.NET 5 is the next version and future of .NET. We are continuing the journey of unifying the .NET platform, with a single framework that extends from cloud to desktop to mobile and beyond. Looking back, we took the best of .NET Framework and put that into .NET Core 3, including support for WPF and Windows Forms. As we continue the journey, we will move Xamarin and .NET web assembly to use the .NET 5 libraries, and extend the dotnet tools to target mobile and web assembly in the browser. At the same time, we’ll continue to improve .NET capabilities as a leading cloud and container runtime.

You can tune in to hear Scott Hanselman and I talk about .NET 5 and beyond in our “The Journey to One .NET” talk today.

We want to hear from you! Share your feedback about .NET 5 at https://aka.ms/dotnet5_feedback_blog. We greatly value your feedback and use it to help make decisions on the future of .NET.

Last year, we laid out our vision for one .NET and .NET 5. we said we would take .NET Core and Mono/Xamarin implementations and unify them into one base class library (BCL) and toolchain (SDK). In the wake of the global health pandemic, we’ve had to adapt to the changing needs of our customers and provide the support needed to assist with their smooth operations. Our efforts continue to be anchored in helping our customers address their most urgent needs. As a result, we expect these features to be available in preview by November 2020, but the unification will be truly completed with .NET 6, our Long-Term Support (LTS) release. Our vision hasn’t changed, but our timeline has.

We remain committed to one .NET platform and will deliver a quality .NET 5 release in November this year. You’ll continue to see a wave of innovation happening with multiple previews on the journey to one .NET.

Download Preview 4

You can download .NET 5.0 Preview 4, for Windows, macOS, and Linux:

ASP.NET Core, and EF Core are also being released today. PowerShell has a .NET 5-based release today and now releases on the .NET schedule.

You need Visual Studio 2019 16.6 or later versions to use .NET 5.0. To use .NET 5.0 with Visual Studio Code, install the latest version of the C# extension. .NET 5.0 isn’t yet supported with Visual Studio for Mac.

Release notes:

- .NET 5.0 release notes

- .NET 5.0 known issues

- .NET Core 3.1 -> .NET 5.0 API diff

- GitHub release

- GitHub tracking issue

.NET 5 Highlights

Let’s take a look at some of the release highlights that we expect to deliver with .NET 5, in November. Many of these changes are included, in part or in full, in Preview 4. The highlights will paint a clearer picture on the improvements you’ll get to take advantage of in your development process and in production when you adopt .NET 5.

- Includes C# 9 and F# 5.

- Performance — Improve performance throughout the product.

- Regular expressions

- Improve performance of

string.ToUpperInvariant,string.ToLowerInvariant,char.ToUpperInvariant,char.ToLowerInvariant, and other related patterns - Improve HTTP 1.1 performance

- Improve HTTP/2 performance

- Improve tiered compilation performance

- Improve stack prolog zeroing performance

- Improve performance of tailcalls used by F#

- Consistent performance: We have increased our focus on predictably consistent performance, reducing performance cliffs and outliers, with an emphasis on P95+ latency.

- Improve call counting mechanism used by tiered JIT compilation to smooth out performance during startup

- Dynamic expansion of internal generic dictionary that eliminate performance cliffs hit by generic code

- Pinned object heap to reduce heap fragmentation caused by pinning

- Reduce GC pause times in specific situations, like Array.Copy, Array.Sort or object unboxing

- Single file applications — a new single-file publish type that executes your app out of a single binary (for example, can be used on read-only media).

- Windows ARM64 — Enable .NET to run natively on Windows ARM64, supporting both development scenarios and deployment of client apps on customer machines.

- ARM64 — Improve ARM64 performance (Linux and Windows) in the JIT and BCL libraries.

- Containers — Reduce container image size and implement new container APIs to enable .NET to stay up-to-date with container runtime evolution.

- New Target Framework — We have adopted a new approach for .NET TFMs.

- JSON APIs — Enable easier migration from Newtonsoft.Json to System.Text.Json.

I’ll share some more detailed information about some of these improvements, and where we see them headed.

.NET 5.0 Target Framework

We are changing the approach we use for target frameworks with .NET 5.0. The following two project file examples demonstrate using .NET Core 3.1 and .NET 5.0 target frameworks, by specifying the respective Target Framework Moniker (TFM). You can see a new, more compact, TFM for .NET 5.0:

.NET Core 3.0:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp3.1</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

.NET 5.0:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>net5.0</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

We are making several important changes to .NET TFMs for .NET 5.0, to simplify using them, reduce concepts, and to make it easier to expose operating-system-specific APIs.

