For the last several Visual Studio release cycles, the Windows Forms (WinForms) Team has been working hard to bring the WinForms designer for .NET applications to parity with the .NET Framework designer. As you may be aware, a new WinForms designer was needed to support .NET Core 3.1 applications, and later .NET 5+ applications. The work required a near-complete rearchitecting of the designer, as we responded to the differences between .NET and the .NET Framework based WinForms designer everyone knows and loves. The goal of this blog post is to give you some insight into the new architecture and what sorts of changes we have made. And of course, how those changes may impact you as you create custom controls and .NET WinForms applications.

After reading this blog post you will be familiar with the underlying problems the new WinForms designer is meant to solve and have a high-level understanding of the primary components in this new approach. Enjoy this look into the designer architecture and stay tuned for future blogs!

A bit of history

WinForms was introduced with the first version of .NET and Visual Studio in 2001. WinForms itself can be thought of as a wrapper around the complex Win32 API. It was built so that enterprise developers didn’t need to be ace C++ developers to create data driven line-of-business applications. WinForms was immediately a hit because of its WYSIWYG designer where even novice developers could throw together an app in minutes for their business needs.

Until we added a support for .NET Core applications there was only a single process, devenv.exe, that both the Visual Studio environment and the application being designed ran within. But .NET Framework and .NET Core can’t both run together within devenv.exe, and as a result we had to take the designer out of process, thus we called the new designer – WinForms Out of Process Designer (or OOP designer for short).

Where are we today?

While we aimed at complete parity between the OOP designer and the .NET Framework designer for the release of Visual Studio 2022, there are still a few issues on our backlog. That said, the OOP designer in its current iteration already has most of the significant improvements at all important levels:

- Performance: Starting with Visual Studio 2019 v16.10, the performance of the OOP designer has been improved considerably. We’ve worked on reducing project load times and improved the experience of interacting with controls on the design surface, like selecting and moving controls.

- Databinding Support: WinForms in Visual Studio 2022 brings a streamlined approach for managing Data Sources in the OOP designer with the primary focus on Object Data Sources. This new approach is unique to the OOP designer and .NET based applications.

- WinForms Designer Extensibility SDK: Due to the conceptional differences between the OOP designer and the .NET Framework designer, providers for 3rd party controls for .NET will need to use a dedicated WinForms Designer SDK to develop custom Control Designers which run in the context of the OOP designer. We have published a pre-release version of the SDK last month as a NuGet package, and you can download it here. We will be updating this package to make it provide IntelliSense in the first quarter of 2022. There will also be a dedicated blog post about the SDK in the coming weeks.

A look under the hood of the WinForms designer

Designing Forms and UserControls with the WinForms designer holds a couple of surprises for people who look under the hood of the designer for the first time:

- The designer doesn’t “save” (serialize) the layout in some sort of XML or JSON. It serializes the Forms/UserControl definition directly to code – in the new OOP designer that is either C# or Visual Basic .NET. When the user places a Button on a Form, the code for creating this Button and assigning its properties is generated into a method of the Form called `InitializeComponent`. When the Form is opened in the designer, the `InitializeComponent` method is parsed and a shadow .NET assembly is being created on the fly from that code. This assembly contains an executable version of `InitializeComponent` which is loaded in the context of the designer. `InitializeComponent` method is then executed, and the designer is now able to display the resulting Form with all its control definitions and assigned properties. We call this kind of serialization Code Document Object Model serialization, or CodeDOM serialization for short. This is the reason, you shouldn’t edit `InitializeComponent` directly: the next time you visually edit something on the Form and save it, the method gets overwritten, and your edits will be lost.

- All WinForms controls have two code layers to them. First there is the code

for a control that runs during runtime, and then there is a control

designer, which controls the behavior at design-time. The control designer

functionality for each control is not implemented in the designer

itself. Rather, a dedicated control designer interacts with Visual Studio

services and features.Let’s look at `SplitContainer` as an example:

The design-time behavior of the SplitContainer is implemented in an associated designer, in this case the `SplitContainerDesigner`. This class provides the key functionality for the design-time experience of the `SplitContainer` control:

- The way the outer Panel and the inner Panels get selected on mouse click.

