is to base the PR branch on the last known good commit (2) and reconstruct the previous flow (by re-applying 5 which is technically 1, 3 and 4), apply 10 and 11 on top and create a PR branch that will be conflicting with the target branch because of the 6/10 conflict.

The user would then be instructed to merge the target branch (9) into the PR branch and resolve the conflict. For those changes contained in 5 that are more or less the same as the ones in 8, git will transparently match up and only the actual conflicting files will be left for resolution.

The next backflow will then bring this resolution over to the repository.

There are countless other examples of conflicts that can occur, but these will usually manifest as conflicts in the PR. The example above is more interesting because the forward flow is unable to even create the PR branch in the first place. This is because 8 (the previous forward flow commit) contains 6 which conflicts with 10.

It’s important to note that the set of conflicting files will not only contain the problematic file but also the manifest file that tracks the last synchronized commits. This is because the manifest file was updated in commit 8 where it contains SHA of commit 4 while the PR branch is updating the same line to 11.

It is impossible for us to partially resolve this even when we know the desired content of the source manifest because git does not allow partial merge resolutions.

This means that when a real conflict forces us to rebase to an older commit, it brings trouble…

Conflicts, Conflicts Everywhere

Once we started testing the algorithm in practice, we started realizing that the real complexity lies in the dynamicity of the problem happening in a real development rhythm. Flows rarely happen in a ping-pong-like sets where changes flow back and forth nicely in a predictable manner. Instead, we must expect flows happening in both directions in parallel, on their own frequency, often taking a long time between opening and merging.