Here is a quick summary:

Targeting API versions will be simpler with .NET going forward. We won’t have two families of TFMs, like: netcoreapp3.1 and netstandard2.0. Instead, we’ll have just one, like: net5.0, and net6.0. That’s because there is just one .NET implementation going forward, so there is no longer a need for .NET Standard (which made libraries compatible across multiple .NET products). You’ll also be able to target operating system APIs, with a small extension to the TFM, like net5.0-windows and net6.0-android. We’ll also remove the different SDKs from new project files, like Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk.WindowsDesktop" since net5.0-windows, for example, will provide the same information. The biggest win is that by targeting net5.0, you get access to 100% of cross-platform APIs, not the subset that happened to be in .NET Standard. It will always be obvious which TFM to use (it’s either portable code or OS-specific), and you’ll never have to wait for APIs like Span<T> to be available.

Here are the details:

net5.0is the new Target Framework Moniker (TFM) for .NET 5.0.net5.0combines and replaces thenetcoreappandnetstandardTFMs.net5.0supports .NET Framework compatibility modenet5.0-windowswill be used to expose Windows-specific functionality, like Windows Forms and WPF.- .NET 6.0 will use the same approach, with

net6.0and will addnet6.0-iosandnet6.0-android. - The OS-specific TFMs can include OS version numbers, like

net6.0-ios14. - Portable frameworks, like ASP.NET Core and Xamarin.Forms, will be usable with

net5.0.

These changes are a result of thinking of .NET Core as the future of .NET. We’ve been removing the “Core” name from various aspects of the product, including APIs and container repos. We also saw an opportunity to further simplify .NET, by removing .NET Standard as a concept, for .NET 5.0+. .NET Standard has played a key role in establishing .NET Core, by creating a bridge with .NET Framework and Xamarin. The .NET Standard 2.0 version will remain relevant for many years, and we recommend you use it if you need to support .NET Framework. For apps and libraries that don’t need to run on .NET Framework, we recommend targeting the net5.0 TFM, which will give you access to the largest set of cross-platform APIs. For Xamarin, .NET Standard 2.0 and 2.1 remain relevant, however, once Xamarin is integrated into .NET as part of .NET 6.0, then it will switch to net6.0 TFMs, and developers will target .NET Standard 2.0 exclusively for .NET Framework compatibility.

You likely have more questions you want answered. We’ll be publishing a larger blog post on this topic before we release .NET 5.0. The following points answer some of the most obvious remaining questions:

netcoreapp5.0was used in earlier previews and is no longer supported, however still works.- Existing .NET Standard versions will work forever, and their continued use is supported.

- We don’t expect to create any new

netstandardversions. .NET Standard 2.1 will likely be the last version. - There are no plans for a

net5.0-linuxTFM since we don’t (yet) expose any Linux-specific APIs. Also, “Linux” is not a single uniform quantity, so it is unclear which APIs would be exposed in such a TFM. We could expose the POSIX standard, but then we’d call itnet5.0-posix, and it would work on operating systems other than just Linux. However, we don’t have plans for that either. - We do not plan to expose a TFM for web assembly, for similar reasons as described for Linux.

- You cannot update the

TargetFrameworkVersionin a .NET Framework project to 5.0 and expect it to become a .NET 5.0 project. It will not work. Instead, you need to port your application to .NET Core. For libraries, you can port to .NET Standard or .NET Core. We are no longer adding .NET Framework APIs to .NET Core, so there is no need to wait to port your application to .NET Core. - The new TFM plan is a foundational part of the workloads project. We will add minimal support for workloads in .NET 5.0 and then implement the complete vision in .NET 6.0.

C# 9

.NET 5 includes C# 9. C# 9 will have numerous features including Records, top-level statements, improved pattern matching, and much more. Here’s a sneak peek of some of the pattern matching improvements coming in the first preview:

You can play with this same code and experiment on your own at Sharplab.io.

To learn all about what’s coming with C# 9, check out Welcome to C# 9.