- The ability of the splitter bar to be moved to adjust the sizes of the inner panels.

- To provide the Designer Action Glyph, which allows a developer using the control to manage the Designer Actions through the respective short cut menu.

When we decided to support apps built on .NET Core 3.1 and .NET 5+ in the original designer we faced a major challenge. Visual Studio is built on .NET Framework but needs to round-trip the designer code by serializing and deserializing this code for projects which target a different runtime. While, with some limitations, you can run .NET Framework based types in a .NET Core/.NET 5+ applications, the reverse is not true. This problem is known as “type resolution problem”. A great example of this can be seen in the TextBox control: in .NET Core 3.1 we added a new property called `PlaceholderText`. In .NET Framework that property does not exist on `TextBox`. So, if the .NET Framework based CodeDom Serializer (running in Visual Studio) encountered the `PlaceholderText` property it would fail.

In addition, a Form with all its controls and components renders itself in the designer at design time. Therefore, the code that instantiates the form and shows it in the Designer window must also be executed in .NET and not in .NET Framework, so that newer properties available only in .NET also reflect the actual appearance and behavior of the controls, components, and ultimately the entire Form or UserControl.

Because we plan to continue innovating and adding new features in the future, the problem only grows over time. So we had to design a mechanism that supported such cross-framework interactions between the WinForms designer and Visual Studio.