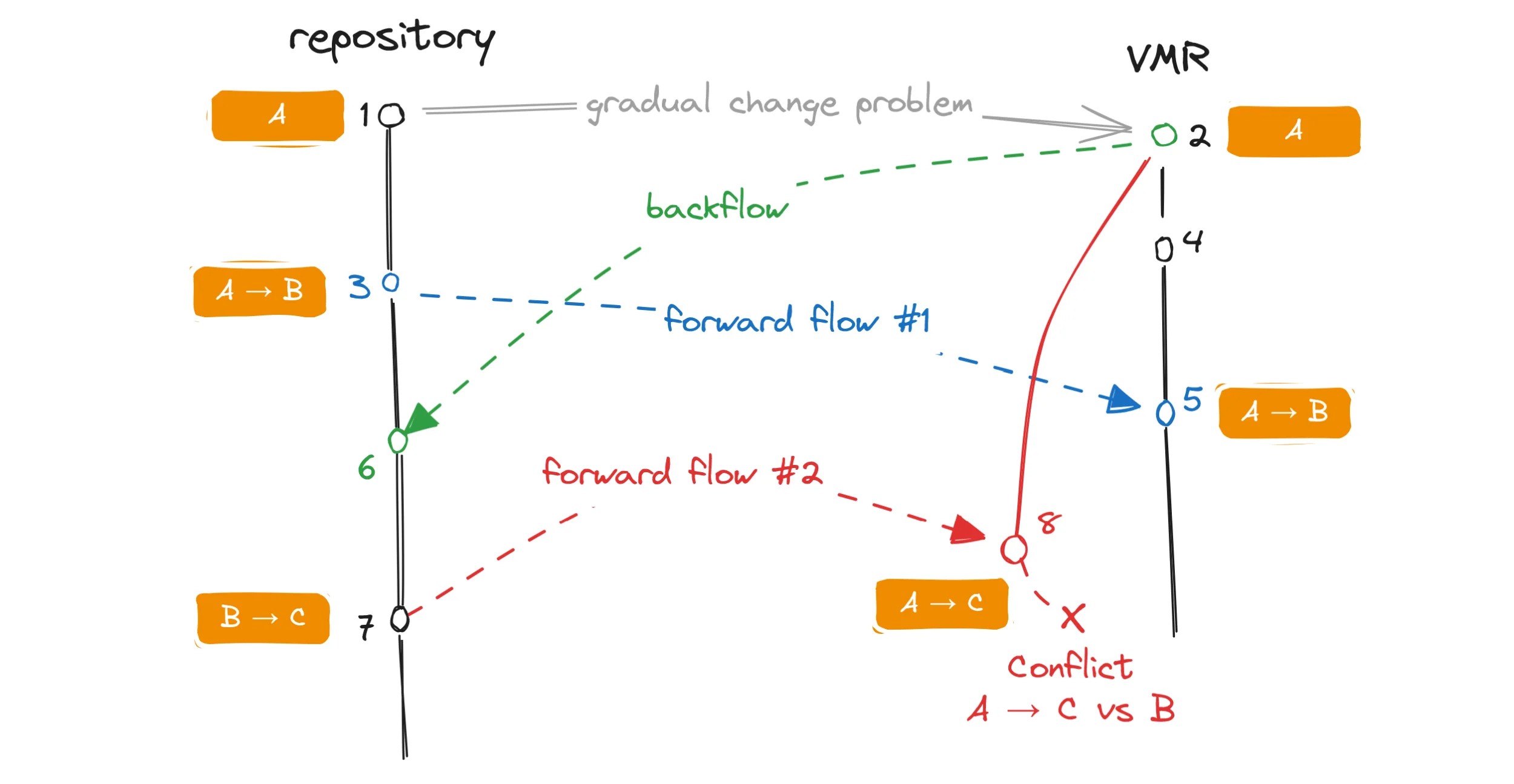

Let’s look at a scenario where a single file goes through a series of gradual changes in the source repository and while we don’t make any actual conflicting changes to it, we will still see conflicts in the code flow PR:

A code flow diagram illustrating problems arising during gradual changes of a file.

A code flow diagram illustrating problems arising during gradual changes of a file.

In this example, a file in the repository had its content gradually changed from A to B to C.

No changes were done to it in the VMR.

A forward flow 🔵 and a backflow 🟢 started in parallel and each had been successfully merged.

The forward flow 🔵 successfully updated the file in the VMR from A to B.

Now let’s look at the second forward flow 🔴 which should technically bring over the change B to C.

The second forward flow is following the algorithm of the opposite direction flow described above and its PR branch is based on the commit of the last backflow 🟢.

This effectively means that the PR branch contains the change from A to C.

However, the target branch already contains the change from A to B.

When we try to merge the PR, git sees a conflict between the change from A to C (the PR branch) and the change from A to B (the target branch) and we fail to merge the branch.

You can see on this example that even though there were no conflicting changes made to the file, the way the flows interleaved caused a conflict regardless. To address this, we can use the information about both of the previous flows – not just the last one – merge the target branch into the PR branch and resolve the conflicts programmatically as we understand the desired end state of the files. However, this only works when there’s no additional changes to the file that we don’t expect. Furthermore, when a real conflict is thrown into the mix, merging the branches becomes impossible again. That also means the user will not only have to deal with the real conflict but also with a conflict in the gradually changing file that should not be a conflict in the first place! One such file is the source manifest which changes in each flow, and which always ends up in conflict in this situation. The developer then must resolve a conflict in the tracking data themselves which is not ideal as it can easily lead to a disaster.

These situations are not rare. Workflows which introduce new files that are quickly modified in a follow-up PR are common (e.g. localization).

The Revert Problem

The problem described above, though workable, already points to some inherent limitations of the approach. The last straw that broke this camel’s back and made us rethink some of our goals was the so-called revert problem.

The idea is similar to the previously described scenario but instead of gradually changing a file, we make a change to it and later revert this change back. If we manage to flow the change separately from the revert, and the second flow with the revert also ends up in a conflict, this perfect storm prevents us from merging branches automatically and we will lose the revert completely!

