AOT Compilation in HotSpot: Introduction

This blog post is not about SubstrateVM nor GraalVM but focuses on the jaotc AOT compiler in HotSpot.

Introduction

In this blog post, we are going to focus on the Ahead-Of-Time (AOT) Compilation that was introduced in Java 9 (https://openjdk.java.net/jeps/295) with the addition of the jaotc command-line utility. This AOT compiler is based on the work done in Graal JIT.

We are going to explore some of the tradeoffs that the AOT compiler needs to take, and how the generated code fits in the Tiered Compilation (TC) pipeline. Then, we will go through a simple example, showing how to use the jaotc command-line utility. Finally, we are going to explore some alternatives to the AOT compiler like JIT at Startup, JIT caching, and Distributed JIT.

AOT Compilation in HotSpot

An AOT compiler’s primary capability is to generate machine code for an application without having to run the application, allowing a future run of the application to pick the generated code. Similarly, to C1 and C2, jaotc compiles Java bytecode to native code.

The primary motivator behind using AOT in Java is to bypass the interpreter. It is generally faster for the machine to execute machine code than it is to execute the code via the bytecode interpreter. In many cases, it is a definite advantage, especially for code that needs to be executed even just a few times.

Tradeoffs of generated code

An AOT compiler cannot make the same class of assumptions as a JIT compiler. The AOT compiler doesn’t have access to as much information as the JIT compiler does because the process generating and executing the application are not the same.

For example, AOT compilers are required to generate Position Independent Code (PIC) to produce shared libraries. That is because there is no way to know ahead of execution where in memory the code is loaded, blocking any assumption the AOT compiler can make on the location (relative or absolute) of a symbol; this prevents the AOT compiler from referencing the address of any symbol directly. So, whenever a symbol (such as functions and constants) is accessed, it requires the AOT compiler to generate an indirection, with the resolution happening on first access to the symbol.

On the other hand, a JIT compiler can take the address in memory of a symbol and embed it directly in the code. It works because the JIT compiler can assume the code to have a shorter lifetime than the symbol: the code generation happens after the symbol initialization (or at least the code generation initializes the symbol), and the shutdown of the process triggers the destruction of both the code and the symbol.

Another example is final static variables. A JIT compiler can make certain assumptions allowing it to generate code based on the value of the variable. But because an AOT compiler cannot know the value of the variable before the initialization of the variable – which only happens at the execution of the code – it can’t make the same assumptions. That can lead to missed optimizations opportunities like dead-code elimination or inlining.

Finally, the OS and architecture on which you execute the code and on which you generate the code are required to be the same. For example, if you want to execute the code on Windows, you cannot generate the code on Linux or macOS but only on Windows. That is because the jaotc does not support cross-compilation.

Integration with the Tiered Compilation pipeline

Introduced in Java 7, Tiered Compilation (TC) goal is to have fast startup time and fast steady-state throughput. The implementation consists of a pipeline of multiple tiers of code generation. The three main components of this pipeline are the interpreter, the C1 compiler, and the C2 compiler. It replaced the -client and -server command-line parameters available in previous versions of Java.

As the method goes through the different tiers, each tier gathers information about the method execution. This information is called Profiling Data (PD). The C2 compiler uses this PD to make certain assumptions such as what code paths are cold/warm/hot, and what types are used at any call sites. It can then generate code better suited for the specific context that it is currently executing in.

The five tiers of code generation are:

- none (0): Interpreter gathering full PD

- simple (1): C1 compiler with no profiling

- limited profile (2): C1 compiler with light profiling gathering some PD

- full profile (3): C1 compiler with full profiling gathering full PD

- full optimization (4): C2 compiler with no profiling

With jaotc, you have the option to generate code with or without support for TC. Enabling TC generates slightly slower code due to the profiling overhead. Disabling TC blocks the use of the TC pipeline leading to slower steady-state throughput.