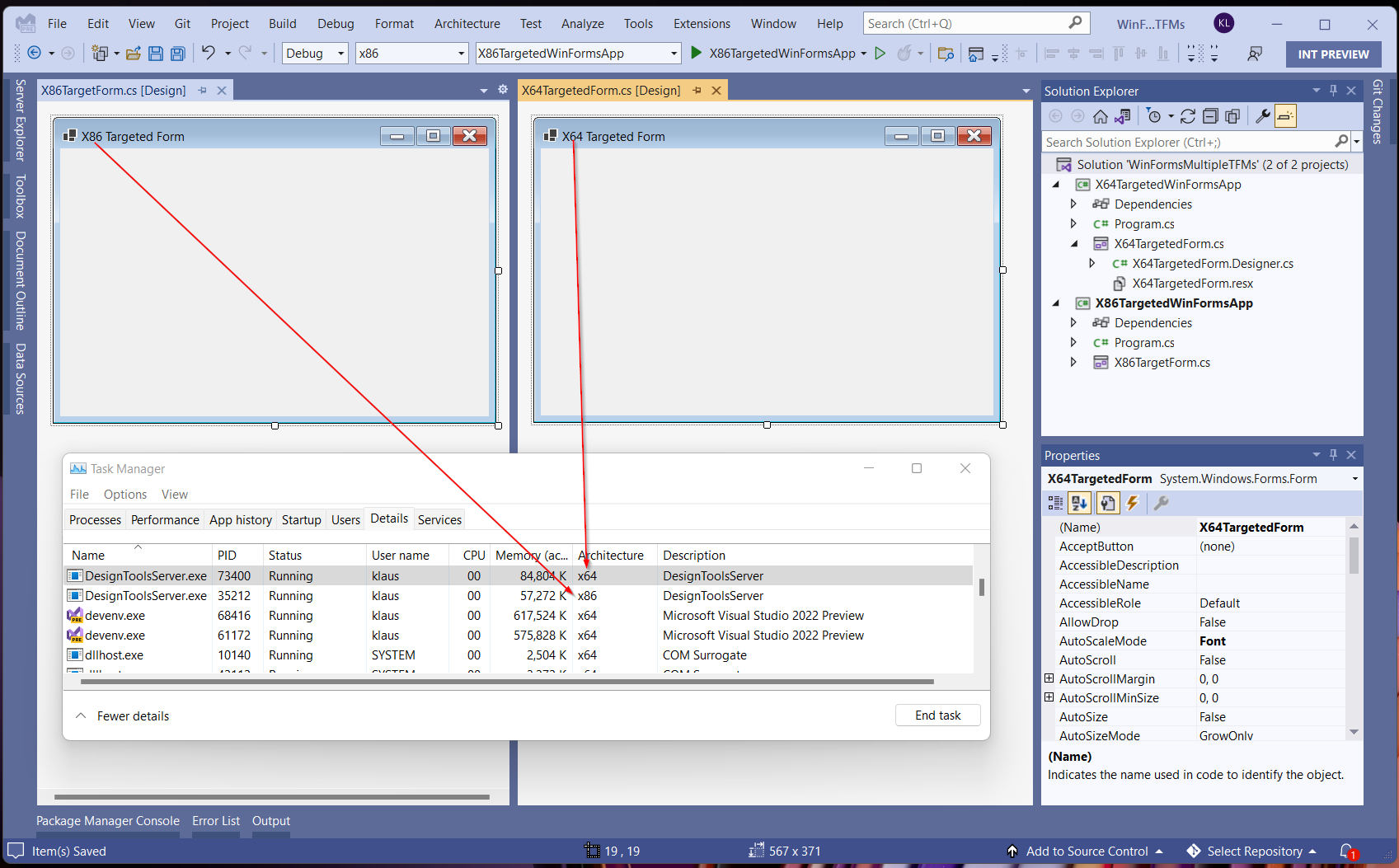

Enter the DesignToolsServer

Developers need to see their Forms in the designer looking precisely the way it will at runtime (WYSIWYG). Whether it is `PlaceholderText` property from the earlier example, or the layout of a form with the desired default font – the CodeDom serializer must run in the context of the version of .NET the project is targeting. And we naturally can’t do that, if the CodeDom serialization is running in the same process as Visual Studio. To solve this, we run the designer out-of-process (hence the moniker Out of Process Designer) in a new .NET (Core) process called DesignToolsServer. The DesignToolsServer process runs the same version of .NET and the same bitness (x86 or x64) as your application.

Now, when you double-click on a Form or a UserControl in Solution Explorer, Visual Studio’s designer loader service determines the targeted .NET version and launches a DesignToolsServer process. Then the designer loader passes the code from the `InitializeComponent` method to the DesignToolsServer process where it can now execute under the desired .NET runtime and is now able to deal with every type and property this runtime provides.