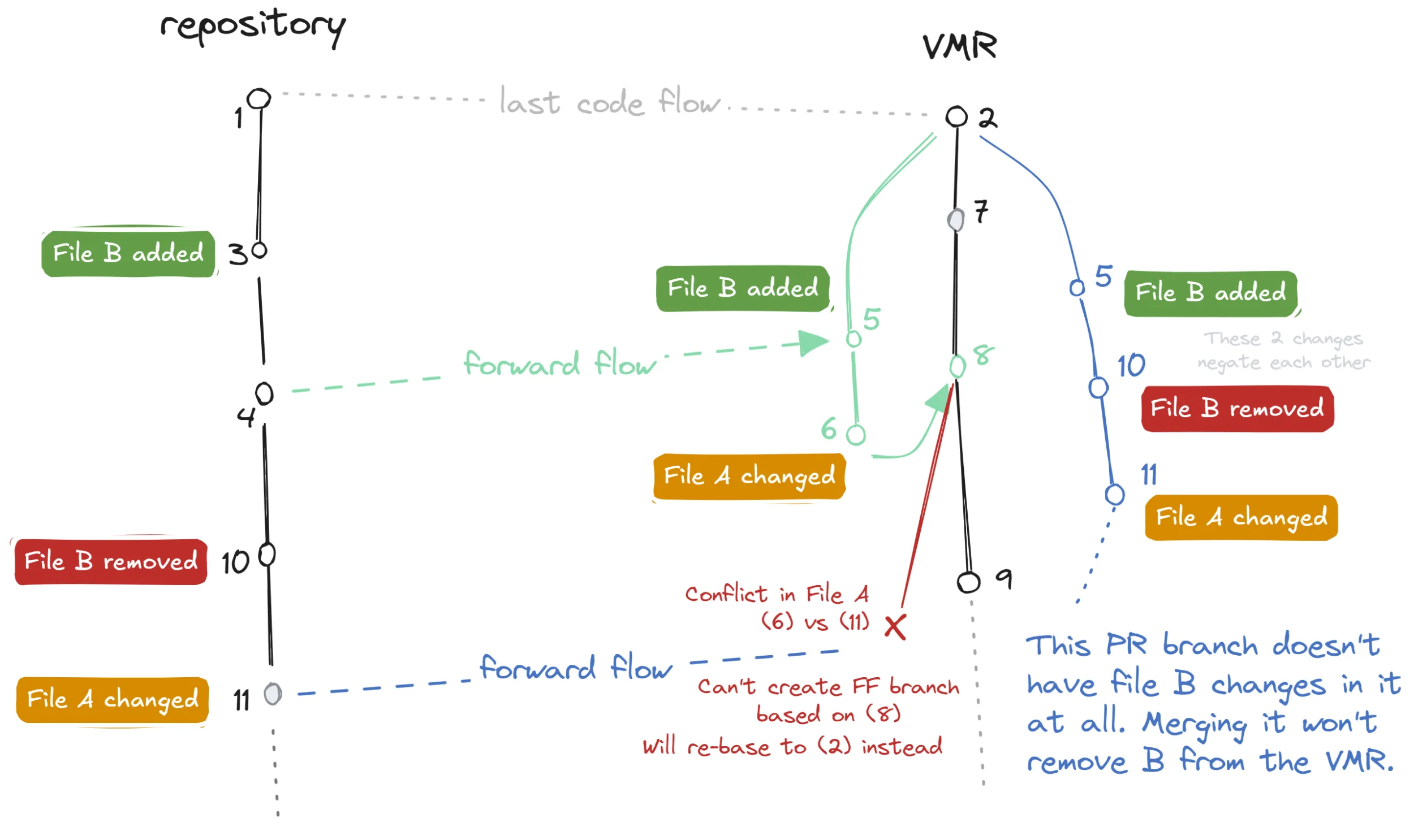

A code flow diagram illustrating a problem that arises when a file change is reverted.

A code flow diagram illustrating a problem that arises when a file change is reverted.

In this example, we can observe the following:

- File

Bis added 🟢 and then removed (reverted) 🔴, while fileAreceives unrelated conflicting changes 🟠. - The forward flow PR branch contains all three changes where the revert negates the original change which manifests as the file

Bnot changing at all. - The conflict in file

Aprevents us from basing the PR branch on top of commit8(the last backflow) and we must instead base it on commit2, while we recreate the previous flow. - Since the newly rebased PR branch now technically does not contain any change to file

B(the change and its revert cancel each other out), when we merge the PR, the revert is lost completely and the fileBstays in the VMR while it was removed from the original repository.

Furthermore, this does not only apply to full file reverts but as well to any change, however small, that is later reverted back. Scary!

Even though several conditions must click together, this can happen in practice. Specifically, we’ve seen this in cases where a temporary workaround or feature flag was introduced in the code and later it got removed again. It also happened when PRs were reverted in full in a busy repository where actual conflicts can occur frequently. Regardless, it was not acceptable for us to lose changes silently like this. Back to the drawing board!

Rebasing Our Approach

At this point, we have depleted all possibilities offered by plain branching and merging. For every workaround and idea we’d come up with, there’d be a counterexample that shatters it!

Changing the Playing Field

This led us to reconsider our goal of being able to always create a PR with some content in the target repository. Since we cannot partially resolve conflicts, the resolution must happen in a different environment than the GitHub PR UI. Can it be the dev’s local machine? Can we let the user run a command that would perform the flow locally which would bring the local repository in the conflicting state, resolve the known (non-)conflicts such as source manifest changes, and let the user deal with the actual problems?

Different Game Too

One other design guide we tried to follow was comparing how our dual-repository solution differs from having just a single repository with multiple branches.

How do our flows and git operations differ from a regular day of work in a feature branch leading to a feature PR?