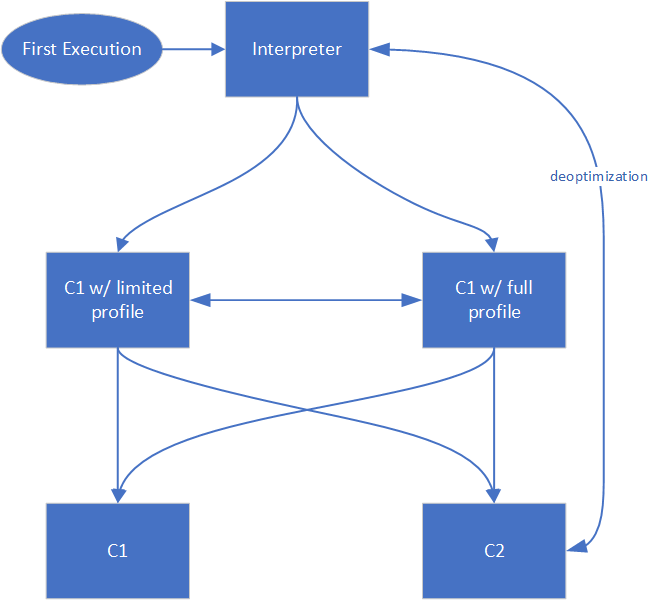

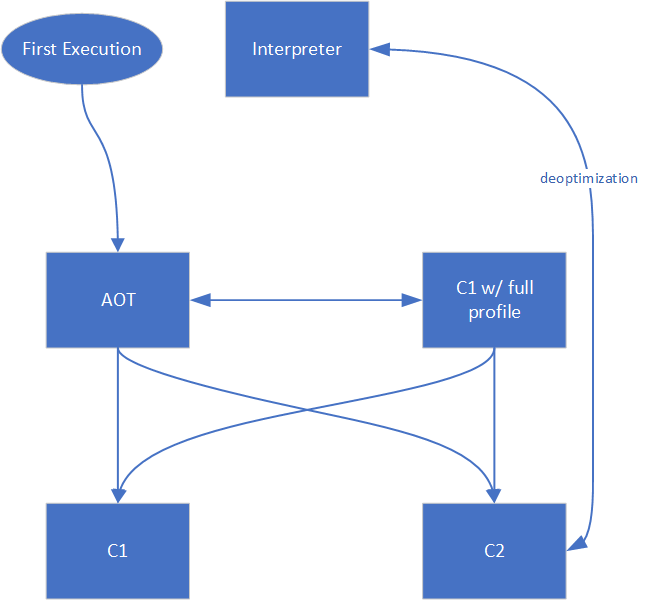

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the flow in the TC pipeline if you use AOT or not.

The difference in generated code by the AOT compiler with and without support for TC is trivial. For the TC pipeline to decide whether to compile the method at a particular tier, the generated code updates a set of counters (invocation counters, backedge counters) when executing, and whenever any of these counters overflow a given threshold, the instrumented code calls back into the runtime. This call contains all the information needed by the runtime to figure out which method has reached the threshold. It allows the runtime to decide whether to compile the method at the next tier of the TC pipeline. Given that, if you generate code that does not have support for TC, then the counters are never updated, thus never overflowed, and it never calls back into the runtime to request compilation at the next tier of the TC pipeline.

In case the code has been generated with support for TC, AOT code fits in the TC pipeline at roughly the same tier as the limited profile (2) tier. The threshold value differs, with, for example, the execution threshold to go from Tier 0 or Tier 2 to Tier 3: the default value without AOT is Tier3InvocationThreshold=200, and the default value with AOT is Tier3AOTInvocationThreshold=10000.

Usage

For the AOT compiler to successfully generate code, the same environment than for the JIT compiler need to be available. That means that all dependencies (jars, jmods) must be present and accessible to the AOT compiler.

The example below is assuming you are using Java 11 or later.

Let’s take a simple example, HelloWorld.

class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String args[]) {

System.out.println("Hello, World");

}

}

To compile it to Java bytecode, run the usual:

$> javac HelloWorld.java

If you want to run without AOT, you simply run:

$> java HelloWorld Hello, World

If you want to run with AOT, you first need to run the AOT compiler:

$> jaotc --compile-for-tiered --output libHelloWorld.so --verbose HelloWorld Compiling libHelloWorld.so... 1 classes found (25 ms) Scanning HelloWorld added <init>()V added main([Ljava/lang/String;)V 2 methods total, 2 methods to compile (4 ms) Freeing memory [used: 4.0 MB , comm: 12.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 66.7%] (44 ms) Compiling with 12 threads . 2 methods compiled, 0 methods failed (363 ms) Freeing memory [used: 5.4 MB , comm: 18.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 70.0%] (17 ms) Parsing compiled code (2 ms) Freeing memory [used: 5.8 MB , comm: 24.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 75.9%] (18 ms) Processing metadata (10 ms) Freeing memory [used: 5.7 MB , comm: 24.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 76.2%] (18 ms) Preparing stubs binary (0 ms) Preparing compiled binary (0 ms) .header: 63 bytes .config: 43 bytes .kls.offsets: 336 bytes .meth.offsets: 52 bytes .kls.dependencies: 76 bytes .stubs.offsets: 1036 bytes .meth.metadata: 7832 bytes .text: 17800 bytes .code.segments: 137 bytes .meth.constdata: 14344 bytes .kls.got: 224 bytes .cnt.got: 48 bytes .meta.got: 32 bytes .meth.state: 360 bytes .oop.got: 8 bytes .meta.names: 2234 bytes Freeing memory [used: 5.7 MB , comm: 24.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 76.2%] (18 ms) Creating binary: libHelloWorld.o (14 ms) Freeing memory [used: 5.7 MB , comm: 24.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 76.2%] (18 ms) Creating shared library: libHelloWorld.so (19 ms) Final memory [used: 5.6 MB , comm: 24.0 MB, freeRatio ~= 76.8%] Total time: 911 ms

Then to reference the code generated by the AOT compiler, run:

$> java -XX:AOTLibrary=./libHelloWorld.so HelloWorld Hello, World

To verify if the AOT compiled code is loaded and executed, run the above command with -XX:+PrintAOT and you should observe the following output:

$> java -XX:AOTLibrary=./libHelloWorld.so -XX:+PrintAOT HelloWorld 17 1 loaded ./libHelloWorld.so aot library 58 1 aot[ 1] HelloWorld.<init>()V 58 2 aot[ 1] HelloWorld.main([Ljava/lang/String;)V Hello, World

You can observe the output of -XX:PrintAOT in the first three lines. Line 1 signals that ./libHelloWorld.so was correctly loaded. Lines 2 and 3 signal that the constructor HelloWorld.<init>() and the main method HelloWorld.main() were loaded and used for this execution of the application.

Alternatives

Other approaches to code generation apart from AOT are in development in Java. Similarly, to AOT, some of them focus on startup throughput (JIT at Startup and JIT Caching), while others focus on compilation footprint (JIT out of Process).

JIT at Startup

At startup, before the Java main() method executes, the JVM compiles a predefined set of methods. The C2 compiler is used to compile these methods and, because both the generation and the execution of the code happen in the same process, the C2 compiler doesn’t require any modifications. PD is available alongside the predefined set of methods and is used to generate better code.

The procedure to determine the predefined set of methods is simple: previous runs gather this information, both by saving the compiled methods and the PD used to compile these methods.

This approach answers a very particular need: guaranteeing a high throughput from the get-go, at the expense of startup time.

Two implementations are Azul ReadyNow, available in Azul Zing, and JWarmup, available in Alibaba Dragonwell (currently a draft JEP in OpenJDK).

JIT Caching

During the execution of an application, the JVM dumps the code generated to disk. It allows the JVM, at the next execution of the application, to only have to pick-up where it left off, loading the code previously generated from disk, and have a robust startup throughput. It differs from the AOT compiler in the requirement to run the application to generate the code, while the AOT compiler only involves parsing the application’s code.

This method requires persistent storage between runs of the application. It does require the same dependencies and environment between runs. Otherwise, you cannot always guarantee that the code generated on a previous run is compatible with the current one.

Two implementations are OpenJ9 Dynamic AOT and Azul Compile Stashing, available in Azul Zing.

Distributed JIT

This method assumes that offloading the code generation to another process on another machine has a smaller footprint than generating the code in-process. It works particularly well in constrained environments (for example, less than 512 MB of RAM and half of a CPU core) where you can off-load the code generation to bigger machines, freeing precious resources for the application. Moreover, it allows for system-level optimizations by allowing better caching of the generated code across many runs of the same application (ex: running Hadoop across dozens, hundreds of machines).

The overall goal is not to reduce startup time or improve startup throughput – like AOT compilation, JIT at Startup, or JIT Caching – but to reduce the impact of the JIT compiler on the application footprint. That makes it a great complement to these other methods.

An implementation is OpenJ9 JITaaS.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we explored tradeoffs in the code generated by the AOT compiler (like Position Independent Code), and how the code fits in the TC pipeline. We also looked at other solutions in the Java ecosystem like JIT at Startup, JIT Caching and Distributed JIT, and how these solutions fit in the larger code generation aspect of the JVM.

In a future post, we’ll dig deeper into the implementation of jaotc and how the code is loaded and used by HotSpot.

Light

Light Dark

Dark

0 comments