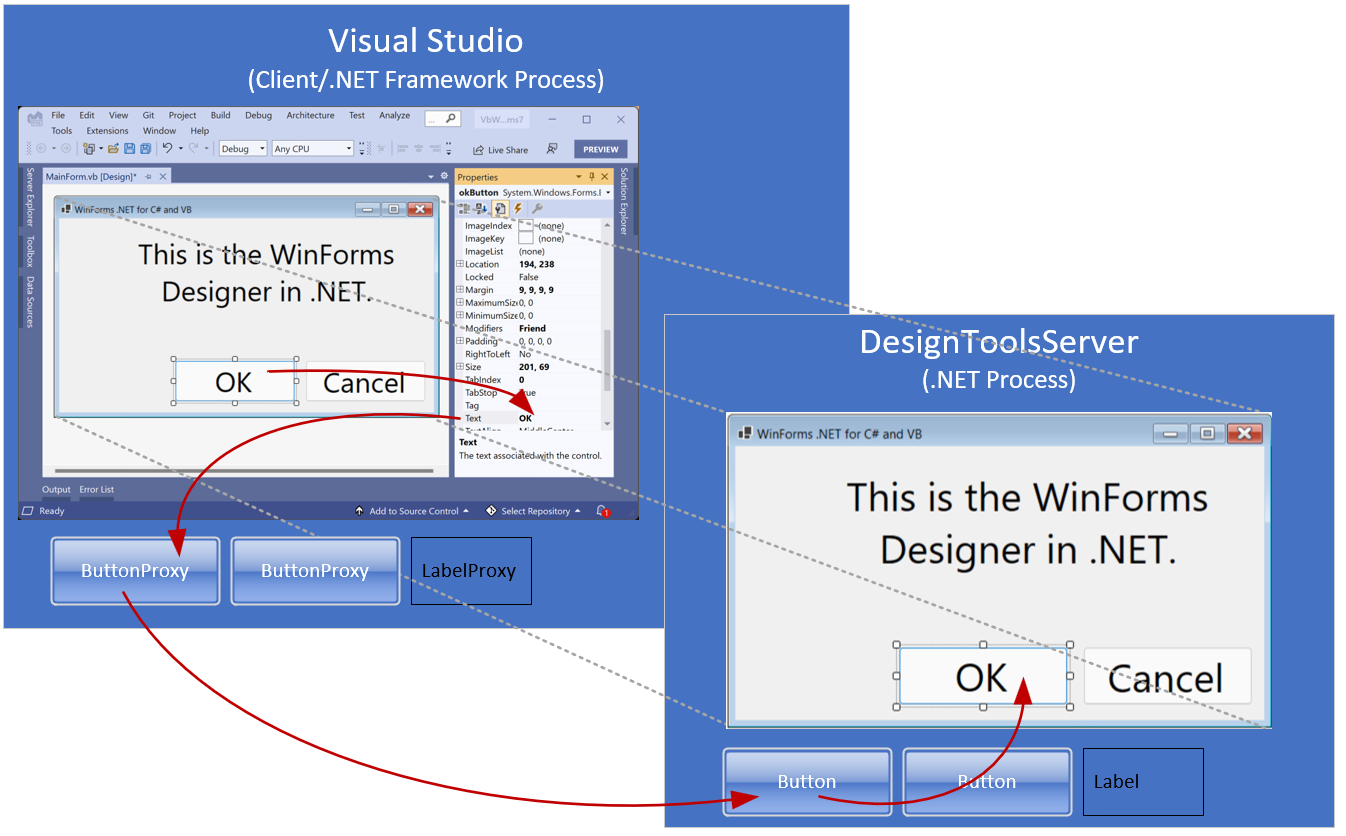

While going out of process solves the type-resolution-problem , it introduces a few other challenges around the user interaction inside Visual Studio. For example, the Property Browser, which is part of Visual Studio (and therefore also .NET Framework based). It is supposed to show the .NET Types, but it can’t do this for the same reasons the CodeDom serializer cannot (de)serialize .NET types.

Custom Property Descriptors and Control Proxies

To facilitate interaction with Visual Studio, the DesignToolsServer introduces proxy classes for the components and controls on a form which are created in the Visual Studio process along with the real components and controls on the form in the DesignToolsServer.exe process. For each one on the form, an object proxy is created. And while the real controls live in the DesignToolsServer process, the object proxy instances live in the client – the Visual Studio process. If you now select an actual .NET WinForms control on the form, from Visual Studio’s perspective an object proxy is what gets selected. And that object proxy doesn’t have the same properties of its counterpart control on the server side. It rather maps the control’s properties 1:1 with custom proxy property descriptors through which Visual Studio can talk to the server process.

So, clicking now on a button control on the form, leads to the following (somewhat simplified) chain of events to get the properties to show in the Property Browser:

- The mouse click happens on special window in the Visual Studio process, called the Input Shield. It acts like a sneeze guard, if you will, and is purely to intercept the mouse messages which it sends to the DesignToolsServer process.

- The DesignToolsServer receives the mouse click and passes it to the Behavior Service. The Behavior Service finds the control and passes it to the Selection Service that takes the necessary steps to select that control.

- In that process, the Behavior Service has also located the correlating Control Designer, and initiates the necessary steps to let that Control Designer render whatever adorners and glyphs it needs to render for that control. Think of the Designer Action Glyphs or the special selection markers from the earlier SplitPanel example.

- The Selection Service reports the control selection back to Visual Studio’s Selection Service.

