With the arrival of commodity depth-capable cameras, specifically, the Microsoft Kinect, as well as high-performance machine learning algorithms, entirely new capabilities are made possible. Working with academic experts and others, we are attempting to track the movements, body language, and vocalizations of dogs.

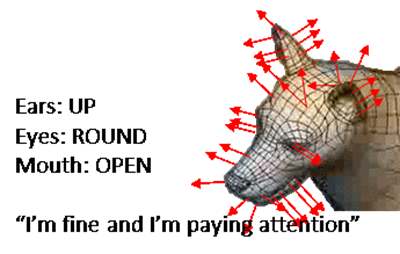

The overall goal of this project is to decode the communications of dogs. This TED Case Study covers one aspect of this project, specifically, progress in visually tracking dogs. Future papers will cover feature detection and analysis (e.g., ear position, mouth expressions, tail decoding); audio analysis (barks); and development and deployment an application. Eventually, the objective is to analyze all of these factors in toto and be able to infer (for example) if ears are up, mouth is open, tail is up, dog is silent: I’m alert, I’m paying attention, I’m not feeling aggressive or threatened.

Figure 1. Conceptual Goal of Project

Overview of the Solution

Project “Dolittle” initially leveraged the open source computer vision library OpenCV (http://www.opencv.org). OpenCV supports image detection, object recognition, various machine learning algorithms, classifiers, and video analysis, among other capabilities. Initial work focused on training OpenCV’s Haar cascades to recognize one dog, in this case, a Smooth-Haired Collie named “Mici”.

Figure 2. Mici

OpenCV uses a relatively typical training methodology. It receives a large number of annotated pictures as input. Here the developer took roughly 400 pictures of Mici and hand-annotated them; the training process required approximately a week of processing time. This approach was deemed inappropriate, partly because of the training time and because such training would be required on a per dog basis! While it is likely that the training time could have been accelerated by the use of Azure scale, we believed this approach would ultimately not be flexible enough to support the infinite variation in dog shape and dog movement.

Nevertheless, object detection – especially moving objects such as animals – poses a formidable problem. The Kinect receives (through its IR camera) a depth stream in addition to the 30fps HD RGB color data.1 However, these constitute simply a point cloud that requires sophisticated analysis in order recognize a shape in real time. The current Kinect retail product presently leverages a massive amount of machine learning to perform human skeletal tracking.

Various other approaches were considered including Berkeley’s image processing machine learning library Caffe (http://caffe.berkeleyvision.org/), internal Kinect code, and others.

Eventually, the team collaborated with a group in Microsoft Research, which had built software for very high-resolution, real-time hand tracking. Unlike other approaches, MSR used both machine learning and model fitting in real time to identify and track hands with extremely high fidelity. Supplementing machine learning with the ability to match a 3D mesh against the Kinect video stream enabled considerably more accuracy, as shown in the video located here. See as well the hand tracking paper presented at SIGCHI 2015 here.

Figure 3. Hand Tracking Video

However, the problem of dog tracking (and by extension similar large objects that move) has some differences with hand tracking:

- For our purposes, extreme real-time tracking (that is, at 30 frames per second) is not really required as the goal is to detect the dog’s expressions, which do not change as fast

- However, background removal is a significant issue that the hand tracking demo did not have to address

- There is substantial variation in dog shapes (because of breeds): small, large, with large snouts, small, with tails, without tails, colors, and so on.

A multi-stage pipeline is used to recognize an object. The process matches predefined depth-aware “poses” (approximately 100,000 of them)2 to what the Kinect sees. To do this matching, a jungle ML algorithm3 is used to detect a set of candidate poses and then a particle swarm optimization algorithm performs “model fitting”. In model fitting, the observed image is matched against prebuilt poses and the best choice is selected.

Figure 4. Model Fitting Visualization

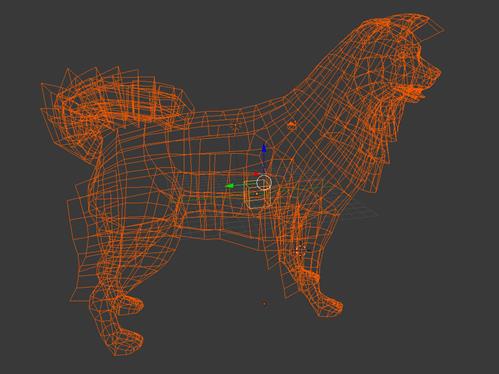

To create the poses, a “rigged” (articulated) Blender 3D model, such as the hand model below, is used:

Figure 5. Rigged Hand Model in Blender

(“Rigged” meaning that the 3D mesh includes “bones” and the model can be articulated.) Poses of the model rotated in 3d space can be used to test the recognition. These models are then rotated and articulated to get the thousands of poses that will be used to “model fit” against the observed Kinect data.

An example of a dog model (a border collie) in Blender is shown below:

Figure 6. Border Collie in Blender

These models can be used as the basis for building poses which the ML algorithms will use to track the dog in question.

Initially, the goal of this project was modest: to track one or two specific dogs (Ilkka’s dog Mici and Barry’s dog Joe). Later the project will be able to recognize and tune for different sizes and breeds, using machine learning and likely leveraging training data sets such as the Stanford Dogs Dataset (an annotated library of some 22,000 dog images – http://vision.stanford.edu/aditya86/ImageNetDogs/ ) and potentially using such techniques as model deformation to match different breeds.

We have been able to track Ilkka’s dog Mici in real time, with some limitations (see the TED Case Study entitled “Background and Floor Removal from Depth Camera Data” for a discussion of one of the thorniest issues). The next step was to improve the tracking and then move on to identify features on the dog – ear position, tail wag rate, and so forth – in order to infer the dog’s state of mind. In addition, work is also under way to use machine learning algorithms to decipher dog vocalizations; these topics and others will be discussed in future case studies.

Code Artifacts

OpenCV is at http://www.opencv.org .

The Kinect SDK is at http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/kinectforwindows/

Opportunities for Reuse

We believe this project has numerous possibilities for reuse. The most significant accomplishment of the project to date is to demonstrate that real time, very high fidelity reconstruction (far more significant than 3D cameras out of the box) is possible. Further, since the model fitting uses 3D models that can be tagged, feature extraction (e.g., ear position) is made possible, and this capability leads to a number of important scenarios.

It should be possible, using the code base, to extend the recognition to other animals such as cats (actually, a much easier problem given that physical variation among cat breeds is substantially less than for dogs) and possibly horses.

The resolution of the tracking enables scenarios previously difficult or impossible for Kinect. For example, 24-hour scanning of premature human babies is, with work, feasible (as the out of the box Kinect has certain minimum size limitations); in addition, similar scanning for normal babies (for terrified new parents) could also be done and there are a number of similar scenarios. Finally, such technology could be used for the benefit of Alzheimer’s and other physically challenged individuals.

For more specifics on the Kinect, see here; for the Kinect SDK, see here.

Initial set. One of the goals of the project is to see if we can match with substantially fewer prebuilt poses.

For more on decision jungles, see here. To quote: “Unlike conventional decision trees that only allow one path to every node, a DAG [Directed Acyclic Graph] in a decision jungle allows multiple paths from the root to each leaf.”