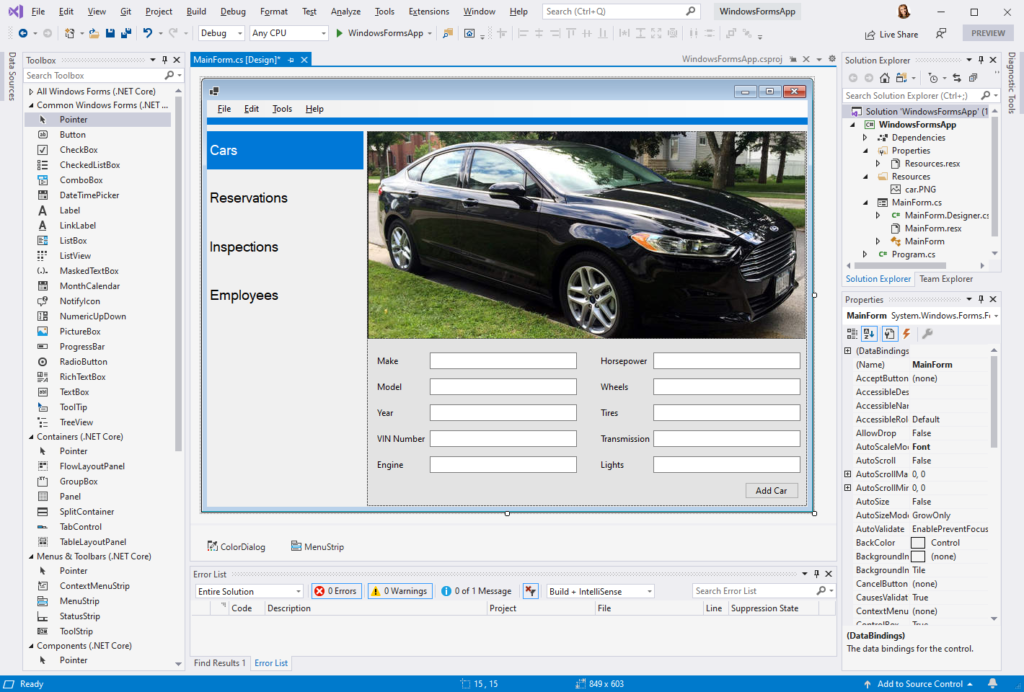

Windows Forms Designer for .NET Core Released

Today we’re happy to announce that the Windows Forms designer for .NET Core projects is now available as a preview in Visual Studio 2019 version 16.6! We also have a newer version of the designer available in Visual Studio 16.7 Preview 1!

To enable the designer in Visual Studio, go to Tools > Options > Environment > Preview Features and select the Use the preview Windows Forms designer for .NET Core apps option.

The new designer supports all Windows Forms controls, except DataGridView and ToolStripContainer (coming soon). It include all other designer functionality you would expect, including: drag-and-drop, selection, move and resize, cut/copy/paste/delete of controls, integration with the Properties Window, events generation and more. Data binding and support for third party controls are coming soon.

Windows ARM64

.NET apps can now run natively on Windows ARM64. This follows the support we added for Linux ARM64 in .NET Core 3.0. With .NET 5.0, you can develop web and UI apps on Windows ARM64 devices, and deliver your applications to users who own Surface Pro X and similar devices. You can already run .NET Core and .NET Framework apps on Windows ARM64, but via x86 emulation. It’s workable, but native ARM64 execution has much better performance.

You can download and use the .NET 5.0 SDK on ARM64 with today’s preview 4 release. Currently, only Console and ASP.NET Core apps are supported. See .NET 5.0 ARM64 tracking issue to track progress.

The master branch adds support for Windows Forms. This changes may make it into Preview 5, but Preview 6 for sure. You can download a master branch build from dotnet/installer.

At present, you need to download and expand .zip files for ARM64. We intend to add ARM64 MSIs for the final .NET 5 release.

We have been working closely with the PowerShell team to validate and enable PowerShell 7.1 on Windows ARM64. The team has had Windows ARM64 “experimental” builds for some time and intends to support PowerShell 7.1 on Windows ARM64, when they release. PowerShell 7.1 is built on .NET 5.0, and should be released around the same time.

The following image demonstrate the Conway’s Game of life VB and Windows Forms sample running on Windows ARM64.

ARM64 Performance

We’ve been investing significantly in improving ARM64 performance, for over a year. We’re committed to making ARM64 a high-performance platform with .NET. Platform portability and consistency have always been compelling characteristics of .NET. This includes offering great performance wherever you use .NET. With .NET Core 3.x, ARM64 has had functionality parity with x64 but was missing some key performance features and investments. We’re making the first big investments in ARM64 performance in .NET 5.0.