In what other way do people deal with conflicts?

And when they do, how does the process look like?

This led us to explore a different approach altogether.

We’re talking about the git rebase flow.

Let’s Get Interactive

When we combine the ideas above, we arrive at a new code flow experience that is more interactive and relies on a different user intervention when conflicts arise. The new process does not look too different from a regular git rebase flow:

- The code flow service still calculates the changes the same way as before – taking previous flows into account, constructing a branch based on the last flow, etc.

- We then attempt to rebase the PR branch onto the tip of the target branch. This fails when there are conflicts and leaves the repository in a conflicting state.

- When no conflict occurs, the rebase is committed and pushed into a new PR and we’re done.

- In case of a conflict, the code flow service cannot proceed further. It instead opens an empty PR and instructs the user to perform the flow locally using custom tooling.

- The service then blocks the PR merge with a custom status check until it sees the desired changes pushed to the PR branch.

- The custom tooling fetches necessary information and performs the same code flow locally.

- Upon conflicting, it resolves any known conflicts which can be the result of flows happening in both directions in parallel as discussed above. It then leaves the user to resolve the actual conflicts.

- The user then commits and pushes the changes.

- Finally, the service validates the pushed contents and unblocks the PR for merging (it greenlights a custom status check).

- This PR shows an example of what this PR looks like.

The fact that we can resolve known conflicts partially while leaving the actual conflicts to the user is the key to success here. We don’t suffer from the revert problem anymore as we can correctly compute the deltas, using all the information about the previous flows. But since we are already on top of the target branch, we can correct any missing reverts too. We can detect missing reverts by trying to reverse-apply the last flowed change and seeing for which files this fails. That can happen only when they are missing a change.

We rolled out this new experience in December and so far, we’ve had much better experience with it. There is still one experimental improvement we’re looking into where we would not create the working branch in the target repository but rather apply the patch direcly on top of the target branch. However, this does not work out of the box in git as some operations such as modifications to files not known to git (e.g. file is modified in one side while removed in the other) will fail the application process. So far it showed that it’s easier to manifest the required changes in a working branch of the target repository first and then rebase it onto the target branch because git can work with more information from the commit graph while rebasing. However, if we managed to solve the unsupported cases, it would mean a big simplification of the process since part of the working branch creation is the previous flow reconstruction.

Present Challenges

We’ve traveled a long way, but it would be naive to think we’ve arrived at the destination. Yes, we were able to ship a dozen releases using the VMR, and yes, it has already brought fruits like allowing us to finalize on a release build earlier while being able to accept last-minute fixes in much later in the process. Surprisingly, even switching from the repository dependency tree to a flat topology did not meaningfully disrupt our day-to-day development of .NET 10. With some careful planning, we were able to make the move in mere hours. Nonetheless, it’s necessary to mention there were hiccups along the way.

Branching & Product Lifecycles

.NET is a huge platform and consists of many different products that often ship at their own cadence. Visual Studio, Aspire, .NET MAUI, Entity Framework, to name a few, have different lifecycle models and require a different rhythm. One that does not always align with .NET SDK’s. In short, there are several main groups of repositories based on their product lifecycle:

- SDK band centric – repositories such as

dotnet/sdkthat ship different variants per each SDK band. They would branch in the same way as the VMR itself, e.g.release/10.0.1xxorrelease/10.0.2xx. - Shared components / runtimes – repositories such as

dotnet/runtimeordotnet/aspnetcorethat ship components shared between multiple SDK bands. They would usually branch per major version, e.g.release/10.0orrelease/11.0. - VS centric – repositories such as

dotnet/roslynthat ship components tightly coupled with Visual Studio releases. They would usually branch per Visual Studio version, e.g.release/17.14orrelease/dev18.0.

You can read more about our branching strategy in detail the VMR SDK Bands documentation.

These differences in the lifecycle started surfacing when repositories needed to branch at separate times than the VMR which follows the SDK band centric model. The code flow algorithm was designed to handle synchronization of two branches between each other only. In practice this means that when a repository needs to start synchronizing a different branch with a given VMR branch, we must reset the contents of the VMR manually to make it match the repository. This is a complicated process as we must make sure that no changes made to the VMR are lost in the process.

Situations like the one above have happened dozens of times during the .NET 10 product cycle already as we are busy working on shipping the .NET 10.0.200 release. We are still working through this problem where we plan to detect changes in our code flow configuration and issue an automated content reset PR that tries to gracefully handle the transition.