- Visual Studio now knows, what object proxy maps to the selected control in the DesignToolsServer. The Visual Studio’s selection service selects that object proxy. This again triggers an update for the values of the selected control (object proxy) in the Property Browser.

- The Property Browser in turn now queries the Property Descriptors of the selected object proxy which are mapped to the proxy descriptors of the actual control in the DesignToolsServer’s process. So, for each property the Property Browser needs to update, the Property Browser calls GetValue on the respective proxy Property Descriptor, which leads to a cross-process call to the server to retrieve the actual value of that control’s property, which is eventually displayed in the Property Browser.

Compatibility of Custom Controls with the DesignToolsServer

With the knowledge of these new concepts, it is obvious that adjustments to existing custom control designers targeting .NET will be required. The extent to which the adjustments are necessary depends purely on how extensively the custom control utilize the typical custom Control Designer functionality.

Here’s a simple a simplified guide on how to decide whether a control would likely require adjustments for the OOP designer for typical Designer functionality:

- Whenever a control brings a special UI functionality (like custom adorners, snap lines, glyphs, mouse interactions, etc.), the control will need to be adjusted for .NET and at least recompiled against the new WinForms Designer SDK. The reason for this is that the OOP Designer re-implements a lot of the original functionality, and that functionality is organized in different namespaces. Without recompiling, the new OOP designer wouldn’t know how to deal with the control designer and would not recognize the control designer types as such.

- If the control brings its own Type Editor, then the required adjustments are more considerable. This is the same process the team underwent with the library of the standard controls: While the modal dialogs of a control’s designer can only work in the context of the Visual Studio process, the rest of the control’s designer runs in the context of the DesignToolServer’s process. That means a control with a custom type editor, which is shown in a modal dialog, always needs a Client/Server Control Designer combination. It needs to communicate between the modal UI in the Visual Studio process and the actual instance of the control in the DesignToolsServer process.

- Since the control and most of its designers now live in the DesignToolsServer (instead of Visual Studio) process, reacting to a developer’s UI interaction by handling those in WndProc code won’t work anymore. As already mentioned, we will publishing a blog post that will cover the authoring of custom controls for .NET and dive into the .NET Windows Forms SDK in more details.

If a Control’s property, however, does only implement a custom Converter, then no change is needed, unless the converter needs a custom painting in the property grid. Properties, however, which are using custom Enums or provide a list of standard settings through the custom Converter at design time, are running just fine.

Features yet to come and phased out Features

While we reached almost parity with the .NET Framework Designer, there are still a few areas where the OOP Designer needs work:

- The Tab Order interaction has been implemented and is currently tested. This feature will be available in Visual Studio 17.1 Preview 3. Apart from the Tab Order functionality you already found in the .NET Framework Designer, we have planned to extend the Tab Order Interaction, which will make it easier to reorder especially in large forms or parts of a large form.

- The Component Designer has not been finalized yet, and we’re actively working on that. The usage of Components, however, is fully supported, and the Component Tray has parity with the .NET Framework Designer. Note though, that not all components which were available by default in the ToolBox in .NET Framework are supported in the OOP Designer. We have decided not to support those components in the OOP Designer, which are only available through .NET Platform Extensions (see Windows Compatibility Pack). You can, of course, use those components directly in code in .NET, should you still need them.

- The Typed DataSet Designer is not part of the OOP Designer. The same is true for type editors which lead directly to the SQL Query Editor in .NET Framework (like the DataSet component editor). Typed DataSets need the so-called Data Source Provider Service, which does not belong to WinForms. While we have modernized the support for Object Data Sources and encourage Developers to use this along with more modern ORMs like EFCore, the OOP Designer can handle typed DataSets on existing forms, which have been ported from .NET Framework projects, in a limited scope.

Summary and key takeaways

So, while most of the basic Designer functionality is in parity with the .NET Framework Designer, there are key differences:

- We have taken the .NET WinForms Designer out of proc. While Visual Studio 2022 is 64-Bit .NET Framework only, the new Designer’s server process runs in the respective bitness of the project and as a .NET process. That, however, comes with a couple of breaking changes, mostly around the authoring of Control Designers.