There are several categories of improvements we’re making:

- Tune JIT optimizations for ARM64 (example)

- Enable and take advantage of ARM64 hardware intrinsics (example).

- Adjust performance-critical algorithms in libraries for ARM64 (example).

See Improving ARM64 Performance in .NET 5.0 to track our progress.

Hardware intrinsics are a low-level performance feature we added in .NET Core 3.0. At the time, we added support for x64 instructions and chips. As part of .NET 5.0, we are extending the feature to support ARM64. Just creating the intrinsics doesn’t help performance. You need to use them in performance-critical code. We’ve taken advantage of ARM64 intrinsics extensively in .NET libraries in .NET 5.0. You can also do this in your own code, although you need to be be familiar with CPU instructions to do so.

I’ll explain how hardware intrinsics work with an analogy. For the most part, developers rely on types and APIs built into .NET, like String.Split or HttpClient. Those APIs often take advantage of native operating system APIs, via the P/Invoke feature. P/Invoke enables high-performance native interop, and is used extensively in the BCL for that purpose. You can use this same feature yourself to call native APIs. Hardware intrinsics are similar, except instead of calling operating system APIs, they enable you to directly use CPU instructions in your code. It’s roughly equivalent to a .NET version of C++ intrinsics. Hardware intrinsics are best thought of as a CPU hardware-acceleration feature. They provide very tangible benefits, are now a key part of the performance substrate of the .NET libraries, and responsible for many of the benefits you read about in our performance blog posts. In terms of comparison to C++, when .NET intrinsics are AOT-compiled into Ready-To-Run files, the intrinics have no runtime performance penalty.

Note: The Visual C++ compiler has an analogous intrinsics feature. You can directly compare C++ to .NET hardware intrinsics, as you can see if you search for _mm_i32gather_epi32 at System.Runtime.Intrinsics.X86.Avx2, x64 (amd64) intrinsics list, and Intel Intrinsics guide. You will see a lot of similarity.

We’re making our first big investments in ARM64 performance in 5.0, but will continue this effort in subsequent releases. We work directly with engineers from ARM Holdings to prioritize product improvements and to design algorithms that best take advantage of the ARMv8 ISA. Some of these improvements will accrue value to ARM32, however, we are not applying unique effort to ARM32.

Please share any performance information with us related to ARM64, either a notable improvement from 3.1 to 5.0, or performance with 5.0 that should be better.

P95+ Latency

We see an increasing number of large internet-facing sites and services being hosted on .NET. While there is a lot of legitimate focus on the requests per second (RPS) metric, we find that very few big site owners ask us about that or require millions of RPS. We hear a lot about latency, however, specifically about improving P95 or P99 latency. Often, the number of machines or cores that are provisioned for (and biggest cost driver of) a site are chosen based on achieving a specific P95 metric, as opposed to say P50. We think of latency as being the true “money metric”.

Our friends at Stack Overflow do a great job of sharing data on their service. One of their engineers, Nick Craver, recently shared improvements they saw to latency, as a result of moving to .NET Core:

The median page render time for questions dropped from about 21 ms (we were up a bit lately due to GC) to ~15ms.

The 95th percentile dropped from ~40ms to ~30ms (same measurement). 99th dropped from ~60ms to ~45ms.

Not too shabby, given we haven’t optimized anything at all yet. pic.twitter.com/MMHjI9wkuL

— Nick Craver (@Nick_Craver) March 31, 2020

While you can see that we’ve been making good progress on latency, we’re far from satisfied. In the (distant) past, we built features like server GC and background GC to improve latency, by taking advantage of course-grained CPU features like multiple-cores and threads, respectively. Those remain very important, however, we need to get a lot more creative to significantly improve latency moving forward, at least as it relates to the GC. We have started multiple projects along those lines.

Pinned objects have been a long-term challenge for GC performance, specifically because they accelerate (or cause) memory fragmentation. We’ve added a new GC heap for pinned objects. The pinned object heap is based on the assumption that there are very few pinned objects in a process but that their presence causes disproportionate performance challenges. It makes sense to move pinned objects — particularly those created by .NET libraries as an implementation detail — to a unique area, leaving the generational GC heaps with few or no pinned objects, and with substantially higher performance as a result.

More recently, we’ve been attacking long-standing “hard problems” in the GC. dotnet/runtime #2795 applies a new approach to GC statics scanning that avoids lock contention when it is determining liveness of GC heap objects. dotnet/coreclr #25986 uses a new algorithm for balancing GC work across cores during the mark phase of garbage collection, which should increase the throughput of garbage collection with large heaps, which in turn reduces latency.

