The capabilities and constraints of the package management tool chain used by a particular ecosystem can have a dramatic impact on how you structure your repositories and whether you ship a single monolithic package, or whether you can break it up.

We’ve learned on the Azure SDK team that it generally works best if you start with the end-developer in mind and figure out how to optimize the consumption experience and then balance that against other considerations such as inner-loop developer efficiency, engineering system complexity, and supportability.

Back in March 2020 (seems so long ago doesn’t it!) we posted about how we structured the Azure SDK repositories. We compared some of the implications of mono-repo vs. micro-repo decisions when it comes to hosting our SDKs and outlined some of the key considerations for choosing between the two.

The quick version of that article is that we wanted to create a single place where developers and contributors could work together on a particular language or ecosystems version of the SDK. One of the factors in the decision was the level of tool chain support for our selected approach. For the most part we’ve managed to navigate the various trade-offs associated with choosing a mono-repository structure while still being able to ship various components of the SDK independently.

This is enabled in large part due to the fact that for many of our repositories (.NET, Java, JavaScript, and Python), the artifact we ship is a bundle of source/binaries which are consumed independently of where we host our source code. This means that its possible to have two libraries with interdependencies in the repo, but the dependent library can use the published version of the package whilst the new version continues to evolve (this is called binary composition – which the blog post linked above covers in a bit more detail).

But what about ecosystems where there is a significant relationship between the source repo and the method of consuming our SDK?

Package delivery systems

When developers consume third-party dependencies they need a way of hooking them into their builds at the right time. Really a package delivery system is just a convention that is agreed to by developers in a particular ecosystem which makes it easy to consume third-party code. In .NET for example, the unit of code reuse is an assembly (typically a DLL file), and a NuGet package is just a zip file containing that DLL for any target runtime versions that the package supports, as well as other metadata which describes that packages own dependencies. When you install the package it walks the graph of all dependencies and downloads each file in turn. The *.csproj file contains a list of packages that project depends on so that when you build it has somewhere to start looking for all the dependencies. Once all the DLL files are downloaded into the cache, the compiler is invoked with a pointer to these dependencies.

Each ecosystem does it slightly differently, but at the end of the day its about downloading source/binaries and hooking them into the build system for the project that a developer is working on.

Consuming via source

In ecosystems where there is no defacto standard for packaging, developers are left to come up with their own solutions for sharing code. In C, C++, and Objective-C codebases for example, it is not uncommon to see developers using Git sub-modules or committing entire snapshots of third party libraries.

Recently in the C++ community we’ve seen more efforts to formulate a standard approach to code-reuse. A good example is vcpkg. In the iOS community we see solutions like CocoaPods.

The general approach that these package managers take is that they allow you to express your dependencies and then the tooling takes care of pulling the appropriate version of the source and presenting it to your chosen build system for integration into your solution.

Source-based composition of dependencies is a common feature of ecosystems that produce native binaries where there tends to be less introspection capabilities at runtime.

Repository as package

Language/platform designers today can’t ignore the importance of having a simple and streamlined code reuse experience. It isn’t surprising then when we look at languages like Swift and Go that they have made early efforts to formalize what it means to create reusable code.

The difference with these ecosystems when compared to .NET, Java, JavaScript, and Python is that they’ve opted to strongly tie the definition of a package to the source repository that hosts it.