- Databinding is focused around Object Data Sources. While legacy support for maintaining Typed DataSet-based data layers is currently supported in a limited way, for .NET we recommend using modern ORMs like EntityFramework or even better: EFCore. Use the DesignBindingPicker and the new Databinding Dialog to set up Object Data Sources.

- Control library authors, who need more Design Time Support for their controls than custom type editors, need the WinForms Designer Extensibility SDK. Framework control designers no longer work without adjusting them for the new OOP architecture of the .NET WinForms Designer.

Let us know what topics you would like hear from us around the WinForms Designer- the new Object Data Source functionality in the OOP Designer and the WinForms Designer SDK are the topics already in the making and on top of our list.

Please also note that the WinForms .NET runtime is open source, and you can contribute! If you have ideas, encountered bugs, or even want to take on PRs around the WinForms runtime, have a look at the WinForms Github repo. If you have suggestions around the WinForms Designer, feel free to file new issues there as well.

Happy coding!

Great article and VS2022 is looking very good as well. I’ve been using it for a while now.

We have an ActiveX control written in C++ which is used by a WinForms FWv4.8 application.

We would like to port or rebuild this WinForms application to .NET6, but the Forms Designer doesn’t work with our ActiveX control.

I found a post saying that is by design and we can vote for it to get this changed.

So please vote for it at https://developercommunity.visualstudio.com/t/support-for-activex-controls-in-windows-forms-desi/1435698

Another day, another designer.

Don't get me wrong I much prefer the Winforms environment over, say WPF or UWP ( RIP ), but do we really need yet another way of placing UI elements on a display surface?

Back in the last century, Winforms were king. Then we went all webby, Visual Studio 6 allowed us to drop HTML controls on a page, then VS.Net took that a stage further with aspx (I also pine for Webforms by the way). Then Xamarin, ete etc.

In the early days of the interweb we all loved to hate IE6 etc. Now, Edge uses the Chromium...

Unless I’m misreading this, even if we were to use VS 2022 to target .NET Framework 4.8, we would still be using the new OOP designer; is that correct?

No, .NET Framework will always use old designer.

Well…

OK, thank you.

Hi, Is there any plan to have .NET Core 5+ WinForms on Linux?

No. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Klaus, there is one more problem with displaying forms from the OOP DesignToolsServer. This concerns both WinForms Forms and MessageBoxes. They are shown below the main VS IDE instance. It looks like a real deadlock - VS IDE becomes unresponsible when you click it, and the OS suggests to close devenv.exe. You must observe the taskbar and find the button for the opened dialog, then switch to it and close. But this taskbar button is hardly noticeable, especially in Windows 11.

BTW, setting Form.TopMost to True for the dialog also does not help. The form still appears under the main VS...

This is the reason that you cannot show UI from the DesignToolsServer. (See one of my previous responses).

A Control Designer which must show a (modal) UI (Editor) should only be shown in the context of Visual Studio (the client).

So. Such a Control Designer will then always have 2 parts: One for the Client (VS, .NET Framework), one for the Server (DesignToolsServer, .NET).

They both must be delivered via NuGet and get executed in their respective contexts.

And again, having the Designer OOP is really an architectural necessity. Framework being the host and .NET being the target is one challenge,...

I think that we really need some sort of discussion here.

May be open a new one?

This design of out of process designer seems quite complicated. Wouldn’t it have been simpler if Visual Studio was ported to .NET? If that’s not the case, then is Visual Studio going to be stuck in .NET Framework forever? I suppose not. Would be great if you can provide some clarity on the Visual Studio roadmap. Thanks.

It has more to do with the fact that they cannot unload and reload assemblies in .net 5/6. This is a common need, both in the windows forms designer, and pretty much all the other Visual Studio tools such as code analysis. Even if VS was completely ported over, the problem would remain, and I don’t see any focus on that area.