Containers

We consider containers to be the most important cloud trend, and have been investing significantly in this modality. We are investing in containers in at least four different ways, at multiple levels of the .NET software stack.

The first is our investment in fundamentals. It’s a bit odd to claim credit for these investments, since they also benefit non-containerized workloads. What might not be obvious is that more and more of the feedback we receive that influences our fundamentals investment is coming from developers who deploy containerized apps. There is a bias to containers with these investments.

We are working on making .NET perform better in containers. We heard reports about poor performance related to a change in .NET Core 3.1 late last year (which was later reverted). We are now investigating the performance of using .NET in high-density and other configurations to help inform what we expect will be a relatively scoped set of changes that unlocks the next significant performance improvements in containers. It should be noted that .NET Core 3.0 was a very big release for .NET and containers, with the 3.1 issue being a small (and short-lived) blip.

We are always looking for opportunities to improve the images we publish. This includes reducing image size, but also extending the set of images we publish. We have decided to start publishing Windows Server Core images based on feedback we heard on GitHub and other sources. The following is an example Dockerfile that will be used when we start publishing these images. We’ve made other changes that reduce the size of Windows Server Core images, making them more attractive to use.

Last, we are working to make it easier to work with container orchestrators and similar environments. We are adding support for OpenTelemetry out of the box so that you can capture distributed traces and metrics from your application. We are also working on a new set of experimental tools in the dotnet/tye repo that are intended to improve microservices developer productivity, both for development and deploying to a Kubernetes environment.

Improving tiered compilation performance

We’ve been working on improving tiered compilation for multiple releases. We continue to see it as a critical performance feature, for both startup and steady-state performance. We’ve made two big improvements to tiered compilation this release.

The primary mechanism underlying tiered compilation is call counting. Once a method is called n times, the runtime asks the JIT to recompile the method at higher quality. From our earliest performance analyses, we knew that the call-counting mechanism was too slow (from a long-term standpoint), but didn’t see a straightforward way to resolve that. As part of .NET 5.0, we’ve improved the call counting mechanism used by tiered JIT compilation to smooth out performance during startup. In past releases, we’ve seen reports of unpredictable performance during the first 10-15s of process lifetime (mostly for web servers). That should now be resolved. Please test it and tell us what you see.

Another performance challenge we found was using tiered compilation for methods with loops. The fundamental problem is that you can have a cold method (only called once or a few times; < n) with a loop that iterates a million times. A great example of this pathological case is the Program.Main method of an application. As a result, we disabled tiered compilation for methods with loops by default. Instead, we enabled applications to opt into using tiered compilation for methods with loops. PowerShell is an application that chose to do this, after seeing high single-digit performance improvements in some scenarios.

To address methods with loops better, we implemented on-stack replacement (OSR). This is similar to a feature that the Java Virtual Machines has, of the same name. OSR enables code executed by a currently running method to be re-compiled in the middle of method execution, while those methods are active “on-stack”. This feature is currently experimental and opt-in (on x64).

To use OSR, multiple features must be enabled. The PowerShell project file is a good starting point. You will notice that tiered compilation and all quick-jit features are enabled. In addition, you need to set COMPlus_TC_OnStackReplacement=1 (its an environment variable).

Alternatively, you can set the following two environment variables, assuming all other settings have their default values:

COMPlus_TC_QuickJitForLoops=1COMPlus_TC_OnStackReplacement=1

We do not intend to enable OSR by default in .NET 5.0 and have not yet decided if we will support it in production. Please give us any and all feedback you have on the feature. We are actively testing it now and will share more insights on it later.

Single file applications

There are key scenarios where people want to use .NET where single-file distribution is a requirement, or at least preferred. We’ve been building up the key pieces that we need to enable this scenario over multiple releases, and will be including a new single file publish type in .NET 5.0. It’s a feature we expect to continue to refine over multiple releases.

There are two aspects that make this feature expensive to build:

- Accounting for different feature sets and constraints on Linux and Windows for loading executable content out of native resources.

- Ensuring that the debugger provides a multi-file-like experience for single-file applications.

For scoping purposes, we are supporting this feature on X64, for .NET 5.0, on Windows and Linux. It will work for ARM32/64 apps, however, we are not actively validating single files apps for the ARM architecture this release. Both runtime-dependent and self-contained publish types will be supported for single-file.