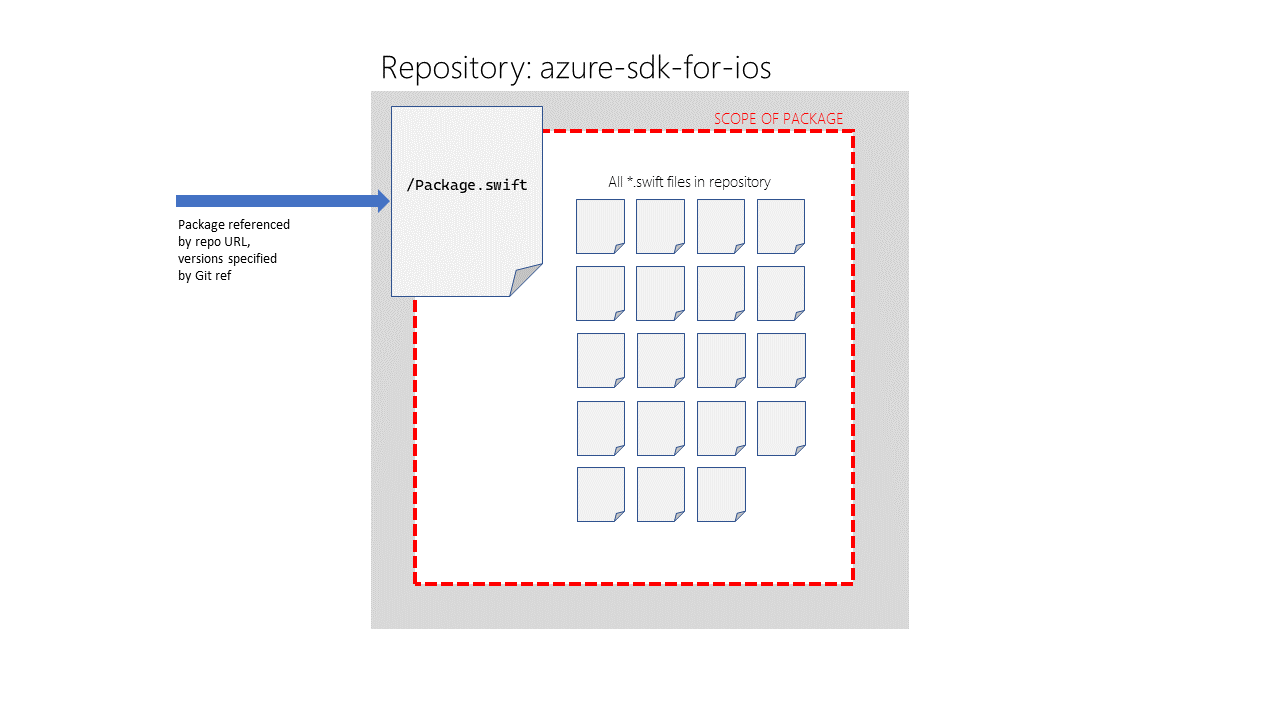

- Swift Package Manager looks for a

Package.swiftfile in the root of a Git repository and versions are targeted by Git ref.

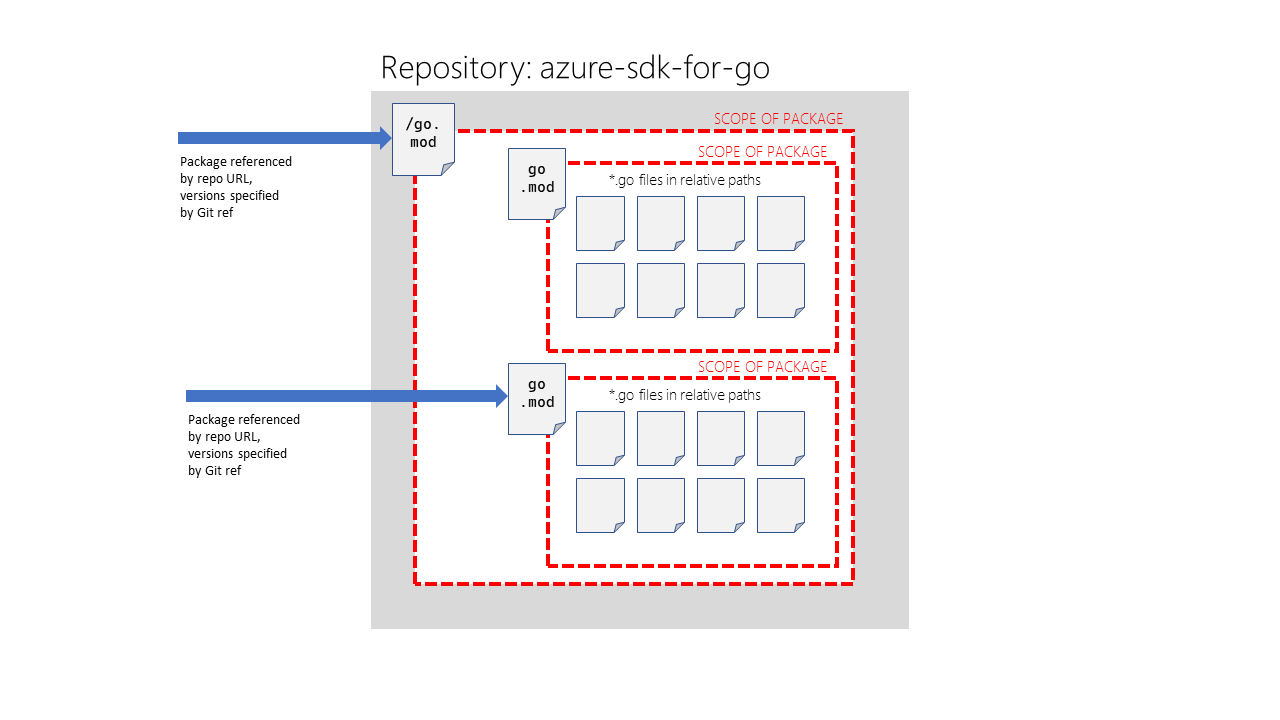

- Go uses a

Go.modfile to define a module and delcare its dependencies. Once again, the Git ref is used as the version specifier.