Snapping Release Branches

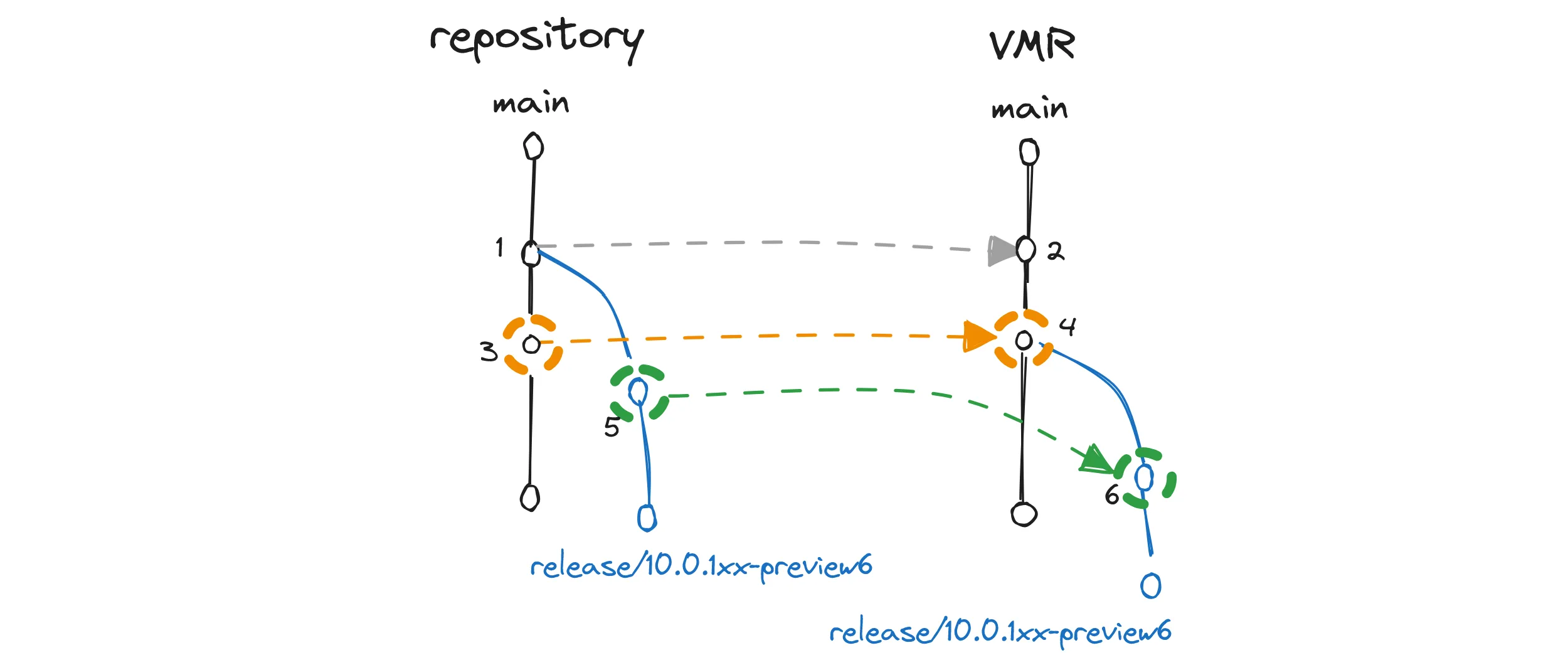

Another problematic situation can occur when we’re snapping branches for release, and each product repository would snap at their own time.

During the development of a new major .NET version (e.g., .NET 10), each month we’d snap our main development branches into the respective preview release branches (e.g., release/10.0.1xx-previewN).

Consider this case when the repository snaps its branch before the VMR does:

A code flow diagram illustrating problems arising when branches are snapped in the wrong order.

A code flow diagram illustrating problems arising when branches are snapped in the wrong order.

Notice how the commits 3 and 5 get flowed into the VMR and depending on when each repo snaps it branches, they either are or are not in a parent/child relationship.

In the diagram, they are not related in the repository while they are parent/child in the VMR.

This is obviously wrong as both can be making conflicting changes but are totally valid in the context of their own branch’s history.

We prevent such situations from being introduced by driving the snaps centrally, starting in the VMR. The VMR goes first upon which we find the latest commits in each product repository where the snap still makes sense. We then create the release branch there.

Metadata Corruption

Another challenge we’ve encountered involves the synchronization tracking data.