The experience between Windows and Linux is similar, but not the same. The differences are primarily relevant for self-contained single file applications, as described in the Single-file publish design doc:

- Single-file publish Linux:

dotnet publish -r linux-x64 /p:PublishSingleFile=true- Published files:

HelloWorld,HelloWorld.pdb

- Published files:

- Single-file publish Windows:

dotnet publish -r win-x64 /p:PublishSingleFile=true- Published files:

HelloWorld.exe,HelloWorld.pdb,coreclr.dll,clrjit.dll,clrcompression.dll,mscordaccore.dll

- Published files:

As you can see, on Windows, single-file self-contained applications require four additional files beyond the app. We were not able to include these runtime files into the single file app. We do not currently have a technical plan for hiding these extra files on Windows, even though we understand that it would be preferred.

Note: .pdb files are required only for debugging scenarios, and mscordaccore.dll is required to collect crash dumps, including by Windows Error Reporting (AKA “Watson”).

Improving migration from NewtonSoft.Json to System.Text.Json

We added System.Text.Json as part of the .NET Core 3.0 release. It provides significant performance improvements over Newtonsoft.Json, which has been the go-to Json library for .NET for many years. In some cases, it is hard to migrate to System.Text.Json, even with the migration guide we’ve provided. We’ve been working on targeted features that enable easier migration, without giving up on the performance value proposition of System.Text.Json.

We’ve added the following migration features with .NET 5.0:

- Add support for preserve references on JSON – Enables

ReferenceLoopHandling. - Add

JsonConstructorand support for deserializing with parameterized ctors — Adds support for immutable classes and structs to JsonSerializer. - Add JsonIgnoreCondition & per-property ignore logic – Adds support for null value handling.

- Add JsonIncludeAttribute & support for non-public accessors — Enables non-public getter usage, which is similar to the capability of the Newtonsoft.Json

JsonPropertyattribute.

At the same time, we’re also improving the usability of System.Text.Json:

- Add new System.Net.Http.Json project/namespace – Adds new extension methods for HttpClient that allow serialization from/to JSON.

- Add copy constructor to JsonSerializerOptions – Enables a library of framework to manage a

JsonSerializerOptionsinstance, with specific values it sets, while the type versions over time.

WinRT Interop

We are moving to a new model for supporting WinRT APIs as part of .NET 5.0. This includes calling APIs (in either direction; CLR <==> WinRT), marshaling of data between the two type systems, and unification of types that are intended to be treated the same across the boundary (i.e. “projected types”; IEnumerable<T> and IIterable<T> are examples).

We will rely on a new set of WinRT tools provided by the WinRT team in Windows that will generate C#-based WinRT interop assemblies. We are currently working closely with that team. The tools and the assemblies generated by them will be delivered for .NET 5.0.

There are several benefits to the new system:

- Can be developed and improved separate from the .NET runtime.

- Symmetrical with interop systems provided for other OSes, like iOS and Android.

- Can take advantage of many other .NET features (AOT, C# features, IL linking).

- Simplifies the .NET runtime codebase.

We will be removing the existing WinRT interop system from the .NET runtime (and any other associated components) as part of .NET 5.0. This means that apps using WinRT with .NET Core 3.x will need to be rebuilt and will not run on .NET 5.0 as-is.

Open source project improvements

We care a lot about open source, including enabling the .NET community to be productive on GitHub, and making .NET projects accessible to a large set of developers. We’ve been working on a variety of initiatives along those lines.

dotnet/source-build enables building the entire .NET project/product from source with a single command. Red Hat uses this project to build the version of .NET Core that they distribute, and we work closely with them on that. Fedora also uses source-build to enable .NET Core in their package repositories. We want to make it straightforward for any developer, organization or company to use source-build, and are investing significantly in the project. You can follow the .NET 5.0 source-build effort directly.

We started out the .NET Core project with too many GitHub repos. At its high, we had over 100 repos. That was too many to make sense to anyone, including the .NET Team. As part of the .NET 5.0 project, we decided to reduce the number of repos to a small and manageable collection. We announced our intention to consolidate .NET repos in August, 2019, and then provided a final update on the plan the following October. As part of that plan, we merged many repos together and almost all .NET repos are now in dotnet org, including dotnet/aspnetcore. We retained repo history as part of the effort, which had some funny side-effects. We continue to use the old repos for servicing the 2.1 and 3.1 product versions. MSBuild and NuGet client repos remain in other orgs.