Repository as package has nice OSS characteristics

Source-based packages where the repository is used as a discovery and distribution mechanism makes it very easy for a consumer of your package to fork your repository on GitHub, make some local changes on a branch, and consume it within their own solution whilst they wait for their changes to be upstreamed (or not).

Downsides of repository as package

Like everything though there is a downside. In Swift specifically the model for repository as package is strictly one package per repository. This means that if you are tied to the monolithic repository model then you are going to have a monolithic package.

When building a set of APIs like we have in the SDK we need to carefully consider whether the requirement to ship the entire SDK at once vs. piecemeal is a blocker, and then depending on the packaging tool chain, that will have impacts on the way we structure our repositories.

In the case of our Swift SDKs we’ve opted to stick with the mono-repository approach to create a focal point for reporting issues and community contributions.

Go’s deep linking capability allows us to operate as a mono-repository but also ship module updates independently.

This is an example of where tool chain support has major implications for how you structure your repository and at what level of granularity you can release components to customers.

Use the tools that are idiomatic to the language and use them as intended

When it comes to building solutions I am a big proponent of the principle of least astonishment. Applied to the engineering systems for the Azure SDK, that means trying not the fight the tools that support the ecosystem that you are targeting.

For package managers this means understanding the relationship that package format, discovery, distribution, and cardinality have on the way that you structure your repository and the surrounding build and release systems.

The table below is a survey of some ecosystems and how they map to package format, discovery, distribution, and cardinality (whether the one repo can host sources for multiple packages):

| Ecosystem | Package format | Package discovery | Package distribution | Package cardinality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| .NET | Binary | Registry | Registry | 1:Many |

| Java | Binary | Registry | Registry | 1:Many |

| JavaScript | Source | Registry | Registry | 1:Many (1:1 by convention) |

| Python | Source1 | Registry1 | Registry1 | 1:Many |

| Swift | Source2 | Repository | Repository | 1:13 |

| Go | Source | Repository | Repository | 1:Many |

| Rust | Source | Registry | Registry | 1:Many (1:1 by convention) |

Notes

Python also supports binary distribution in the form of wheel packages, and source distribution can come directly from the version control system.

Swift Package Manager recently added support for wrapping binary frameworks (*.xcframework archives) in a package. The Swift Package metadata in the

Package.swiftfile still needs to be hosted in a repository, but the package itself can be a binary.Whilst Swift Packager Manager only supports one package per repository, a single package can define multiple Products which allow you to control which parts of the code is built.

With .NET for example, it is quite normal to have a single repository produce multiple packages because each package exists independently of the repository which contains its sources.

If we tried to do the same thing with Swift by comparison we’d frequently be fighting against the Swift tool chain.

In the JavaScript community, NPM packages are generally one package per repository, but the fact that package discovery and distribution is handled by the registry means that we can get away with breaking that convention in the interests of keeping a single place for developers to report issues and make contributions.

Conclusion

As we build out the SDK for each language/ecosystem we are constantly striving to maintain a balance of the productivity of the developers building the SDK and the experience of the developers consuming the SDK. The tool chains in each ecosystem influence much of how our engineering system works and the decisions we make about structuring and releasing the SDK.

Azure SDK Blog Contributions

Thank you for reading this Azure SDK blog post! We hope that you learned something new and welcome you to share this post. We are open to Azure SDK blog contributions. Please contact us at azsdkblog@microsoft.com with your topic and we’ll get you setup as a guest blogger.

- Azure SDK Website: aka.ms/azsdk

- Azure SDK Intro (3 minute video): aka.ms/azsdk/intro

- Azure SDK Intro Deck (PowerPoint deck): aka.ms/azsdk/intro/deck

- Azure SDK Releases: aka.ms/azsdk/releases

- Azure SDK Blog: aka.ms/azsdk/blog

- Azure SDK Twitter: twitter.com/AzureSDK

- Azure SDK Design Guidelines: aka.ms/azsdk/guide

- Azure SDKs & Tools: azure.microsoft.com/downloads

- Azure SDK Central Repository: github.com/azure/azure-sdk

- Azure SDK for .NET: github.com/azure/azure-sdk-for-net

- Azure SDK for Java: github.com/azure/azure-sdk-for-java

- Azure SDK for Python: github.com/azure/azure-sdk-for-python

- Azure SDK for JavaScript/TypeScript: github.com/azure/azure-sdk-for-js

- Azure SDK for Android: github.com/Azure/azure-sdk-for-android

- Azure SDK for iOS: github.com/Azure/azure-sdk-for-ios

- Azure SDK for Go: github.com/Azure/azure-sdk-for-go

- Azure SDK for C: github.com/Azure/azure-sdk-for-c

- Azure SDK for C++: github.com/Azure/azure-sdk-for-cpp

0 comments