Our root designer is not a control designer. We use the code dom serialization, and the property grid, and various services, but our components are IComponent derived classes, not Control derived. We have a root designer that is a graphical designer, generating an object graph that is serialized. Are root designers now supported?

Not at the moment. But that is likely to change, since we face the same challenge with the Component Designer.

Hi Klaus,

Thanks for this very helpful insights.

Do you have any insights on what is happening to licensed controls? In previous versions (.NET Framework), the designer created a licenses.licx and the LC.EXE compiled the licenses into the assembly resources. This concept is still possible, but them implies the BinaryFormatter problem.

Do you know, if there is going to be a new LC.EXE or another way to license controls in the .NET 5/6 world?

Thanks so much for your great work!

For all of the convenience, there were enough limitations to the LC.EXE model that we chose not to move that forward in the .NET 5/6 world. There are several approaches that customers can take including creating your own licensing model and code that into your controls or apps. Alternatively, you could use one of the 3rd party solutions that are available on the market now.

In addition: The License test for controls or components had room for improvement. It would not have reliably succeeded, for example, had the component (or the control) been instantiated at Design time by another Control/Component or its Parent and later sited.

Also, this license test was regularly abused to check if a component was in "some kind of Design mode". I had this discussion before, and I know there are different opinions about that. Still my strongly 2 cents are what also the official and original definition of DesignMode is: A Control or Component is in DesignMode, if it's sited and...

All these "challenges" just show how clumsy WinForms architecture is. Yes, from the point "let's roll WinForms ASAP" you have excuse. But WinForms exist 20 years - MS had enough time to think twice about "how to make WinForms really professional".

Say, nobody forces you to INSTANTIATE controls. All you need is LOOK of controls. (said enough) Also I doubt in necessarity of "full design time interaction". It's DESIGN, not RUNTIME! Even placeholder "there will be button" is enough (for the start). Conception of Delphi "make all apps with mouse only" shown that it's myth. XAML proven that writing declarative...

Klaus, one more thing regarding adding .NET-6-designer-compatible controls to the VS Toolbox. As I wrote in my previous comment, if I recompile the design-time functionality of our visual control with the Microsoft.WinForms.Designer.SDK Nuget package and pack the recompiled DLL into our own Nuget package, the control appears in the VS Toolbox when I add our Nuget package to a .NET 6 WinForms project. However, I can't add the control to the Toolbox directly using the Choose Items... command from the Toolbox context menu. I see the following message box when I select the DLLs in the Choose Toolbox Items dialog:

<path...

The official recommendation is that you use the Nuget approach for distributing your controls.

To Frank and Merrie: we are not happy with this decision, to put it mildly.

To Merrie and VS dev team: please, bring back the old way allowing VS IDE to find design-time DLLs. I think you just need to ‘turn on’ what has worked for decades – for example, the AssemblyFoldersEx reg key. And re-enable the ability to add controls to the VS Toolbox as earlier.

Well, as mentioned in the blog (and I hope I got you correctly): The problem still is that a .NET assembly (which your designer most likely would be) cannot run in the context of Visual Studio.

So, I can only suggest: Wait for the OOP Designer Blog Post, which should be released in February (aiming first half, maybe even a bit earlier), which makes all the more transparent, why we need to refactor some of the Control Designer scenarios, why the need to be recompiled against the SDK and how to do it.

That doesn’t sound especially practical. Is that being done often for commercial components?

There is a serious problem with this approach for commercial software like our WinForms grid control. As a rule, the design-time functionality for a commercial control is implemented in a separate DLL not intended for redistribution with end-user apps. If the developer is writing a WinForms app for .NET Core 3.x/5/6, we must include the design-time DLL into the Nuget package attached to the project. But this means that the design-time DLL will be copied to the bin folder with the compiled app and, as it often happens, redistributed with the app.

Currently we avoid this for .NET Framework projects by...

Not only should the design time dll not be redistributed (for licensing reasons), it doesn’t need to be redistributed. It would be wasteful.