A common practice in the product repositories is to merge release branches between each other.

For example, changes made to the release/10.0.1xx can usually be merged into the higher band’s release/10.0.2xx branch.

During this process, the tracking metadata, if overwritten, can become inconsistent.

The 2xx branch of the repository ends up referencing a VMR commit that was synchronized with the 1xx branch.

We’re currently experimenting with using git notes as an alternative storage mechanism for tracking metadata. Git notes attach metadata to commits without modifying the commit itself, which could help us avoid some of the problems arising from having the metadata as part of the working tree.

What Was Not Covered

This article grew long very fast and for that I apologize. Nonetheless, there are still numerous related interesting aspects that would deserve more attention since they are as vital for the overall success as the synchronization algorithm itself:

- Developer experience – What all we did in terms of UX to help developers navigate code flow PRs and track where their changes are synchronized into.

- Monitoring and observability – How we track code flow state and health, detect stuck flows, or alert on issues across repositories.

- Tooling – What custom tools we built to help developers perform local code flows, resolve conflicts, and validate changes before pushing.

Let us know if you’d be interested in reading about any of these topics in more detail.

Conclusion

If you made it this far — first, thank you — and second, hopefully, you gained some insight into our journey from a tarball-based Source Build to a fully synchronized monorepo, all while keeping hundreds of developers productive across dozens of repositories, shipping monthly releases without interruption. The Virtual Monolithic Repository has become a foundational pillar of .NET’s infrastructure, enabling us to unify and streamline our build and release processes while preserving the flexibility and autonomy of individual repositories and their communities. These wins, however, come at a cost of the complexities involved in synchronizing the repositories. In case you’re embarking on a similar journey, where maybe our current setup can be but a stepping stone on a path to a full monorepo, we hope our experiences and learnings prove useful. Don’t hesitate to reach out too, this is a niche problem and we’re happy to talk!

Thanks for the article. Me dealing with a single repo/multi project was bad enough so now I count myself lucky.

The question that dawned on me with this interaction of git & tooling is how do you do integration tests such that you can make a change to some aspect of the process and run automated tests…? Do you have that setup? Is it possible? How hard is that?

Cheers,

Graham

I would say that testing this is comparatively easier than other types of projects such as distributed services and other common types. Everything is quite deterministic in the sense that most can be simulated with a couple of git repositories locally. Then you get reproducible results, fairly fast to run.

We don't have as many unit tests as a large chunk of our code is calling git commands so it wouldn't be too interesting to test we called it with some particular arguments.

Most important are integration tests that flow code locally between git folders (example) and E2E tests which test...

The VMR resulted in the bizarre release https://github.com/dotnet/command-line-api/releases/tag/v2.0.2 whose release notes contain only a “Full Changelog” link, which points to a page that says “v2.0.1 and v2.0.2 are identical.”

Hi,

I am not sure this is a direct result of us having the VMR but I will ask around why there was such a release.

This makes it more difficult to see what changed in a release of a NuGet package, in order to understand

* whether the release includes any fixes that make the upgrade more urgent, and

* whether I need to modify applications that use the package.

I can compare the actual sources by cloning the VMR and using git diff on that, but it's more cumbersome because:

* A clone of the VMR takes far more disk space than the product repository. Even "git init --bare" followed by "git fetch --depth=1 https://github.com/dotnet/dotnet tag v10.0.1 tag v10.0.2" and "git repack -a -d" takes 474...

I see. So by discrepancy you mean the fact the repo has a tag on a commit that does not represent the shipped package?

In that sense you're right. We have discussed whether we will stop tagging the product repositories after a release as we're really releasing only a commit from the VMR.

We concluded that it will still be useful to tag the closest commits in the product repositories nearest to what we're releasing - in this case the last commit that has been flowed into the VMR - as it's still very useful to see when later comparing...

The System.CommandLine.* NuGet packages were published from the VMR dotnet/dotnet, not from the dotnet/command-line-api repository. In the VMR, between the tags v10.0.1..v10.0.2, https://github.com/dotnet/dotnet/commit/18f6e60aa4755c2be56b2d45165a135d64d4f710 (Nov 20, 2025) changed the version number in src/command-line-api/eng/Versions.props. This change later flowed to dotnet/command-line-api repository as part of https://github.com/dotnet/command-line-api/pull/2741 (Dec 4, 2025) but the tag v2.0.2 there does not include it.

If there were no VMR and the NuGet packages were published straight from dotnet/command-line-api, then this kind of discrepancy could not happen.