We are also working on reducing build times for most repos. Quicker build times make everyone more productive, and enable you to see PR build results quicker. This is a longer-term effort, and a theme that will repeat in subsequent releases. You can track progress at .NET 5 Build Time Reduction Status.

We largely focus on improving the product, but are more recently turning our attention to improving the .NET open source project for contributors and other participants. We recently asked for feedback on improving the project and the experience participating in .NET repos. It is important to us that everyone feels like they have a voice (on project-related topics) on .NET project repos, that they are treated well, and that they can accomplish their goals. That doesn’t mean we accept every PR or suggestion filed as an issue. As it relates to our approach, we intend to use clear language, be neutral to kind in our engagement, and encourage contribution. Are we getting this right? What would you like to see us do differently or better? Please give us your feedback on our repo contribution experience survey.

We have been asked multiple times to clarify and liberalize .NET Core licenses. We’ve done that, each time moving source and binary assets to the MIT license. More recently, we’ve clarified the license we use for .NET Windows builds. For most users, these changes won’t matter much, but for others, they do, and we’ve done our best to satisfy their needs.

New improvements in Preview 4

The following improvements are new in Preview 4 and not otherwise covered in the earlier highlights section.

F# 5

Building on the F# 5 preview released earlier this year, the update to F# 5 includes support for consuming Default Interface Methods (DIMs) and some big performance improvements. Here’s a sneak peek at the DIMs support in F#:

You can read more with the F# 5 update for .NET 5 preview 4 post.

C# Source Generators update

This release also includes an update to the C# Source Generators preview. In addition to some bug fixes, it includes support for passing an analyzerconfig, which is essentially a list of key-value pairs, to a Source Generator. This lets your source generators work differently based on the input they recieve. For example, you may want to generate source code differently if a consuming project targets .NET Framework vs. .NET 5. Using an analyzerconfig allows you to pass information like a consuming project’s TFM to allow for exactly this scenario.

Support for ICU on Windows

We use the ICU library that provides Unicode and Globalization support for applications on Linux and macOS. We are now using this same library on Windows. This change makes the behavior of globalization APIs such as culture-specific string comparison consistent between Windows 10 and other operating systems.

Support for cgroup v2 (for containers)

.NET now has support for cgroup v2, which we expect will become an important container-related API in 2020 and beyond. Docker currently uses cgroup v1 (which is already supported by .NET). In comparison, cgroup v2 is simpler, more efficient, and more secure than cgroup v1. You can learn more about cgroup and Docker resource limits from our 2019 Docker update. Linux distros and containers runtimes are in the process of adding support for cgroup v2. .NET 5.0 will work correctly in cgroup v2 environments once they become more common. Credit to Omair Majid, who supports .NET at Red Hat.

Reducing the size of container images

We are always looking for opportunities to make .NET container images smaller and easier to use. We made a change in Preview 4 that dramatically reduces the size of the aggregate images you pull in multi-stage-build scenarios (which is a very common pattern). We re-based the SDK image on top of the ASP.NET image instead of buildpack-deps.

This change has the following win for multi-stage builds (example usage in Dockerfile):

Multi-stage build costs with Ubuntu 20.04 Focal:

| Pull Image | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

sdk:5.0-focal |

268 MB | 232 MB |

aspnet:5.0-focal |

64 MB | 10 KB (manifest only) |

Net download savings: 100 MB (-30%)

Multi-stage build costs with Debian 10 Buster:

| Pull Image | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

sdk:5.0 |

280 MB | 218 MB |

aspnet:5.0 |

84 MB | 4 KB (manifest only) |

Net download savings: 146 MB (-40%)

See dotnet/dotnet-docker #1814 for more detailed information.

This change helps multi-stage builds, where the sdk and the aspnet or runtime image you are targeting are the same version (we expect that this is the common case). With this change, the aspnet pull (for example), will be a no-op, because you will have pulled the aspnet layers via the initial sdk pull.

If you want a bit more context, keep reading. For 3.1 and prior, the SDK is based on the buildpack-deps image. When we started producing container images, we noticed other development platforms using buildpack-deps as the base of their tools/SDK images, so we followed the established pattern. We have specifically relied on the scm layer, which includes source-control tools and is based on the curl layer, which includes curl and similar network tools. That means that all those tools have been available to you in the SDK images. Unfortunately, this approach has come with a big tradeoff. Since Docker only allows for a single line of inheritance (each image can only have one parent), the sdk image needs to carry its own copy of ASP.NET, and Docker doesn’t see the actually identical ASP.NET bytes in the sdk image as the same as the ones in the aspnet image. That situation requires a lot of wasted bytes to be stored and transferred. On the other hand, people don’t want to give up using the tools provided by buildpack-deps.

As a compromise position, we re-based the sdk image on aspnet, added some of the tools back, while retaining 90+% of the size savings.

This explanation is descriptive of what we did for Ubuntu. The story with Debian is more complicated, and responsible for the larger size win. In short, the Debian variants of aspnet and runtime are based on the -slim Debian variant, while buildpack-deps is based on the non-slim Debian images. That means that for multi-stage builds with Debian, that you pull Debian twice! Even the distro layer hasn’t been shared until now.

We made similar changes for Alpine and Nano Server. There is no buildpack-deps image for either Alpine or Nano Server. However, the sdk images for Alpine and Nano Server were not previously built on top of the ASP.NET image. We fixed that. You will see significant size wins for Alpine and Nano Server as well with 5.0, for multi-stage builds.

We’ve known about these problems for a long time, but they had never been the next thing to go resolve. We decided that the 5.0 release was a good time to chase these size wins. Please tell us if there are any rough edges that we didn’t expect.

.NET 5.0 will switch to the dotnet container repo

As part of the move to “.NET” as the product name, we are now publishing .NET 5.0 Preview 4 and later images to the mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet family of repos, instead of mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/core. Please update your FROM statements and scripts accordingly. .NET Core 3.1 and 2.1 will continue to be published to mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/core. See dotnet/dotnet-docker #1939 for more information.

Closing

.NET 5.0 is shaping up to be another big foundational release, much like .NET Core 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0. It includes many new improvements that should make your applications and development process better and easier. Much of the team has been working on .NET 5 since before we released .NET Core 3.0. We’ve been looking forward to releasing all these improvements in a near-final form for many months, and will now watch for your feedback as you try them out.

As you can see from the product investments we’ve chosen, we’re focused on modern scenarios, and giving you straightforward and predictable solutions that power the portfolio of applications you need, to run your business or organization. It’s critical to us that you give us feedback to help us improve the features that you’ve read about here, but also with that you’d like to see next. As you may have seen earlier in the post, we’re already deep into planning the .NET 6.0 release, so its not too early to give us future-looking feedback.

Please Share your feedback about .NET at https://aka.ms/dotnet5_feedback_blog.

System.Text.Json on default is very bad idea. It has a lot of problems.

Just wanted to say thank you for all the hard work on .net 5. I hope you will take one more pass at Windows single file exe. Maybe you could extract those few dll out of the exe at runtime. That would be much better than having to bundle those files separately along with the exe.

Hello Scott,

when will be VB.Net supported?

Thank you!

Ismail

https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/windows-forms-designer-for-net-core-released/#comment-6268

https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/windows-forms-designer-for-net-core-released/#comment-6288

Please add support for Windows 2012 server! Otherwise we’re stuck with .NET Framework 4.8 until 2023 😥 And it’s a shame that Microsoft products don’t support Microsoft products…

I’m assuming your “journey” to “one .net” doesn’t include getting ASP.NET Web Forms working on .NET 5. So, you are not on a journey. In fact, you are making things diverge.

We are building one.net going forward. It will support all the modern modalities, like web, mobile, desktop, and IoT. It will not support specific implementations from the past, like ASP.NET Web Forms. Blazor is intended to support some of the same use cases as Web Forms.

I’m confused about WPF and WinForms, in preview 1 you said “A later preview will include WPF and Windows Forms”, what is the status of these platforms in .Net5?

Both WPF and Windows Forms are part of .NET 5 and part of Preview 4. They are not part of Preview 4 for ARM64, however.

What operation systems will be supported by .NET 5?

I’m especially curious about Windows 7 SP1 and Debian 9.

Thank you.

Supported OS versions for .NET 5 for mow include both Windows 7 SP1 and Debian 9.

Looks great! Kind of funny that Windows Single File Applications are going to be multi-file, though XD

Agreed. Wish they would just dynamically extract those files out of the exe. This defeats the entire purpose of single file.

What will be the future of Microsoft Store for apps after UWP converge into .NET 6 ?

What can developers expect?

Hi!

Regarding migration to System.Text.Json, I raised what I believe is a valid issue two weeks ago that has yet to merit a response. Is this something that you are planning on implementing? I had to switch back to Newtonsoft.Json for the time being.

https://github.com/dotnet/runtime/issues/593

Thank you!